Coordinates:  51.7500°N 0.3539°W

51.7500°N 0.3539°W

| Verulamium |

Remains of the city walls

|

|

Verulamium shown within Hertfordshire |

|

|

Verulamium was a town in Roman Britain. It was sited in the southwest of the modern city of St Albans in Hertfordshire, Great Britain. A large portion of the Roman city remains unexcavated, being now park and agricultural land, though much has been built upon (see below).[1] The ancient Watling Street passed through the city. Much of the site and its environs is now classed as a scheduled ancient monument.[2]

History

Before the Romans established their settlement, there was already a tribal centre in the area which belonged to the Catuvellauni. This settlement is usually called Verlamion. The etymology is uncertain but the name has been reconstructed as *Uerulāmion, which would have a meaning like “[the tribe or settlement] of the broad hand” (Uerulāmos) in Brittonic.[3] In this pre-Roman form, it was among the first places in Britain recorded by name. The settlement was established by Tasciovanus, who minted coins there.

The Roman settlement was granted the rank of municipium around AD 50, meaning its citizens had what were known as “Latin Rights”, a lesser citizenship status than a colonia possessed. It grew to a significant town, and as such received the attentions of Boudica of the Iceni in 61, when Verulamium was sacked and burnt on her orders: a black ash layer has been recorded by archaeologists, thus confirming the Roman written record. It grew steadily; by the early 3rd century, it covered an area of about 125 acres (0.51 km2), behind a deep ditch and wall. It is the location of the martyrdom of the first British martyr saint, Saint Alban, who was a Roman patrician converted by the priest Amphibalus.[4]

Verulamium contained a forum, basilica and a theatre, much of which were damaged during two fires, one in 155 and the other in around 250. One of the few extant Roman inscriptions in Britain is found on the remnants of the forum (see Verulamium Forum inscription). The town was rebuilt in stone rather than timber at least twice over the next 150 years. Occupation by the Romans ended between 400 and 450.

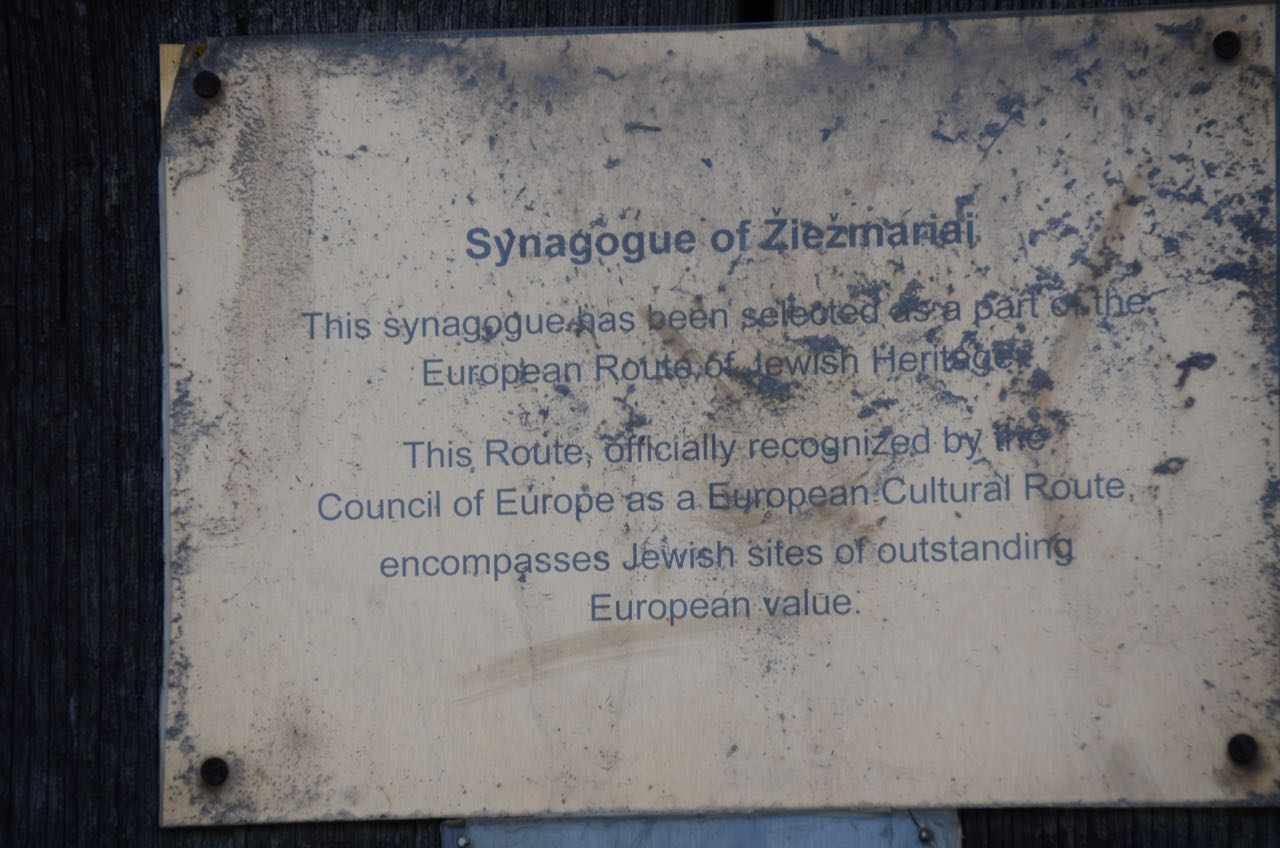

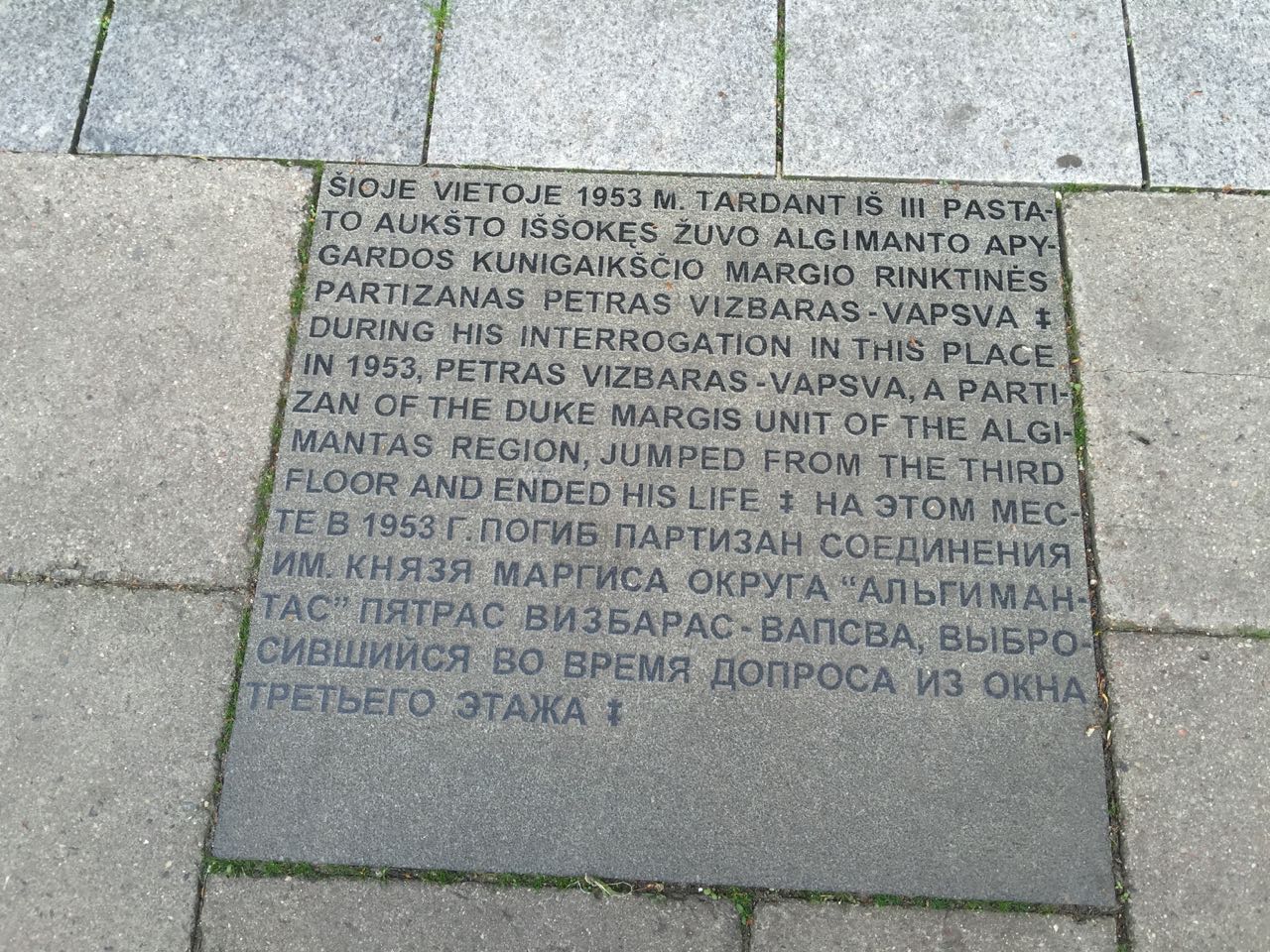

There are a few remains of the Roman city visible, such as parts of the city walls, a hypocaust still in situ under a mosaic floor, and the theatre, which is on land belonging to the Earl of Verulam, as well as items in the Museum (below). More remains under the nearby agricultural land which have never been excavated were for a while seriously threatened by deep ploughing.

Sub-Roman times

St Albans Abbey and the associated Anglo-Saxon settlement were founded on a hill outside the Roman city. The site of the abbey may have been a location where there was reason to believe that St Alban was executed or buried. More certainly, the abbey is near the site of a Roman cemetery, which, as was normal in Roman times, was outside the city walls. It is unknown whether there are Roman remains under the medieval abbey. An archaeological excavation in 1978, directed by Martin Biddle, failed to find Roman remains on the site of the medieval chapter house.[5]

David Nash Ford identifies the community as the Cair Mincip[6] (“Fort Municipium“) listed by Nennius among the 28 cities of Britain in his History of the Britains.[7] As late as the eighth century the Saxon inhabitants of St Albans nearby were aware of their ancient neighbour, which they knew alternatively as Verulamacæstir or, under what H. R. Loyn terms “their own hybrid”, Vaeclingscæstir, “the fortress of the followers of Wæcla”, possibly a pocket of British-speakers remaining separate in an increasingly Saxonised area.[8]

Loss and recovery

The city was quarried for building material for the construction of medieval St Albans; indeed, much of the Norman abbey was constructed from the remains of the Roman city, with Roman brick and stone visible. The modern city takes its name from Alban, either a citizen of Verulamium or a Roman soldier, who was condemned to death in the 3rd century for sheltering Amphibalus, a Christian. Alban was converted by him to Christianity, and by virtue of his death, Alban became the first British Christian martyr.

Since much of the modern city and its environs is built over Roman remains, it is still common to unearth Roman artefacts several miles away. A complete tile kiln was found in Park Street some six miles (10 km) from Verulamium in the 1970s, and there is a Roman mausoleum near Rothamsted Park five miles (8 km) away.

Within the walls of ancient Verulamium, the Elizabethan philosopher, essayist and statesman Sir Francis Bacon built a “refined small house” that was thoroughly described by the 17th century diarist John Aubrey. No trace of it is left, but Aubrey noted, “At Verulam is to be seen, in some few places, some remains of the wall of this Citie”.

Moreover, when Bacon was ennobled in 1618, he took the title Baron Verulam after Verulamium. The barony became extinct after he died without heirs in 1626.

This title was revived in 1790 for James Grimston, a Hertfordshire politician. He was later made Earl of Verulam, a title still held by his descendants.

Another stretch of Roman wall

Verulamium Museum

The Verulamium Museum is a sizeable museum run by the district council in Verulamium Park (adjacent to St Michael’s Church), which contains much information about the town, both as a Roman and Iron Age settlement, plus Roman history in general. The museum was established following the excavations carried out by Mortimer Wheeler and his wife, Tessa Wheeler, during the 1930s. It is noted for the large and colourful mosaics and many other artefacts, such as pottery, jewellery, tools and coins, from the Roman period. Many were found in formal excavations, but some, particularly a coffin still containing a male skeleton, were unearthed nearby during building work. It is considered one of the best museums of Roman history in the country and has won an architectural award for its striking domed entrance.