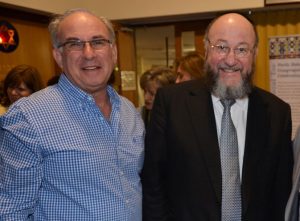

The Stropkover Rebbe has just completed a visit to Perth Australia from Jerusalem.

We were honoured to have him spend Shabbat with us at the CHABAD shul in Noranda WA.

He has visited Perth before.

I took the opportunity on Saturday night to learn more about him and his town.

The Rebbe was born in Germany and lives in Jerusalem. The Stropkover Rebbe’s “once upon a time” community was based in Stropkov in Slovakia.

Stropkov

| Stropkov | ||

| Town | ||

|

View of Stropkov

|

||

|

||

| Country | Slovakia | |

|---|---|---|

| Region | Prešov | |

| District | Stropkov | |

| River | Ondava | |

| Elevation | 202 m (663 ft) | |

| Coordinates | 49°12′18″N 21°39′05″ECoordinates: 49°12′18″N 21°39′05″E | |

| Area | 24.667 km2 (9.524 sq mi) | |

| Population | 10,866 (2012-12-31) | |

| Density | 441 / km2 (1,142 / sq mi) | |

| First mentioned | 1404 | |

Stropkov (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈstropkow]; Hungarian: Sztropkó, pronounced [ˈstropkoː], Yiddish: סטראפקאוו) is a town in Stropkov District, Prešov Region, Slovakia.

Jewish community

Jews first arrived in Stropkov, possibly fleeing Polish pogroms, in about 1650. About fifty years later, the Jews were exiled from Stropkov to Tisinec, a village just to the north. They did not return to Stropkov until about 1800. The Stropkov Jewish cemetery was dedicated in 1892, after which the Tisinec cemetery fell into disuse.

In 1939 the antisemitic Hlinka Party gain control of the Stropkov Town Council. From May–October 1942 the Hlinka deported Jews from the Stropkov area to Auschwitz, Sobibor, Maidanek, and “unknown destinations”. By the end of World War II, only 100 Jews remained in Stropkov out of 2000 in 1942.

Chief Rabbis of Stropkov

The first rabbi of Tisinec and Stropkov was Rabbi Moshe Schonfeld. He left Stropkov for a position in Vranov. He was succeeded in 1833 by Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Teitelbaum (I)(1818–1883) who served as Stropkov’s chief rabbi until leaving for a post in Ujhely. The next incumbent was Rabbi Chaim Yosef Gottlieb (1790–1867), known as the “Stropkover Rov”. He was succeeded by Rabbi Yechezkel Shraga Halberstam (1811–1899), a son of Rabbi Chaim Halberstam of Sanz. His scholarship, piety, and personal charisma transformed Stropkov into one of the most respected chasidic centers in all Galicia and Hungary. Rabbi Moshe Yosef Teitelbaum (1842–1897), the son of the aforementioned Rabbi Yekusiel Yehuda Teitelbaum, was appointed as Stropkov’s next chief rabbi in 1880.

The charismatic and scholarly Rabbi Yitzhak Hersh Amsel (c1855–1934), the son of Peretz Amsel of Stropkov, was first appointed as a dayan in Stropkov and then as the rabbi of Zborov (near Bardejov). As legend has it, Rabbi Yitzhak Hersh Amsel died while praying in his Zborov synagogue. He is buried in the Stropkov cemetery where a small protective building ohel was erected over his grave to preserve it. Rabbi Amsel was succeeded in 1897 by Rabbi Avraham Shalom Halberstam (1856–1940). Jews, learned and simple alike, sought the advice and blessing of this “miracle rabbi of Stropkov”, revered as a living link in the chain of Chassidus of Sanz and Sienawa. Rabbi Halberstam served in Stropkov for some forty years, until the early 1930s, when he assumed a rabbinical post in the larger town of Košice. Rabbi Menachem Mendel Halberstam (1873–1954),the son of the aforementioned Rabbi Avraham Shalom Halberstam was then appointed chief rabbi of Stropkov and head of the Talmud Torah. After World War II Rabbi Menachem Mendel Halberstam lived in New York until the end of his life, teaching at the Stropkover Yeshiva, which he founded in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

The present day Admor of Stropkov is HaRav Avraham Shalom Halberstam of Jerusalem. The Admor runs several yeshivas and kolelim in Jerusalem and other cities in Israel. The Admor dedicates himself to Ahavat Yisrael and to helping many who need to return to their Jewish roots.

I then went into my Geni account and looked up the Stropkover Rebbe and found what appeared to be his family line.

I recalled that on Shabbat, he had been called up to the torah as HaRav Avraham Shalom ben Yechezkel Shrage.

Havdalah after Shabbat.

On Sunday I printed out this page on Geni and showed it to the Rebbe who confirmed that this was indeed him – i.e. Avraham Shalom Lipschutz (Halberstam). He also confirmed that his mother was Beila, daughter of Avraham Shalom Halberstam.

I also printed out the Geni page which shows our relationship and presented a copy to the Rebbe.

So, besides all the friends he has Downunder, he now is happy to have added a 8th cousin in this isolated Jewish community!

We are both members of the Katzenellenbogen Rabbinic Tree.