Online Jewish genealogy resources to be focus of Jewish Genealogical Society talk on 23 May 2021

Online Jewish genealogy resources to be focus of Jewish Genealogical Society talk on 23 May 2021

Online Jewish genealogy resources to be focus of Jewish Genealogical Society talk on 23 May 2021

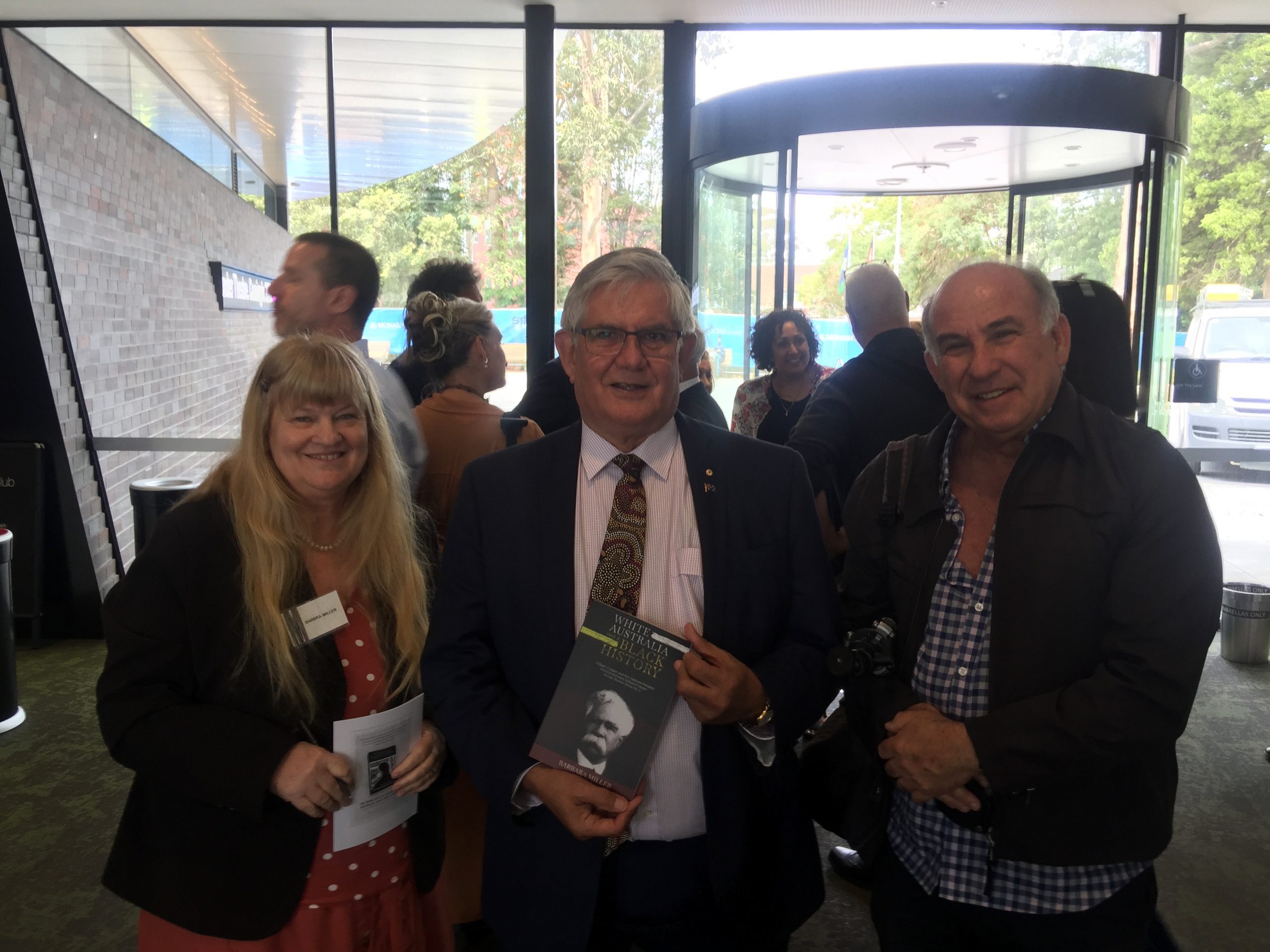

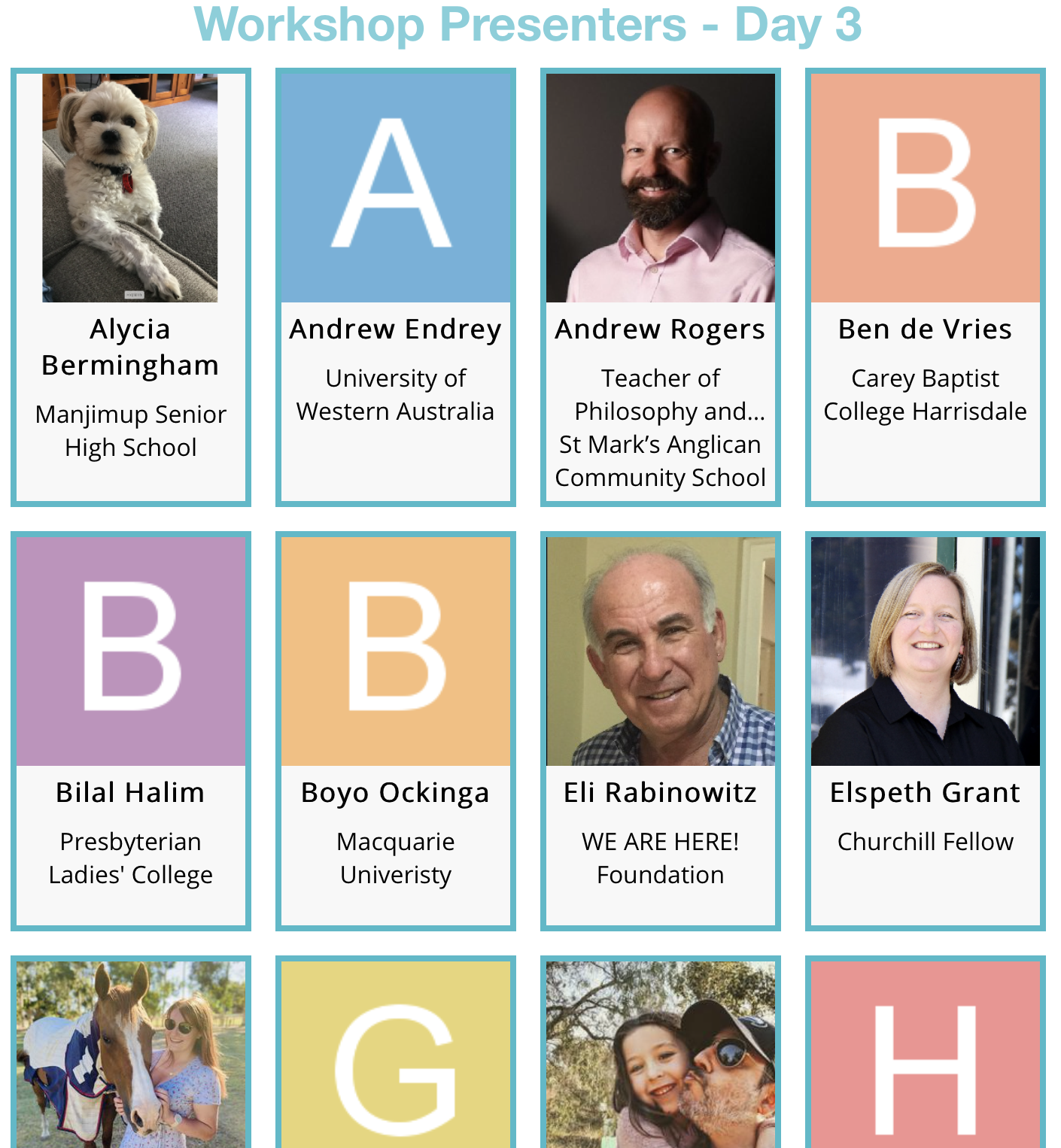

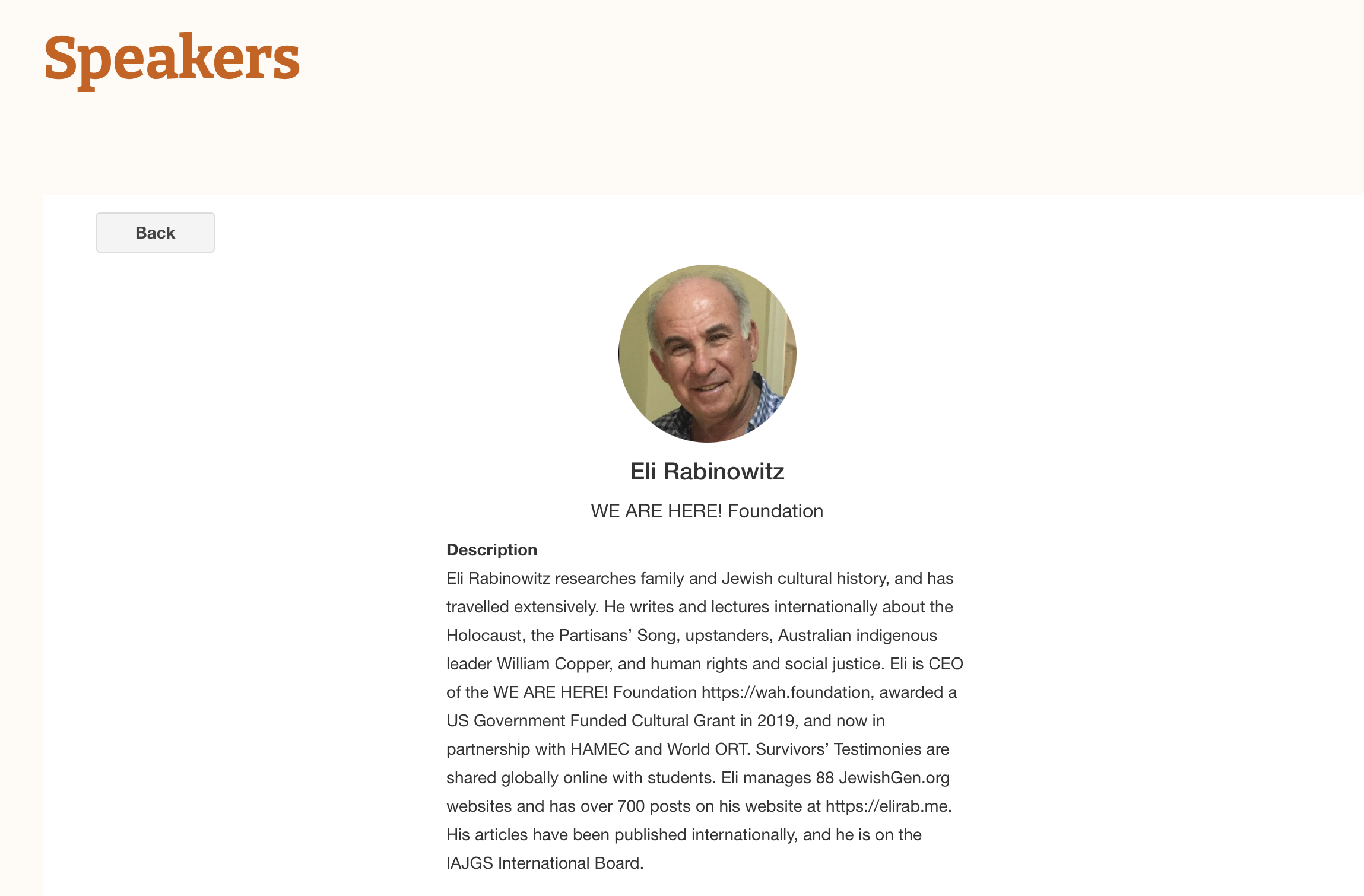

Eli Rabinowitz, a board member of the IAJGS who lives in Australia and is from South Africa, will speak on “Journeys from Shtetl to Shtetl” for the Sunday, 23 May 2021, virtual meeting of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Illinois. His live streaming presentation will begin at a special time: 7:30 pm CST.

8:30 pm ES 5:30 pm WST

Monday 24 May 2021: 10:30 am Sydney, 8:30 am Perth, 3:30 am Israel, 2:30 am South Africa, 1:30 am UK

Registration https://jgsi.org/event-3988686

After you register, you will be sent a link to join the meeting. This webinar will be recorded so that JGSI’s paid members who are unable to view it live will be able to view the recording later.

For more information, see https://jgsi.org or phone 312-666-0100.

In his presentation, Rabinowitz will explain how to trace our past and plot our future, using 88 KehilaLinks, over 800 WordPress blog entries, Facebook posts, and other social media. He will also discuss heritage travels in the actual and virtual worlds.

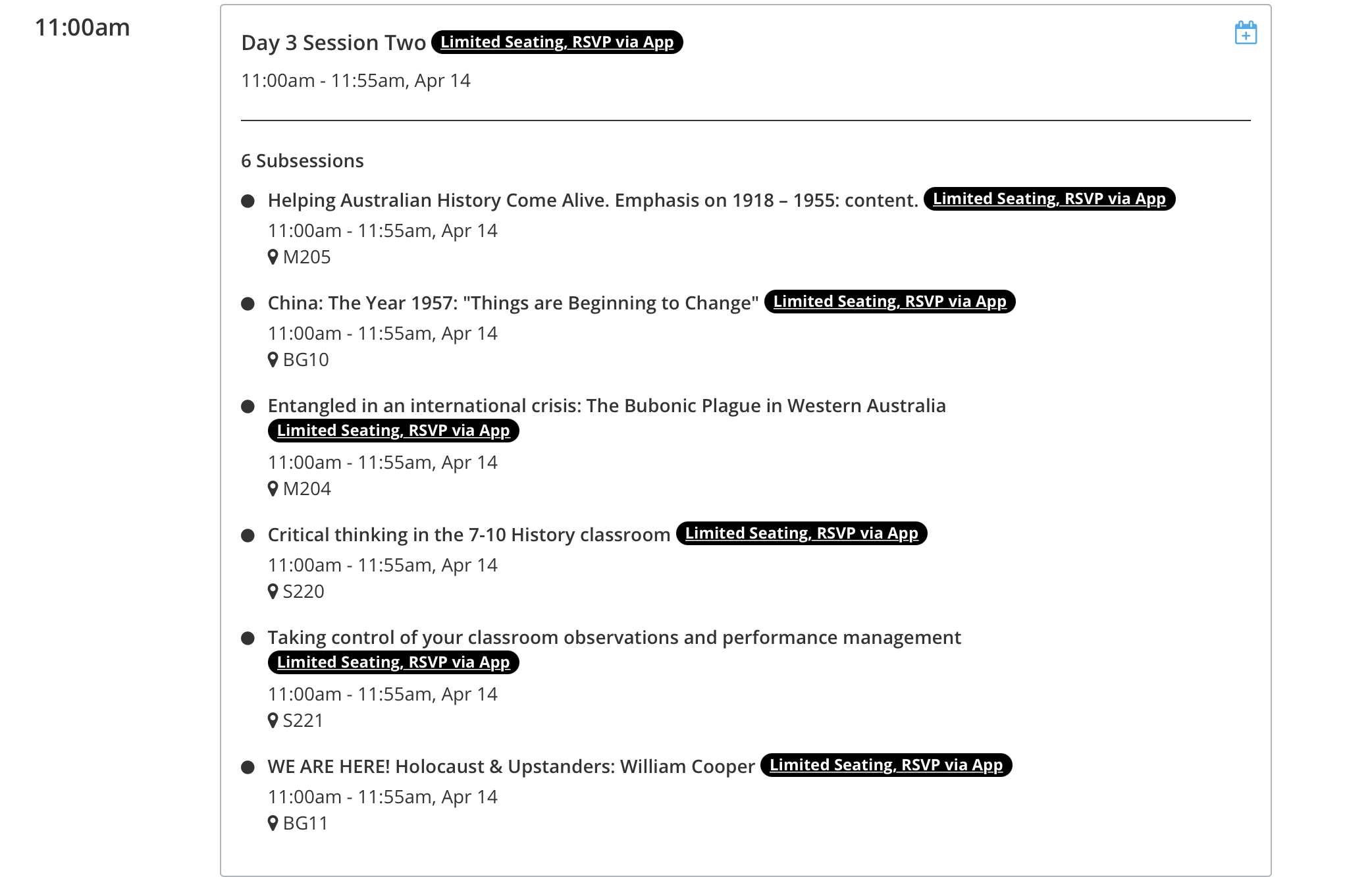

In his talk, Eli will describe special events including commemorations and reunions of descendants. “An important activity is to visit a local school—either physically or online, to engage with students, especially in towns where a few buildings with Jewish symbols, or cemeteries that often contain illegible matsevot, are the only tangible memories of a once thriving community,” he said.

It is also important that family histories should be documented and shared at the same time as the special events, Eli said.

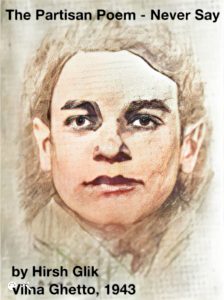

Examples of such recent ceremonies were the Bielski partisans’ descendants’ reunion in Naliboki and Navahrudak, Belarus; the new memorial for victims of the massacre that took place near Birzai, Lithuania; and the groundbreaking ceremony for the Lost Shtetl Museum in Šeduva, Lithuania.

Eli Rabinowitz was born in Cape Town, South Africa, and has lived in Perth, Australia, since 1986. He has researched his family’s genealogy and associated Jewish cultural history for over 30 years. Eli has travelled extensively, writing about Jewish life, travel, and education on his website, Tangential Travel and Jewish Life (http://elirab.me). He writes and manages dozens of JewishGen KehilaLinks and more than 750 WordPress blog posts. His articles have appeared in numerous publications, including Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy. Eli has lectured internationally at educational institutions, commemorative events, at IAJGS and other conferences, and online.

He is a board member of the IAJGS—The International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies, an independent non-profit umbrella organization that coordinates an annual conference of 84 Jewish genealogical societies worldwide.

Eli also advises on Litvak and Polish heritage tours.

He writes and manages 88 KehilaLinks—Jewish websites for JewishGen.org, the world’s largest Jewish genealogical organization, with a database of 500,000 followers. His KehilaLinks include sites in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Germany, Russia, China, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa and Australia.

The Jewish Genealogical Societyof Illinois is a non-profit organization dedicated to helping members collect, preserve, and perpetuate the records and history of their ancestors. JGSI is a resource for the worldwide Jewish community to research their Chicago-area roots. The JGSI motto is “Members Helping Members Since 1981.” The group has more than 300 members and is affiliated with the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies.

JGSI members have access to useful and informative online family history research resources, including a members’ forum, more than 65 video recordings of past speakers’ presentations, monthly JGSI E-News, quarterly Morasha JGSI newsletter, and much more. Members as well as non-members can look for their ancestors on the free searchable JGSI Jewish Chicago Database.

New Memorial Orla Poland 2021

The Ark, Melbourne

The Ark, Melbourne

William Cooper’s family, Richmond FC, Melbourne

William Cooper’s family, Richmond FC, Melbourne

Ralph Salinger & Michael Leiserowitz in Warsaw

Ralph Salinger & Michael Leiserowitz in Warsaw

Muizenberg SH, South Africa

Muizenberg SH, South Africa

On ‘The Chronicle’ page we list the Pretoria Jewish Chronicles from Diane Wolfson.

On ‘The Chronicle’ page we list the Pretoria Jewish Chronicles from Diane Wolfson.