16 July 2023

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9zZWFyY2g/cT1qb3N2YWluaWFpK2xpdGh1YW5pYSZzY2FfZXN2PTU1NjI0MTMyNCZybHo9MUM1Q0hGQV9lbkFVODg2QVU4OTMmc3hzcmY9QUI1c3RCaG5uRzhkVnNMNG1wWDZxTlVROTd6MndVNHZ1QSUzQTE2OTE4MjgyMTc3NzYmZWk9LVRfWFpQdjBMcHFjNC1FUGdkcXd3QTgmb3E9am9zdmFuYWkmZ3NfbHA9RWd4bmQzTXRkMmw2TFhObGNuQWlDR3B2YzNaaGJtRnBLZ0lJQURJSEVDTVlzQUlZSnpJSEVDTVlzQUlZSnpJSEVDNFlEUmlBQkRJSEVBQVlEUmlBQkRJR0VBQVlIaGdOTWdZUUFCZ2VHQTB5QmhBQUdCNFlEVElJRUFBWUhoZ05HQTh5QmhBQUdCNFlEVElHRUFBWUhoZ05TSU1yVUFCWTZoUndBSGdBa0FFQW1BR2RBcUFCd3c2cUFRTXlMVGk0QVFISUFRRDRBUUhDQWdnUUFCaUtCUmlSQXNJQ0VSQXVHSUFFR0xFREdJTUJHTWNCR05FRHdnSUVFQUFZQThJQ0RoQXVHSUFFR0xFREdNY0JHTkVEd2dJTEVDNFlpZ1VZc1FNWWd3SENBZ3NRTGhpQUJCaXhBeGlEQWNJQ0JCQWpHQ2ZDQWdzUUFCaUFCQml4QXhpREFjSUNCUkF1R0lBRXdnSU9FQzRZaWdVWXh3RVlyd0VZa1FMQ0FnY1FMaGlLQlJoRHdnSUZFQUFZZ0FUQ0FnY1FBQmlBQkJnS3dnSU5FQzRZZ0FRWXh3RVkwUU1ZQ3NJQ0J4QXVHSUFFR0FyQ0Fnc1FMaGlBQkJqSEFSaXZBY0lDRmhBdUdJQUVHQW9ZbHdVWTNBUVkzZ1FZNEFUWUFRSENBZzBRTGhnTkdJQUVHTWNCR0s4QndnSUpFQUFZRFJpQUJCZ0t3Z0lXRUM0WURSaUFCQmlYQlJqY0JCamVCQmpnQk5nQkFlSURCQmdBSUVHSUJnRzZCZ1lJQVJBQkdCUSZzY2xpZW50PWd3cy13aXotc2VycCIsImltYWdlX2lkIjotMSwiaW1hZ2VfdXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9pbWFnZXMvYnJhbmRpbmcvZ29vZ2xlZy8xeC9nb29nbGVnX3N0YW5kYXJkX2NvbG9yXzEyOGRwLnBuZyIsInRpdGxlIjoiSm9zdmFpbmlhaSBMaXRodWFuaWEgLSBHb29nbGUgU2VhcmNoIiwic3VtbWFyeSI6Ikpvc3ZhaW5pYWkgaXMgYSBzbWFsbCB0b3duIGluIEvEl2RhaW5pYWkgZGlzdHJpY3QsIGNlbnRyYWwgTGl0aHVhbmlhLiBJdCBpcyBsb2NhdGVkIG9uIHRoZSDFoHXFoXbElyBSaXZlciAxMCBrbSBzb3V0aHdlc3QgZnJvbSBLxJdkYWluaWFpLiIsInRlbXBsYXRlIjoidXNlX2RlZmF1bHRfZnJvbV9zZXR0aW5ncyJ9″]

With Laima Ardaviciene and Harry Gorfine

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9zZWFyY2g/cT1rZWRhaW5pYWkramV3aXNoK2NlbWV0cmV5JnJsej0xQzVDSEZBX2VuQVU4ODZBVTg5MyZvcT1rZWRhaW5pYWkrJmdzX2xjcnA9RWdaamFISnZiV1VxQmdnQUVFVVlPeklHQ0FBUVJSZzdNZ1lJQVJCRkdEa3lCZ2dDRUVVWVBESUdDQU1RUlJnOU1nWUlCQkJGR0QweUJnZ0ZFRVVZUVRJR0NBWVFSUmhCTWdZSUJ4QkZHRUhTQVFnMk9UVXhhakJxT2FnQ0FMQUNBQSZzb3VyY2VpZD1jaHJvbWUmaWU9VVRGLTgjcmxpbW09MTQ4MDM0MzMwNzgwMTU0OTAwOTIiLCJpbWFnZV9pZCI6LTEsImltYWdlX3VybCI6Imh0dHBzOi8vd3d3Lmdvb2dsZS5jb20vaW1hZ2VzL2JyYW5kaW5nL2dvb2dsZWcvMXgvZ29vZ2xlZ19zdGFuZGFyZF9jb2xvcl8xMjhkcC5wbmciLCJ0aXRsZSI6IktlZGFpbmlhaSBKZXdpc2ggQ2VtZXRlcnkgLSBHb29nbGUgU2VhcmNoIiwic3VtbWFyeSI6IkNFTUVURVJZOiBLZWRhaW5pYWkgaGFzIHR3byBKZXdpc2ggY2VtZXRlcmllcywganVzdCBvdXRzaWRlIHRvd24uIFRoZSBvbGQgb25lLCBmb3VuZGVkIGluIHRoZSAxOHRoIGNlbnR1cnksIHdhcyBkZXN0cm95ZWQsIGhhcyBubyBncmF2ZXN0b25lcyzigKYiLCJ0ZW1wbGF0ZSI6InVzZV9kZWZhdWx0X2Zyb21fc2V0dGluZ3MifQ==”]

Harry & Laima doing maintenance

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuaW55b3VycG9ja2V0LmNvbS9LZWRhaW5pYWkvZGF1a3NpYWlfNzU3NjRmIiwiaW1hZ2VfaWQiOi0xLCJpbWFnZV91cmwiOiJodHRwczovL3MuaW55b3VycG9ja2V0LmNvbS9nYWxsZXJ5LzI0MjQxNS5qcGciLCJ0aXRsZSI6IkRhdWvFoWlhaSIsInN1bW1hcnkiOiJPbiBUaHVyc2RheSBBdWd1c3QgMjgsIDE5NDEsIGEgZ3JvdXAgb2Ygb3ZlciAyLDAwMCBKZXdpc2ggbWVuLCB3b21lbiBhbmQgY2hpbGRyZW4gZnJvbSBLxJdkYWluaWFpIGFuZCB0aGUgbmVhcmJ5IHNldHRsZW1lbnRzIG9mIMWgxJd0YSBhbmQgxb1laW1pYWkgd2VyZSBtYXJjaGVkIHRvIHRoZSBoYW1sZXQgb2YgRGF1a8WhaWFpIGFwcHJveGltYXRlbHkgNWttIG5vcnRoIG9mIHRoZSB0b3duIGNlbnRyZSBhbmQgc2hvdCBpbiBzbWFsbCBiYXRjaGVzIGJ5IDIwIExpdGh1YW5pYW4gdm9sdW50ZWVycy4gVGhlIGNvcnBzZXMgd2UiLCJ0ZW1wbGF0ZSI6InVzZV9kZWZhdWx0X2Zyb21fc2V0dGluZ3MifQ==”]

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly9sb3N0c2h0ZXRsLmx0LyIsImltYWdlX2lkIjotMSwiaW1hZ2VfdXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly9sb3N0c2h0ZXRsLmx0L3VwbG9hZHMvc2hhcmVfaW1nX2VuXzEuanBnIiwidGl0bGUiOiJMb3N0IFNodGV0bCIsInN1bW1hcnkiOiJBIHdvcmxkLWNsYXNzIGluc3RpdHV0aW9uLCB0aGUgTG9zdCBTaHRldGwgTXVzZXVtLCB3aWxsIG9wZW4gaXRzIGRvb3JzIGluIMWgZWR1dmEgaW4gMjAyMy4g4oCcU2h0ZXRs4oCdIGlzIHRoZSBZaWRkaXNoIHdvcmQgZm9yIHNtYWxsIHRvd24sIGFuZCB0aGUgbmFtZSBMb3N0IFNodGV0bCBNdXNldW0gd2FzIGNob3NlbiB0byByZWZsZWN0IHRoZSBkaXNhcHBlYXJhbmNlIG9mIEpld2lzaCBjb21tdW5pdGllcyB0aGF0IHdlcmUgZGVzdHJveWVkIGR1cmluZyB0aGUgSG9sb2NhdXN0IGluIExpdGh1YW5pYSBhbmQgdGhyb3VnaG91dCBFYeKApiIsInRlbXBsYXRlIjoidXNlX2RlZmF1bHRfZnJvbV9zZXR0aW5ncyJ9″]

Update on opening of Lost Shetl: now in Summer 2024

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9zZWFyY2g/Z3Nfc3NwPWVKemo0dFRQMVRkSU55NUpMelpnOUdJclRrMHBMVXNFQURpbkJnQSZxPXNlZHV2YSZybHo9MUM1Q0hGQV9lbkFVODg2QVU4OTMmb3E9c2VkdXZhJmdzX2xjcnA9RWdaamFISnZiV1VxQ1FnQkVDNFlKeGlLQlRJTUNBQVFJeGduR09NQ0dJb0ZNZ2tJQVJBdUdDY1lpZ1V5QndnQ0VDNFlnQVF5QndnREVBQVlnQVF5REFnRUVBQVlGQmlIQWhpQUJESUdDQVVRUlJnOU1nWUlCaEJGR0QweUJnZ0hFRVVZUGRJQkNURXlNRFEzYWpCcU5LZ0NBTEFDQUEmc291cmNlaWQ9Y2hyb21lJmllPVVURi04IiwiaW1hZ2VfaWQiOi0xLCJpbWFnZV91cmwiOiJodHRwczovL3d3dy5nb29nbGUuY29tL2ltYWdlcy9icmFuZGluZy9nb29nbGVnLzF4L2dvb2dsZWdfc3RhbmRhcmRfY29sb3JfMTI4ZHAucG5nIiwidGl0bGUiOiJTZWR1dmEgLSBHb29nbGUgU2VhcmNoIiwic3VtbWFyeSI6IsWgZWR1dmEgaXMgYSB0b3duIGluIHRoZSBSYWR2aWxpxaFraXMgZGlzdHJpY3QgbXVuaWNpcGFsaXR5LCBMaXRodWFuaWEuIEl0IGlzIGxvY2F0ZWQgMTgga20gZWFzdCBvZiBSYWR2aWxpxaFraXMuXG7FoGVkdXZhIHdhcyBhbiBhZ3JpY3VsdHVyYWwgdG93biBkZWFsaW5nIGluIGNlcmVhbHMsIGZsYXggYW5kIGxpbnNlZWQsIHBpZ3MgYW5kIGdlZXNlIGFuZCBob3JzZXMsIGF0IHRoZSBzaXRlIG9mIGEgcm95YWwgZXN0YXRlIGFuZCBiZXNpZGUgYSByb2FkIGZyb20gS2F1bmFzIHRvIFJpZ2EuIFdpa2lwZWRpYSIsInRlbXBsYXRlIjoidXNlX2RlZmF1bHRfZnJvbV9zZXR0aW5ncyJ9″]

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9zZWFyY2g/cT13aW5kbWlsbCtyZXN0YXVyYW50K3NlZHV2YSZybHo9MUM1Q0hGQV9lbkFVODg2QVU4OTMmb3E9d2luZG1pbGwrcmVzdGF1cmFudCtzZWR1dmEmZ3NfbGNycD1FZ1pqYUhKdmJXVXlCZ2dBRUVVWU9USUhDQUVRQUJpQUJESUhDQUlRQUJpQUJESUhDQU1RQUJpQUJESU5DQVFRTGhpdkFSakhBUmlBQkRJSENBVVFBQmlBQkRJSENBWVFBQmlBQkRJTkNBY1FMaGl2QVJqSEFSaUFCRElIQ0FnUUFCaUFCRElIQ0FrUUFCaUFCTklCQ1RFMk1qTXhhakJxTktnQ0FMQUNBQSZzb3VyY2VpZD1jaHJvbWUmaWU9VVRGLTgiLCJpbWFnZV9pZCI6LTEsImltYWdlX3VybCI6Imh0dHBzOi8vd3d3Lmdvb2dsZS5jb20vaW1hZ2VzL2JyYW5kaW5nL2dvb2dsZWcvMXgvZ29vZ2xlZ19zdGFuZGFyZF9jb2xvcl8xMjhkcC5wbmciLCJ0aXRsZSI6IldpbmRtaWxsIFJlc3RhdXJhbnQgU2VkdXZhIC0gR29vZ2xlIFNlYXJjaCIsInN1bW1hcnkiOiJKZXdpc2ggc2V0dGxlcnMgaW4gTGl0aHVhbmlhIC0gU2VkdXZhLCBEYXJiZW5haSwgS2VkYWluaWFpLCBVa21lcmdlLCAuLi4gVGhlIHdvb2RlbiBtaWxsIGhhcyBidXJuZWQgZG93biwgYnV0IHRoZSBicmljayB3aW5kbWlsbCBidWlsdCBpbiBpdHMgcGxhY2Us4oCmIiwidGVtcGxhdGUiOiJ1c2VfZGVmYXVsdF9mcm9tX3NldHRpbmdzIn0=”]

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS9zZWFyY2g/Z3Nfc3NwPWVKemo0dExQMVRjd3lja3l5RXN6WVBRU3lDNUt6RTR0VnNqSkxNa29UY3pMVEFRQWpxUUtDUSZxPWtyYWtlcytsaXRodWFuaWEmcmx6PTFDNUNIRkFfZW5BVTg4NkFVODkzJm9xPWtyYWtlcytsaXRodWFuJmdzX2xjcnA9RWdaamFISnZiV1VxQndnQkVDNFlnQVF5Q2dnQUVBQVk0d0lZZ0FReUJ3Z0JFQzRZZ0FReUJnZ0NFRVVZT1RJSUNBTVFBQmdXR0I0eUJnZ0VFRVVZUWRJQkNURXdPRGs0YWpCcU9hZ0NBTEFDQUEmc291cmNlaWQ9Y2hyb21lJmllPVVURi04IiwiaW1hZ2VfaWQiOi0xLCJpbWFnZV91cmwiOiJodHRwczovL3d3dy5nb29nbGUuY29tL2ltYWdlcy9icmFuZGluZy9nb29nbGVnLzF4L2dvb2dsZWdfc3RhbmRhcmRfY29sb3JfMTI4ZHAucG5nIiwidGl0bGUiOiJLcmFrZXMgTGl0aHVhbmlhIC0gR29vZ2xlIFNlYXJjaCIsInN1bW1hcnkiOiJLcmFrZSwgS3Jha2VzLCBLcmFraXUsIEtyYWtpxbMsIEtyYWvEl3MsIEtyb2tpLCDQmtGA0LDQutC10YEgwrcgUG9wdWxhdGVkIHBsYWNlIC0gYSBjaXR5LCB0b3duLCB2aWxsYWdlLCBvciBvdGhlciBhZ2dsb21lcmF0aW9uIG9mIGJ1aWxkaW5ncyB3aGVyZSBwZW9wbGUgbGl2ZSBhbmQgd29yay4iLCJ0ZW1wbGF0ZSI6InVzZV9kZWZhdWx0X2Zyb21fc2V0dGluZ3MifQ==”]

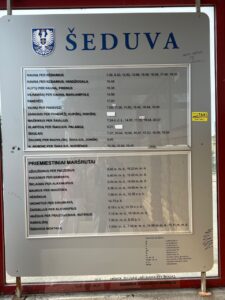

On the road to Krakes

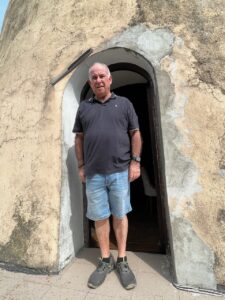

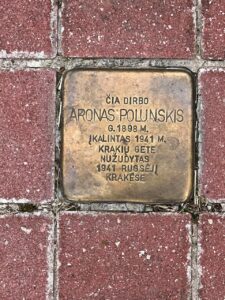

Krakes Cemetery

Meeting with Robertas Dubinka – Education Director and Daiva Dubinkienė, teacher.

Discussing In My Pocket Project.

https://elirab.au/project-update/

Back in Josvainiai for dinner