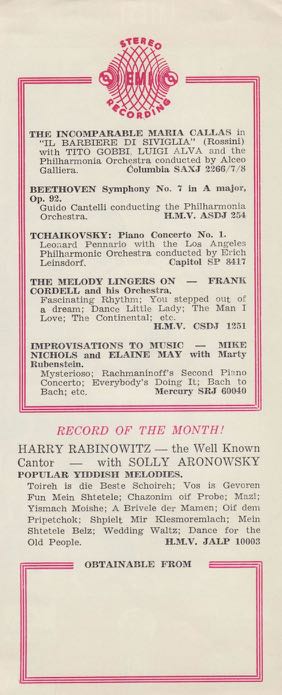

Richard Shavei-Tzion stands between his grandparents’ and his wife’s grandparents’ graves facing each other amongst tens of thousands in the Pinelands Cemetery, Cape Town

My family’s experience reflects the migratory patterns of South African Jewry, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the cemeteries of Cape Town. None of my great-great-grandparents is buried there, all having lived and died in Europe. Yet, with one exception, all of my great-grandparents and grandparents are laid to rest in these well-ordered cemeteries. They arrived between 1895 and 1916, three Litvak families and one from England, again a fair representation of South African Jewry’s roots.

The Jewish cemeteries in South Africa are for the most, lovingly maintained with the care that typifies Jewish communal life in the country. This is a community which thrives on an ethos of shared responsibility and mutual care. Despite its diminished number (now approximately 70,000 souls, down from 110,000 in the 1960’s) its institutions are thriving and the various burial societies are at the forefront of this phenomenon.

Unmarked children’s graves at Braamfontein Cemetery, Johannesburg

The Pinelands Cemetery in Cape Town has tens of thousands of graves. It is a well-ordered place with tombs marked by relatively standardized black upright stones. All of the graves appear on an online data base. A while ago, an American therapist friend asked if I could help her elderly South African client who had been distressed for years because she did not know her late mother’s Hebrew name. Within minutes I was able to provide her name and Yahrzeit and a photograph of the tombstone.

It is my custom to visit my ancestors’ tombstones once every few years when I travel to Cape Town from my home town of Jerusalem. Some years ago I went to visit my paternal grandparents Morris and Fanny Saevitzons’ graves. When I turned to leave, I was stunned by what I saw opposite. Call it cosmic chance, coincidence or “basheert”, but there, directly facing my grandparents’ tombstones, were the tombstones of Harry and Mina Lonstein, my wife’s maternal grandparents.

I mentioned that I have one ancestor who is not buried in Cape Town. Therein lies a story. I have been searching for this “missing” grave for a long time and with an impending trip to South Africa I thought I would try again. This time, between an intensive search of Internet sources and correspondence with the Johannesburg Chevra Kadisha, the self-styled “Chev”, we were able to locate the grave.

I happen to be an oldest son of an oldest son of an oldest son. My paternal great-grandfather, Abba Meir (Albert) Saevitzon together with his wife Chai Sarah and three sons arrived in Cape Town from Savlan, a small town in White Russia, in 1911. Their daughter was born within a few weeks of their arrival.

Almost immediately, Abba heard of a work opportunity in Johannesburg and the family travelled north, using all their remaining funds. Tragically, within a month he passed away and was buried in Johannesburg. The widowed, penniless Chai Sarah had no financial means with which to purchase a tombstone and was forced to leave the grave unmarked. She and her children returned to Cape Town with donated funds, where the older boys were sent to foster homes.

My grandfather, Morris, aged 14, lived in such a home and spent his days working at a local fishing harbor, cleaning fish as they came off the fishing boats, then carting them to the local fish market. He later became a fisherman and then worked in his father-in-law’s delicatessen store in the suburb of Wynberg, the heart of Cape Town’s Jewish community at that time. My aunt and uncle recall that as kids they hardly saw their father because he was working so hard to ensure that they would be well educated. You can see where his motivation came from. When I think of the “problems” we face in our day-to-day lives compared to those of my ancestors, I am chastened.

Yet even as the destitute family slowly began to establish itself, they did not forget their loved one’s burial place. So it was that a number of years after Abba’s passing, using the first of their savings, the family travelled for two days by train back to Johannesburg, purchased a tombstone and consecrated it.

On a typically cool but cloudless Johannesburg winter day I set out for the Westpark Cemetery, where Jews have been buried since around 1945. From there I was kindlyaccompanied by Mr. Braam Shevel who works at the Chev, to the Braamfontein Cemetery in what is now a very grungy area of the city.

Johannesburg was formally established in 1886 with the discovery of gold in the area and when the first Jew died there in 1887, a delegation of leaders of the emerging Jewish community travelled, one would imagine by horse or ox-wagon, to Pretoria to petition Paul Kruger for land for a Jewish cemetery. Kruger, president of the break-away South African Republic, and later the leader of the Boers in the Anglo-Boer War, acceded to their request and the first of approximately 90,000 Jewish graves in Johannesburg to date was dug there in Braamfontein.

Richard Shavei-Tzion at the grave of his great-grandfather at Braamfontein Cemetery, Johannesburg

Braam unlocked the heavy iron gate at the entrance to the cemetery, signaled me to drive in and locked the gate behind us. I was surprised by my feeling of peace and tranquility in this place despite its uncertain surroundings. The cemetery, shaded by tall, aged eucalyptus trees, is well maintained despite its age. As we searched for the stone, we passed tombs of the founders of the community and its institutions, mayors and mining magnates, famous personalities and the regular men and women who were drawn to the fledgling metropolis. Striking were the ages of people who died just one hundred years ago. By my very rough calculation, the average life span of the adults was no more than fifty years. Then there were the rows of children’s and infants’ graves, stark evidence of the rates of child mortality and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19.

And then from a little way off I spotted the name SAEVITZON and approached the stone, with an inexplicable sense of thanksgiving and reverence. It was in remarkable condition and I discovered that Abba Saevitzon died on the second day of Succot, having lived 37 years. Who knows when the name Abba first appeared in the family, but my father and his cousin were named after him and a number of my nephews and grandsons are named in my father’s memory so the tradition lives on.

Looking around, I noticed many unmarked graves, some whose names were unknown; others whose names were not marked for similar financial reasons and I was humbled by this act of care, sacrifice and loving kindness on the part of my ancestors.

I placed four stones on the grave, one for each of his children’s families,and turned to go.

Source: Esra Magazine

Chai Sarah Meyerowitz Saevitzon’s tombstone in Cape Town. Very indisctinct but some of the wording can be deciphered as you zoom in.

Richard Shavei Tzion

Cape Town born Richard Shavei-Tzion is an autodidact in all his fields of creative activity. At age 18 he was invited to conduct the Pine Street Shul Choir in Johannesburg. Since then he has directed choral ensembles in both South Africa and Israel. For the past 20 years he has directed the Ramatayim Men’s Choir, Jerusalem which has grown from an ad hoc group of 4 friends into an internationally renowned ensemble consisting of 40 singers. He has conducted High Holidays services for the past 35 years in South Africa, Israel, the U.S.A. and Canada and is often invited to lead communal events, singing and playing guitar. He also composes and arranges Jewish music, mainly for the RMC.