The Polin Museum

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

| Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich | |

The museum building

|

|

| Established | 2005 (opened April 2013) |

|---|---|

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Coordinates | 52°14′58″N 20°59′34″E |

| Type | Historical, cultural |

| Collection size | History and culture of Polish Jews |

| Visitors | expected 450,000 |

| Director | Dariusz Stola |

| Curator | Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett |

| Website | Museum official website |

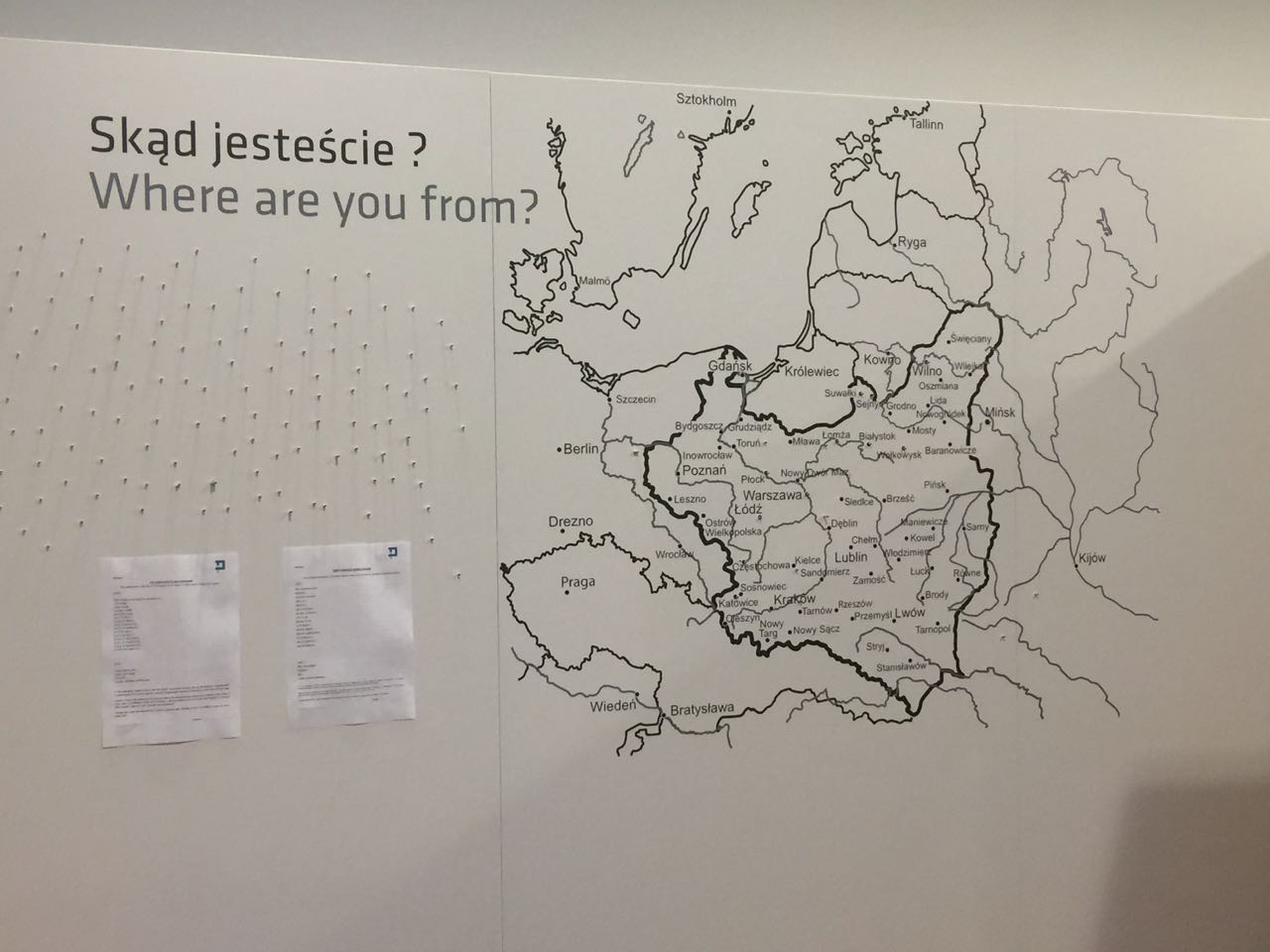

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Polish: Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich) is a museum on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. The Hebrew word Polin in the museum’s name means, in English, either “Poland” or “rest here” and is related to a legend on the arrival of the first Jews in Poland.[1] The cornerstone was laid in 2007, and the museum was first opened on April 19, 2013.[2][3] The museum’s Core Exhibition opened in October 2014.[4] The museum features a multimedia narrative exhibition about the vibrant Jewish community that flourished in Poland for a thousand years up to the Holocaust.[5] The building, a postmodern structure in glass, copper, and concrete, was designed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma.[6

History

President of the Republic of Poland, Lech Kaczynski, at the groundbreaking ceremony for the POLIN Museum, 26 June 2007

The idea for creating a major new museum in Warsaw dedicated to the history of Polish Jews was initiated in 1995 by the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland.[7] In the same year, the Warsaw City Council allocated the land for this purpose in Muranów, Warsaw’s prewar Jewish neighborhood and site of the former Warsaw Ghetto, facing the Monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Heroes. In 2005, the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland established a unique private-public partnership with the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the City of Warsaw. The Museum’s first director was Jerzy Halbersztadt. In September 2006, a specially designed tent called Ohel (the Hebrew word for tent in English) was erected for exhibitions and events on the museum’s future location.[7]

An international architectural competition for designs for the building was launched in 2005, supported by a grant from the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. On June 30, 2005 the jury announced the winner; a team of two Finnish architects, Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma.[8] On June 30, 2009 construction of the building was officially inaugurated. The project was to be finished in 33 months at a cost of PLN 150 million zlotyallocated by the Ministry and the City.[9] and a total cost of PLN 320 million zloty.[10][11]

The museum opened the building and began its educational and cultural programs on April 19, 2013 on the 70th Anniversary of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. During the 18 months that followed, more than 180,000 visitors toured the building, visited the first temporary exhibitions, and took part in cultural and educational programs and events, including films, debates, workshops, performances, concerts and lectures. The Grand Opening, with the completed Core Exhibition, was on October 28, 2014.[12] The Core Exhibition documents and celebrates the thousand-year history of the Jewish community in Poland that was decimated by the Holocaust.[4][5]

In 2016 the museum won the European Museum of the Year Award from the European Museum Forum.[13]

The Jewish Historical Institute

Three videos from Matan Shefi, whom I bumped in the street, not far from Polin

Jewish Historical Institute

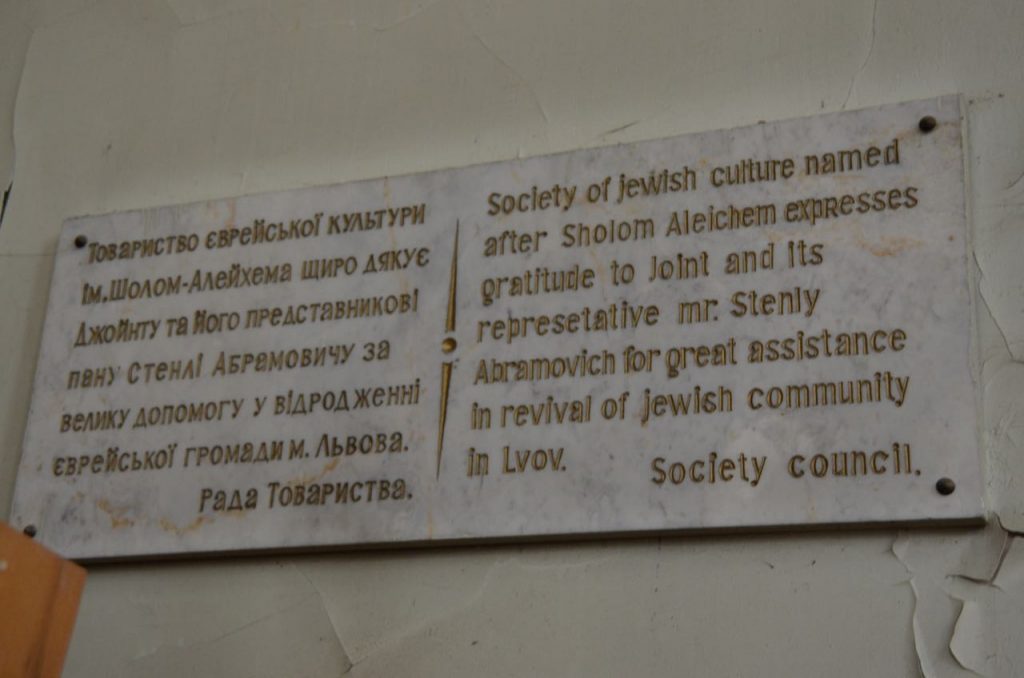

The Jewish Historical Institute (Polish: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny or ŻIH) is a research institute in Warsaw, Poland, primarily dealing with the history of Jews in Poland.

History

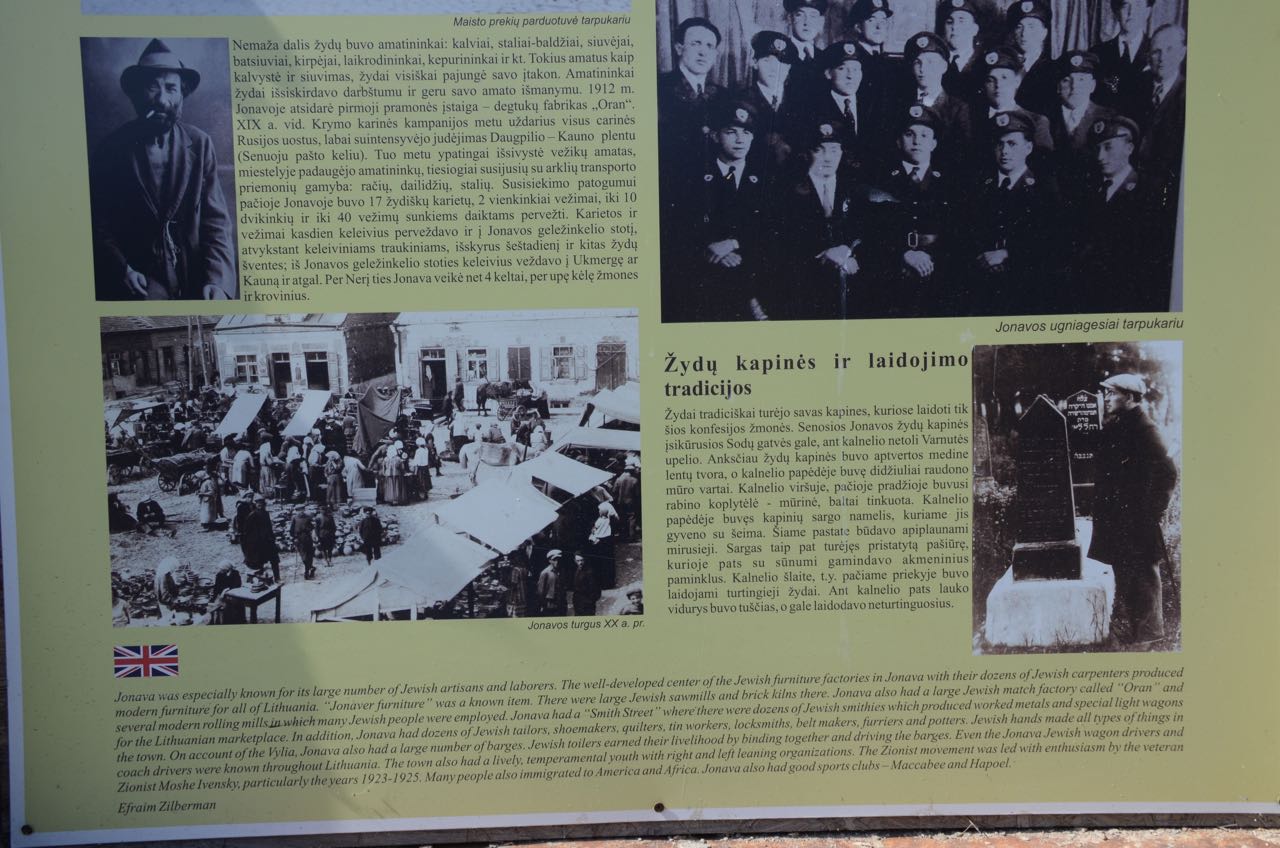

The Jewish Historical Institute was created in 1947 as a continuation of the Central Jewish Historical Commission, founded in 1944. The Jewish Historical Institute Association is the corporate body responsible for the building and the Institute’s holdings. The Institute falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. In 2009 it was named after Emanuel Ringelblum. The institute is a repository of documentary materials relating to the Jewish historical presence in Poland. It is also a centre for academic research, study and the dissemination of knowledge about the history and culture of Polish Jewry.

The most valuable part of the collection is the Warsaw Ghetto Archive, known as the Ringelblum Archive (collected by the Oyneg Shabbos). It contains about 6000 documents (about 30 000 individual pieces of paper).

Other important collections concerning World War II include testimonies (mainly of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust), memoirs and diaries, documentation of the Joint and Jewish Self-Help (welfare organizations active in Poland under the occupation), and documents from the Jewish Councils (Judenräte)

The section on the documentation of Jewish historical sites holds about 40 thousand photographs concerning Jewish life and culture in Poland.

The Institute has published a series of documents from the Ringelblum Archive, as well as numerous wartime memoirs and diaries.[1]

In 2011, Paweł Śpiewak, a Professor of Sociology at Warsaw University and former politician, was nominated as the Director of the Jewish Historical Institute by Bogdan Zdrojewski, Minister of Culture and National Heritage.[2]

The Nosyk Synagogue

Nożyk Synagogue

| Nożyk Synagogue Synagoga Nożyków |

|

|---|---|

| Basic information | |

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Geographic coordinates | 52°14′10″N 21°00′04″ECoordinates: 52°14′10″N 21°00′04″E |

| Affiliation | Orthodox Judaism |

| District | Śródmieście |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Active Synagogue |

| Leadership | Rabbi Michael Schudrich |

| Website | http://www.warszawa.jewish.org.pl |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Karol Kozłowski |

| Architectural style | neoromanesque |

| Completed | 1902 |

| Construction cost | 250.000 rubles |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 600 |

Interior of the synagogue

The Nożyk Synagogue (Polish: Synagoga Nożyków) is the only surviving prewar Jewish house of prayer in Warsaw, Poland. It was built in 1898-1902 and was restored after World War II. It is still operational and currently houses the Warsaw Jewish Commune, as well as other Jewish organizations.

History

Before World War II the Jewish community of Warsaw, one of the largest Jewish communities in the world at that time, had over 400 houses of prayer at its disposal. However, at the end of 19th century only two of them were separate structures, while the rest were smaller chapels attached to schools, hospitals or private homes. The earliest Round Synagogue in the borough of Praga served the local community since 1839, while the Great Synagogue (erected in 1878) was built for the reformed community. Soon afterwards a need arose to build a temple also for the orthodox Jewry. Between 1898 and 1902 Zalman Nożyk, a renowned Warsaw merchant, and his wife Ryfka financed such temple at Twarda street, next to the neighbourhood of Grzybów and Plac Grzybowski. The building was designed by a famous Warsaw architect, Karol Kozłowski, author of the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra Hall.[1] The façade is neo-romanticist, with notable neo-Byzantine elements. The building itself is rectangular, with the internal chamber divided into three aisles.

The synagogue was officially opened to the public on May 26, 1902. In 1914 the founders donated it to the Warsaw Jewish Commune, in exchange for yearly prayers in their intention. In 1923 the building was refurbished by Maurycy Grodzieński, who also designed a semi-circular choir that was attached to the eastern wall of the temple. In September 1939 the synagogue was damaged during an air raid. During World War II the area was part of the Small Ghetto and shared its fate during the Ghetto Uprising and then the liquidation of the Jewish community of Warsaw by the Nazis. After 1941 the Germans used the building as stables and a depot. After the war the demolished building was partially restored and returned to the Warsaw Jewish Commune, but the reconstruction did not start. It was completely rebuilt between 1977 and 1983 (officially opened April 18, 1983). It was also then that a new wing was added to the eastern wall, currently housing the seat of the commune, as well as several other Jewish organizations.

Ghetto Wall Marking

Meetings

Chopin and Kopernicus

The Storm

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Polish: Grób Nieznanego Żołnierza) is a monument in Warsaw, Poland, dedicated to the unknown soldiers who have given their lives for Poland. It is one of many such national tombs of unknowns that were erected after World War I, and the most important such monument in Poland.[1]

The monument, located at Piłsudski Square, is the only surviving part of the Saxon Palace that occupied the spot until World War II. Since 2 November 1925 the tomb houses an unidentified body of a young soldier who fell during the Defence of Lwów. At a later date earth from numerous battlefields where Polish soldiers have fought was added to the urns housed in the surviving pillars of the Saxon Palace.

The Tomb is constantly lit by an eternal flame and assisted by a guard post by the Representative Battalion of the Polish Army. It is there that most official military commemorations take place in Poland and where foreign representatives lay wreaths when visiting Poland.

The changing of the guard takes place on the hour of every hour daily and this happens 365 days a year.

History

In 1923, a group of unknown Varsovians placed, before Warsaw’s Saxon Palace and the adjacent Saxon Garden, a stone tablet commemorating all the unknown Polish soldiers who had fallen in World War I and the subsequent Polish-Soviet War. This initiative was taken up by several Warsaw newspapers and by General Władysław Sikorski. On April 4, 1925, the Polish Ministry of War selected a battlefield from which the ashes of an unknown soldier would be brought to Warsaw. Of some 40 battles, that for Lwów was chosen. In October 1925, at Lwów’s Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów, three coffins were exhumed: those of an unknown sergeant, corporal and private. The coffin that was to be transported to Warsaw was chosen by Jadwiga Zarugiewiczowa, mother of a soldier who had fallen at Zadwórze and whose body had never been found.

On November 2, 1925, the coffin was brought to Warsaw’s St. John’s Cathedral, where a Mass was held. Afterward eight recipients of the order of Virtuti Militari bore the coffin to its final resting place beneath the colonnade joining the two wings of the Saxon Palace. The coffin was buried along with 14 urns containing soil from as many battlegrounds, a Virtuti Militari medal, and a memorial tablet. Since then, except under German occupation during World War II, an honor guard has continuously been held before the Tomb.

Architecture

The Tomb was designed by the famous Polish sculptor, Stanisław Kazimierz Ostrowski. It was located within the arcade that linked the two symmetric wings of the Saxon Palace, then the seat of the Polish Ministry of War. The central tablet was ringed by 5 eternal flames and 4 stone tablets bearing the names and dates of battles in which Polish soldiers had fought during World War I and the Polish–Soviet War (1919–21). Behind the Tomb were two steel gratings bearing emblems of Poland’s two highest Polish military decorations — the Virtuti Militari and Cross of Valor.

During the 1939 invasion of Poland, the building was slightly damaged by German aerial bombing, but it was quickly rebuilt and seized by the German authorities. After the Warsaw Uprising, in December 1944, the palace was completely demolished by the Wehrmacht. Only part of the central colonnade, sheltering the Tomb, was preserved.

After the war, in late 1945, reconstruction began. Only a small part of the palace, containing the Tomb, was restored by Henryk Grunwald. On 8 May 1946 it was opened to the public. Soil from 24 additional battlegrounds was added to the urns, as well as more tablets with names of battles in which Poles had fought in World War II. However, the communist authorities erased all trace of the Polish–Soviet War of 1920, and only a few of the Polish Armed Forces’ battles in the West were included. This was corrected in 1990, after Poland had regained its political autonomy.

There are plans to rebuild the Saxon Palace, but as of May 2016, these plans have been indefinitely on hold due to a lack of budget.[citation needed]

The Hotel Bristol

Hotel Bristol, Warsaw

| Hotel Bristol, Warsaw | |

|---|---|

Hotel Bristol, Warsaw (2011)

|

|

| General information | |

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Address | Krakowskie Przedmiescie 42/44 |

| Opening | November 19, 1901 |

| Owner | Towarzystwo Akcyjne Budowy i Prowadzenia Hotelów, (1901-1928), Bank Cukrownictwa (1928-1948), City of Warsaw (1947-1952), Orbis (1952-1977), University of Warsaw (1977-1981), Orbis (1981-2011), Rosmarinum Investments (2011-) |

| Management | Starwood Hotels |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Władysław Marconi |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 168 |

| Number of suites | 38 |

| Website | |

| www.hotelbristolwarsaw.pl | |

Hotel Bristol, Warsaw is a historic luxury hotel opened in 1901 located on Krakowskie Przedmieście in Poland‘s capital, Warsaw

History

The Hotel Bristol was constructed from 1899-1900 on the site of the Tarnowski Palace by a company whose partners included Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski. A competition was held for the design of the building, and architects Thaddeus Stryjeriski and Franciszek Mączyński won with their Art Nouveau design. However the builders decided to change the style to a Neo-Renaissance design, and brought in architect Władysław Marconi to design the final hotel. Some of its interiors were designed by the noted Viennese architect Otto Wagner. The cornerstone was laid on April 22, 1899 and the hotel was dedicated on November 17, 1901 and opened on November 19, 1901.

Elegant cafe in the Bristol designed by Otto Wagner, 1901

After Poland gained its independence in 1919, Paderewski became the Prime Minister and held the first session of his government at his hotel. Paderewski and his partners sold their shares in the hotel in 1928 to a local bank, which renovated the hotel in 1934 with modern interiors by designer Antoni Jawornicki.

Upon the German invasion in 1939, the hotel was made into the headquarters of the Chief of the Warsaw District. It miraculously survived the war relatively unscathed, standing nearly alone among the rubble of its neighborhood. Following the war, the hotel was renovated and reopened in 1945.

The City of Warsaw took over operation of the hotel in 1947 and it was nationalized in 1948 and joined the state-run Orbis chain in 1952, exclusively serving visitors from abroad. By the 1970s its outdated facilities had seen it demoted to a second class ranking by the government and the hotel was donated by Prime Minister Peter Jaroszewicz to the University of Warsaw in 1977 to eventually serve as their library. It closed in 1981. However no work was done and the building languished through the waning days of the Communist government.

After the fall of Communism in 1989, the hotel was finally completely restored it to its former glory from 1991-1993, with the original interiors of the public rooms recreated to match the 1901 designs. The Bristol was reopened on April 17, 1993, with Margaret Thatcherin attendance, as part of the British Forte Hotels chain. From 1998 to 2013, the hotel was part of the Le Méridien hotel chain. The exterior was further restored in 2005, and the interior redecorated in 2013, after which the hotel joined The Luxury Collection division of Starwood Hotels.

Warsaw Uprising Youth Monument

Mały Powstaniec

| Mały Powstaniec | |

|

|

| Coordinates | 52°14′59″N 21°0′34″ECoordinates: 52°14′59″N 21°0′34″E |

|---|---|

| Location | Warsaw Old Town, Warsaw, Poland |

| Designer | Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz |

| Material | Bronze sculpture |

| Completion date | 1 October 1983 |

| Dedicated to | The child soldiers of the Warsaw Uprising |

Mały Powstaniec (the “Little Insurgent”) is a statue in commemoration of the child soldiers who fought and died during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. It is located on Podwale Street, next to the ramparts of Warsaw’s Old Town.

The statue is of a young boy wearing a helmet too large for his head and holding a submachine gun. It is reputed to be of a fighter who went by the pseudonym of “Antek”, and was killed on 8 August 1944 at the age of 13. The helmet and submachine gun are stylized after German equipment, which was captured during the uprising and used by the resistance fighters against the occupying forces.

Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz[1] created the design for the monument in 1946, which was later used to make smaller copies of its present state. The statue was unveiled on October 1, 1983 by Professor Jerzy Świderski – a cardiologist who was a courier for the resistance during the uprising (pseudonym: “Lubicz”) serving in the Gustaw regiment of the Armia Krajowa. Behind the statue is a plaque with the engraved words of “Warszawskie Dzieci” (“Warsaw Children”), a popular song from the period: “Warszawskie dzieci, pójdziemy w bój – za każdy kamień twój, stolico damy krew” (“We’re the children of Warsaw, going into battle – for every stone of yours, we will give our blood”).

More Warsaw

Warsaw at night