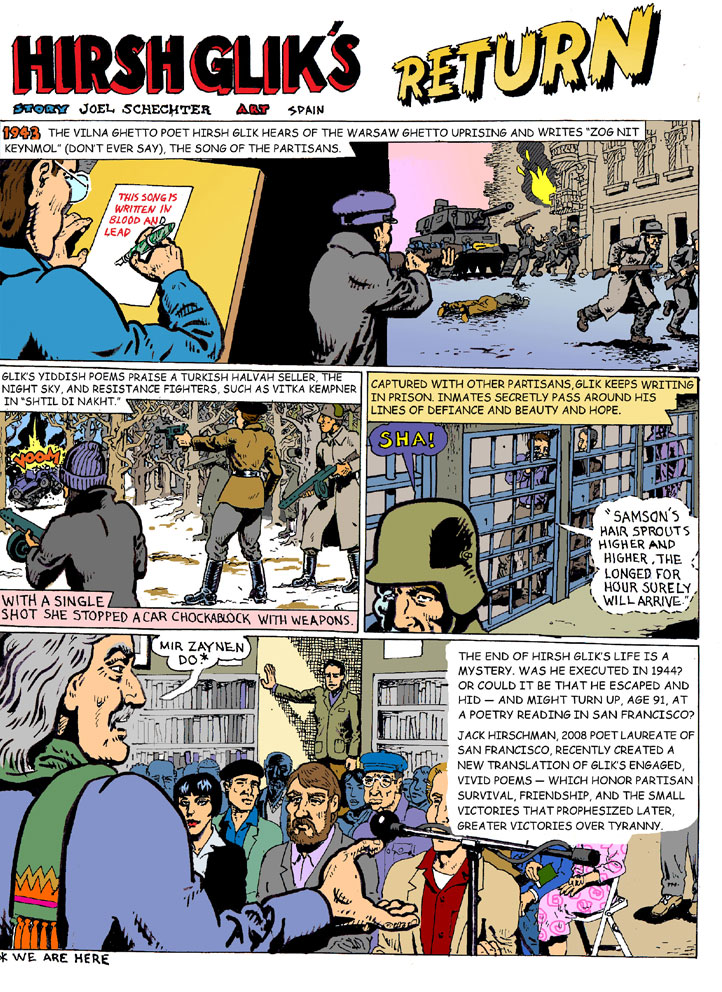

It began in the Vilna Ghetto in 1943.

As we approach the 75th anniversary of the anthem of the Survivors, we have established a program to recite the Partisan Poem, Zog Nit Kaynmol, in 23 languages around the globe.

Here is an article by Geoff Vasil which appeared overnight in the Lithuanian Jewish Community News

Don’t Give Up Hope: The Partisan Poem and Song Project

Hear it as a poem

The Poem

The Poem

The Partisan Poem It was written as a poem of hope by Hirsh Glik, aged 20, in the Vilna ghetto in 1943. In English Aaron Kremer’s English version recited by Freydl Mrocki of Shalom Aleiche…

Source: elirab.me/poem/

Read Yuri Suhl’s 1953 essay

SONG HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

By YURI SUHL 1953

Transferred by OCR from this book I sourced in the NYPL

Many songs came out of the ghettos and concentration camps of Europe during the last war. Most of these songs are of unknown authorship. They have about them the anonymity of the Pashaik-the striped prisoner’s garb-and the numbers tattooed on the victim’s arm. Singly, each depicts, both in concrete imagery and in general terms, either a particular phase of ghetto life, or the predominant mood of the ghetto dwellers at a given time. Together, they are the collective outcry of people subjected to an inhuman persecution. They form a record of martyrology and courage seldom met in human history.

These songs, though saturated with the pain and anguish that marked the life of the inhabitants of the ghetto, were nevertheless songs of hope and not of despair. The mood of resignation is absent from these songs. Their underlying theme is a deep yearning for a brighter day and an unswerving conviction that such a day will finally come and bring with it the destruction of Hitlerism and the liberation of Hitler’s victims.

With these songs on their lips the prisoners of the ghettos helped lighten the burden of their daily miseries, to face the gallows, firing squads and the torture chambers and the walk on the last path to the gas chambers. And with these songs on their lips, hushed by the rules of security, muted by the laws of secrecy, the underground met in dark bunkers to plot the strategy of the ghetto uprisings.

Some of these songs are still sung by ghetto survivors in various parts of the world; some form a part of artists’ repertories and are sung from the stage; others have become part of memories too painful to be stirred into consciousness. But one song, written in the ghetto of Vilna by a young poet named Hirsh Glik, has in the short space of a few years achieved a unique popularity. From being the official battle song of the Jewish partisans of the Vilna ghetto during the war, it has become, after the war, a hymn of Jewish people all over the world. Nachman Meisel, well-known Yiddish literary critic, writes in his booklet Hirsh Glik And His Song “Zog nisht kaynmol” [Never say]: “It is a significant and amazing phenomenon that without the sanction of any authoritative publication Zog nisht kaynmol was taken up spontaneously by all the sectors of the Jewish people as the highest and fullest expression of the sorrow and suffering, the protest and courage, that filled our hearts in the recent years of annihilation and rebirth.”

During my trip to Europe in 1948, I was able to observe at firsthand the extent of the popularity of this song and its power to move the Jews. My experience fully corroborates Mr. Meisel’s statement. I recall a spring morning in the town of Lignitz in Lower Silesia. As in every other town on my tour through Poland, several members of the local Jewish committee took me on a round of visits to Jewish institutions. We began our day with the Jewish children’s school, a large renovated building with spacious class rooms and modern facilities. The teachers had been informed beforehand of my scheduled visit. Upon my arrival, all classes were suspended and the students were assembled in a large auditorium. I greeted the several hundred pupils in behalf of the Jewish children of America and then read a story to them. In response they sang for me songs of the ghetto and of the new life in Poland. When the director announced that the visit with the American guest had come to a close, the children rose spontaneously to their feet and began to sing Zog nisht kaynmol.

I watched the expression on their faces, the look in their eyes. It was as though these young children had suddenly become mature and serious adults. They began singing slowly in a low but unfaltering tone. Gradually their voices rose, swelled to a high note and dropped again. It was not the music that controlled the volume of their voices, the even-measured cadence of their tones. It was the meaning of the words that determined their tonal emphasis. It was not just a song that they were singing. They were making a vow. They had sung this very song in the ghetto or had heard it from their fathers and mothers, who were no longer alive. Some remembered that it was with this song on their lips that partisan Jews had died fighting the nazis. For the children, the song was a firm resolve never again to be children of the ghetto. It was a song to honour the dead and to inspire courage in the living. Wherein lies the strength of this song? What single feature of its composition is the source of its popularity? Do its thoughts and sentiments express the essence of its vigour or does its form give this song its special quality? Is it the melody-strong, confident, hope giving and uplifting, yet permeated with an undertone of deep sorrow-that makes this song reach out to millions? Or do the circumstances out of which it was born endow the song with the touch of immortality?

HIRSH GLIK, RESISTANCE POET

Though each of these elements is worthy of separate treatment and serious consideration, it would be a grave error to ascribe the song’s vital message and overwhelming popularity to one single factor. Rather is it the aggregate of all these elements, combined to form one unified whole, that gives this song its quality. Any proper evaluation of it must begin with its origin and its author, Hirsh Glik.

Hirshke, as he was affectionately called, was born in Vilna in 1920. His father was a poor tradesman who eked out a precarious living. To supplement his father’s earnings, Hirshke was forced to seek a job at the age of 15. He worked as a clerk, first in a paper business and later in a hardware store. The sensitive youth was often seen going home from work late in the evening, his tired face showing the strain of long hours and hard work. The urge to write manifested itself early in Glik’s life, and his first literary products already revealed a vigour and freshness characteristic of a genuine poetic talent. He was a leading member of a young literary group of Vilna called “Yungvald,” which had published, under the editorship of the poet Leizer Wolf, several issues of a literary magazine bearing the name of the group. When the Germans occupied Vilna, and herded the Jews into a ghetto, Hirsh Glik, together with several hundred other Jews, was sent to Veisse Vake, a work camp 12 miles from Vilna. There they were set to digging peat. The working hours were long and living conditions in the camp extremely difficult. Although hard labor and inhuman treatment at the hands of the nazis robbed Glik of his physical energies, they failed to break his spirit. More than ever he was now possessed of a burning desire to record the miserable life of the work camp. Late at night, when his fellow prisoners lay exhausted on the floor of their hovels, Glik cried out both for them and himself the anguish of their souls in poetry. Many of these poems he had managed to transmit to the ghetto. He was twice awarded literary prizes for his poetry by the Jewish Writers and Artists Association of the Vilna ghetto. On several occasions he even managed to come to the ghetto himself. He would then spend most of his time in the Youth Club, reading his poetry to enthralled audiences.

In the early part of 1943, the Germans liquidated the work camp Veisse Vake and transferred all the Jews to the ghetto of Wilno. Those were not “ordinary” ghetto days. At dawn of April 5th, 4,000 Jews were put to death at Ponar. Those in the ghetto who had harboured the illusion that life in the ghetto had been “stabilised,” were suddenly shaken out of their complacency. A frantic search for weapons ensued. Then came a piece of news that electrified the ghetto. The underground radio operator picked up a brief bulletin: “The remainder of the Jews in the Warsaw ghetto have begun an armed uprising against the murderers of the Jewish people. The ghetto is in flames!”

Those flames, though geographically distant, set off sparks of revolt in other ghettos and filled the Jews with a deep sense of pride in their Warsaw brethren. They gave the call to arms. The search for weapons was more feverish than before. It was in those turbulent days under the direct impact of the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto, that Hirsh Glik wrote his immortal Zog nisht kaynmol. And when the staff of the underground met to work out strategy and assign battle stations, the song was adopted as the official battle hymn of the partisans. But the people had preceded the underground staff in this choice. Long before the staff had accorded the song this singular honour, Zog nisht kaynmol was tremendously popular in the entire ghetto.

On the first of September 1943, when the Gestapo began the liquidation of the Wilno ghetto, the partisans barricaded themselves in various parts of the ghetto to battle the Germans. Hirsh Glik and his group were surrounded by the Gestapo before they could get to their weapons. They were taken prisoner and sent to the labor camp at Goldfield, in Estonia, where conditions were even worse than in previous camps. Even the privilege of possessing pencil and paper was denied to Glik. This, however, did not prevent him from continuing his creative work. He composed and recited by heart to his fellow prisoners.

One year later, in August 1944, the rapidly advancing Red Army forced the Germans out of their positions. The nazis began to liquidate the concentration camp in an effort to erase the traces of their fiendish work. Glik realised that liquidation of the labor camp spelled death for the Jews. Together with a group of fellow prisoners he escaped to the nearby woods. There he ran into a detachment of retreating Germans and was killed in the brief encounter. He died in the true spirit of his song, fighting the enemy of his people.

Zog nisht kaynmol has attributes of a folksong-simplicity of form, an easy, natural rhyme scheme, clarity of expression and unity of mood. Not a single word or line in it is incomprehensible to the least sophisticated person. It is unaffected to the point of artlessness. Yet it has a lyrical quality, and is permeated with a richness of imagery that places it in the category of a poem of high artistic caliber. It is indeed a rare combination of simplicity and art, blending harmoniously into a unified and heightened expression. But all these elements, however fine, would not suffice to give this poem the stature it has achieved. It is the mood of the song, so clearly and forcefully expressed, which is the core of this poem’s strength, vigour and durability. In this Zog nisht kaynmol Hirsh Glik has succeeded in articulating the prevailing mood and feelings of the Jews of the ghetto of Wilno and of resistance in all other ghettos and concentration camps. He had forged a fighting weapon.

The poet had adapted his words to an appropriate melody. The music was originally a Cossack Cavalry song composed by the Pokrass brothers, two Jewish Soviet composers, for a poem written by the Soviet poet A. Surkov.

Although words of the Cossack song are not related to the content of Glik’s poem, the music seems to blend harmoniously with the words of Zog nisht kaynmol. Without straining for symbolism, one cannot help but reflect on this association-a Soviet, Cavalry song wedded musically to a Jewish partisans’ battle poem. It is known that in areas liberated by the Red Army other Jewish partisans changed the fourth line of Glik’s song from “Svet a poyk tun undser trot; Mir zenen doh!” (Our marching steps will thunder: we are here) to: “Die Stalinshe chavayrim zenen doh!” (The comrades of Stalin are here).

Zog nisht kaynmol has been translated into many languages. We know about versions in Rumanian, Dutch, Polish (three versions), Spanish, Hebrew and English (five versions). Of the five English versions, that of the young Jewish American poet Aaron Kramer seems to me the most successful. “Niederland Film,” a Dutch film company, produced a documentary based on Glik’s song in 1947. And the famous Soviet Jewish poet, Peretz Markish, created an heroic character based on his conception of Hirsh Glik in his monumental Yiddish poetic work, War.

Thus a Yiddish song, inspired by the heroic uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto, written by a young Jewish partisan in the Wilno ghetto and adopted by the partisans of this ghetto as their offal battle hymn, has reached out to the far corners of the globe to become a battle song for peace for millions of people. For the message of this song, the warning it sounds, is as timely and vital for us today, when nazism is being restored in Western Germany became a battle song for peace for millions of people, as it was to the embattled Jews of the ghettos and the fighting Jews in the woods. In these days, when the architects of war pacts and the cold war use every device to sow gloom and despair in the hearts of the people, every expression of strength, courage and reaffirmation of faith in democracy is a rallying force. Hirsh Glik’s Zog nisht kaynmol is, in this sense, a weapon in the arsenal of democracy.

Please contact me for further details:

eli@elirab.com

Thanks

Eli

Like this:

Like Loading...