Novogrudok School #4

14 May 2018

The IAJGS International Jewish Cemetery Project mission is to catalogue every Jewish burial site throughout the world. Every Jewish cemetery or burial site we know of is listed here by town or city, country, and geographic region is based on current locality designation.

Source: www.iajgsjewishcemeteryproject.org/belarus/navahrudak.html

Source: kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/navahrudak/Home.html

First Site

Second site

Third site

WWII

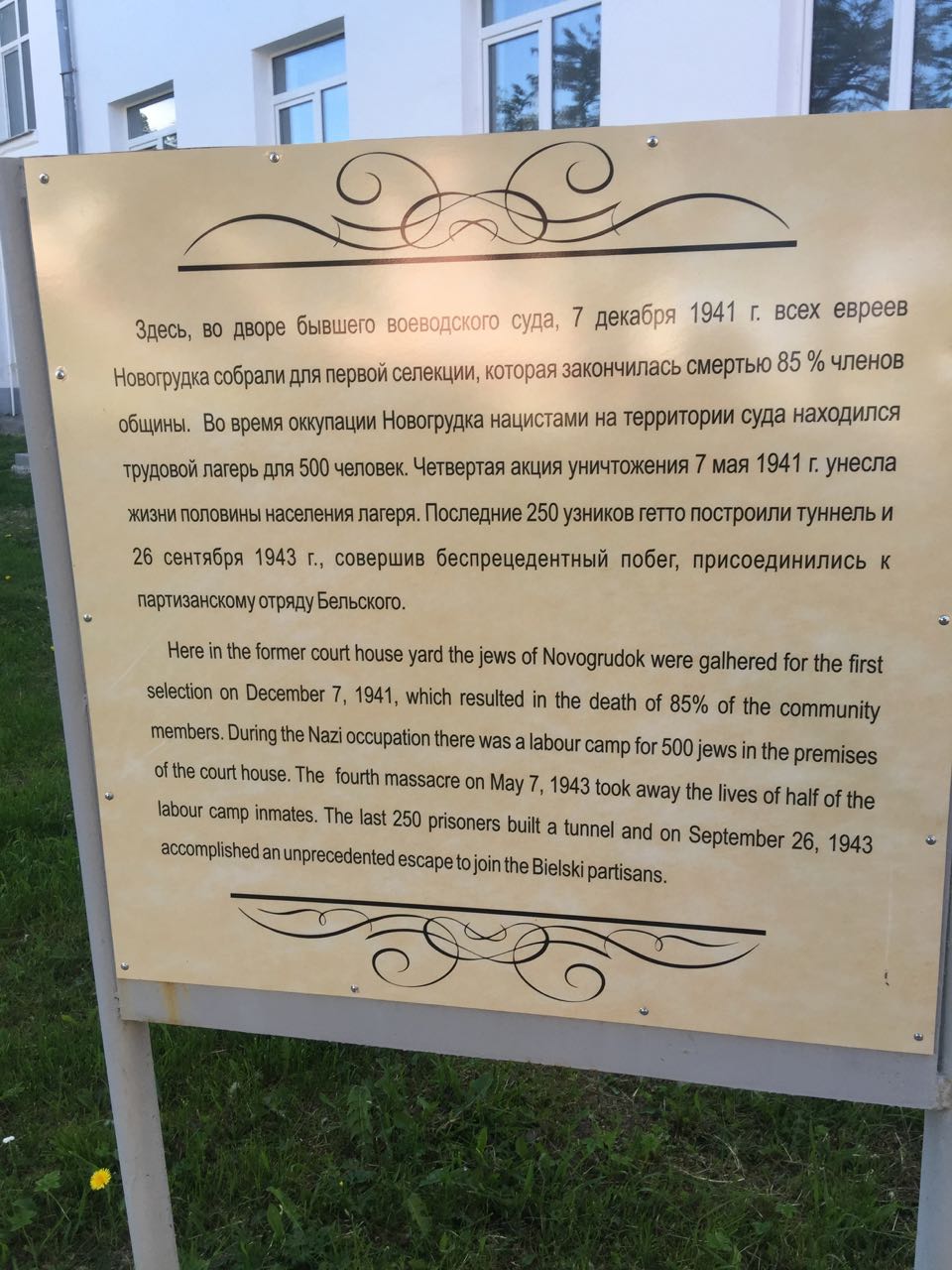

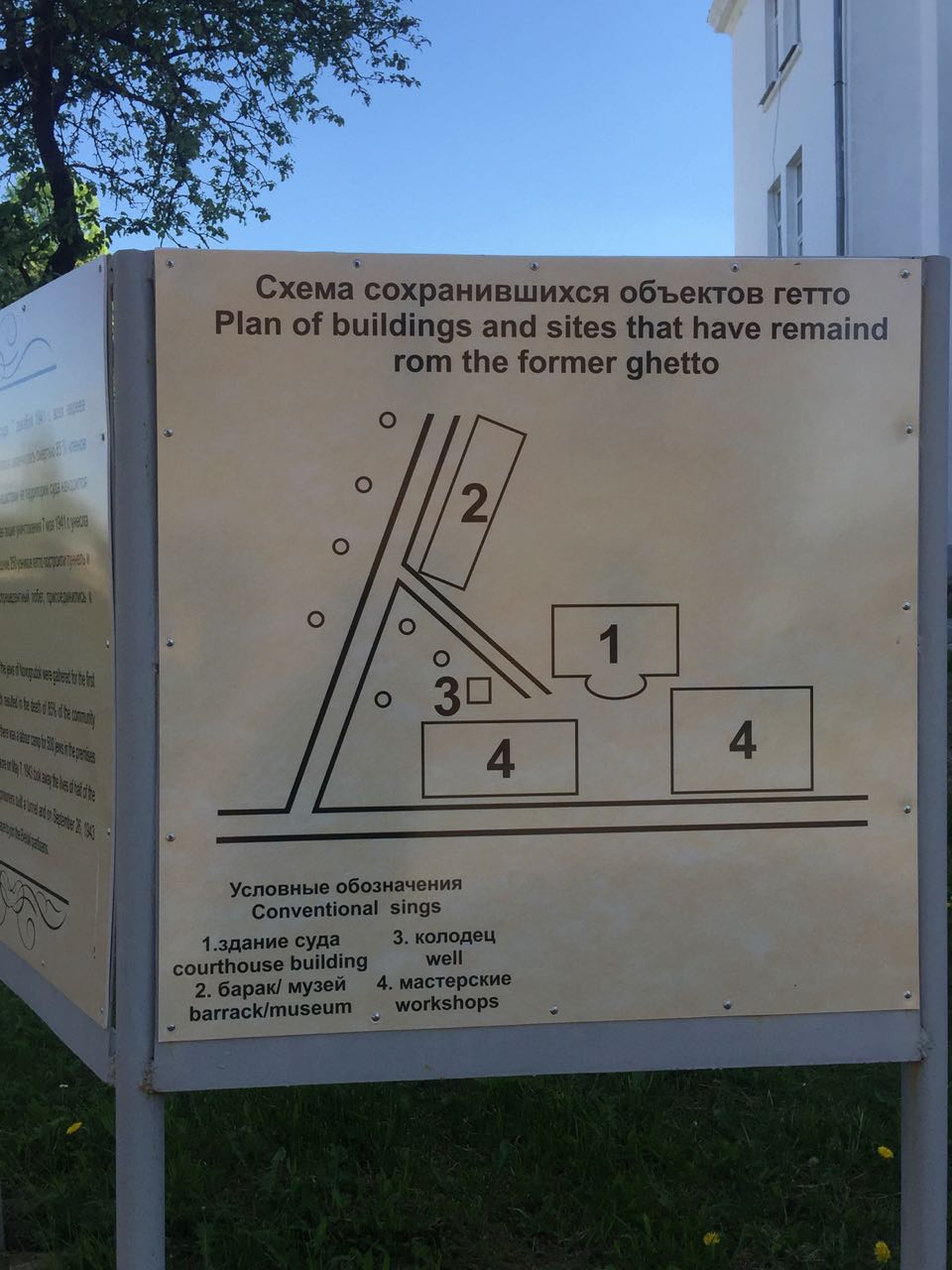

Soviet troops entered the city in 18 September 1939 and it was annexed into the Soviet Union via the Byelorussian SSR. The Polish inhabitants were exiled, mostly to Siberia and the Soviet Union, as prisoners. In the administrative division of the new territories, the city was briefly (from 2 November to 4 December) the centre of the Navahrudak Voblast. Afterwards the administrative centre moved to Baranavichy and name of voblast was renamed as Baranavichy Voblast, the city became the centre of the Navahrudak Raion (15 January 1940). On 22 June 1941 Nazi Germany invaded the USSR and Navahrudak was occupied on 4 July, following one of the more tragic events when the Red Army was surrounded in what’s known as the Novogrudok Cauldron. See Operation Barbarossa: Phase 1.

During the German occupation it became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland territory. Partisan resistance immediately began. The Bielski partisans made of Jewish volunteers operated in the region. On 1 August 1943, Nazi troops shot down eleven nuns, the Martyrs of Nowogródek. The Red Army reoccupied the city almost exactly three years after its German occupation on 8 July 1944. During the war more than 45,000 people were killed in the city and in the surrounding area, and over 60% of housing was destroyed.

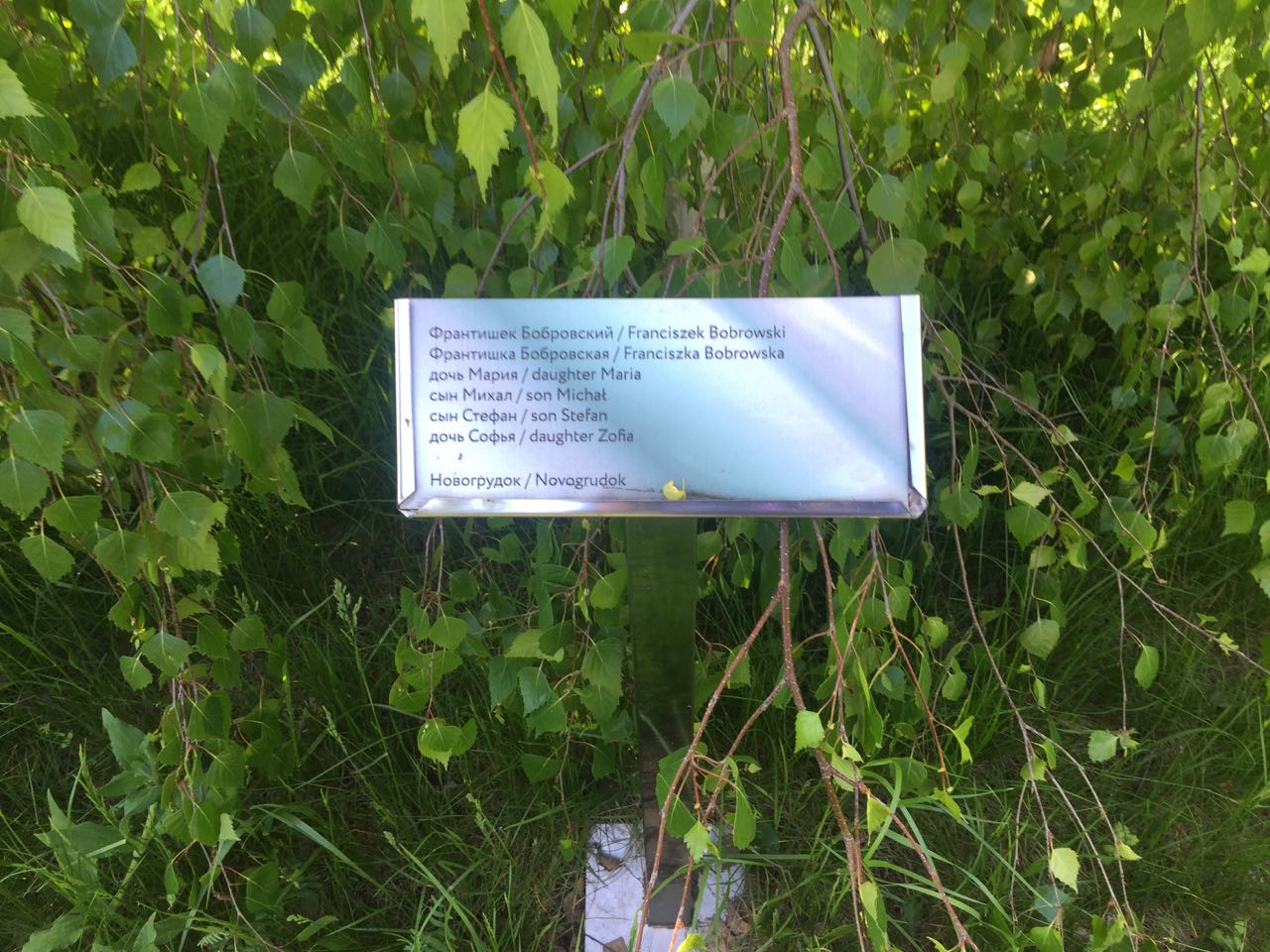

Navahrudak was an important Jewish center and shtetl. It was home to the Novardok yeshiva, led by Rabbi Yosef Yozel Horwitz, as well as the hometown of Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein and of the Harkavy Jewish family, including Yiddish lexicograph Alexander Harkavy. Before the war, the population was 20,000, of which about half were Jewish; Meyer Meyerovitz and Meyer Abovitz were the Rabbis there at that time. During a series of “actions” in 1941, the Germans killed all but 550 of the approximately 10,000 Jews. (The first mass murder of Navahrudak’s Jews occurred in December 1941.) Those not killed were sent into slave labor.[3]

Video

Tamara Vershitskaya 14 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/iB1okmue4fg

Video

Novogrudak School #4

Source: youtu.be/PDIGVhRKH3E

Source: kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/navahrudak/Museum_of_History.html

Lenin

Official press releases, Belarus

Video

Beis Aharon School Pinsk Belarus 13 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/vi86WhEv3tA

Video

Beis Aharon Bielski School

Source: youtu.be/yN3QGZkmGjY

Video

Beis Aharon Bielski School Pinsk 13 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/qawR9BEqqjM

The Yad Yisroel is non for profit 501(C)(3) organization which was started by the Stoliner Rebbe in 1990. Yad Yisroel is an organisation with a goal to bring Russian Jews closer to their heritage.

Video

sung by Cantor Harry Rabinowitz 1959 Beis Aharon School Pinsk 13 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/XQDfkp1s1ys

Oyfn Pripetshik (Yiddish: אויפן פריפעטשיק, also spelled Oyfn Pripetchik, Oyfn Pripetchek, etc.;[1] English: “On the Hearth”)[2] is a Yiddish song by M.M. Warshawsky (1848–1907). The song is about a rabbi teaching his young students the aleph-bet. By the end of the 19th century it was one of the most popular songs of the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, and as such it is a major musical memory of pre-Holocaust Europe.[3] The song is still sung in Jewish kindergartens.

Video

Great (great) grandson of Chaim Soloveitchik Halevy Beis Aharon Bielski School Pinsk 13 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/y-D_ssh8S4A

Video

Great (great) grandson of Chaim Soloveitchik Halevy who taught my Zaida Nachum Mendel Rabinowitz in the Brisk Yeshiva c1905 Beis Aharon Bielski School Pinsk …

Source: youtu.be/IOA1FS6dkrE

Video

Source: youtu.be/I_ik3K4I1zw

Video

Source: youtu.be/roYeLnUqVXo

Video

Source: youtu.be/Q4TQ0gIeSWk

The Pinsk massacre was the mass execution of thirty-five Jewish residents of Pinsk on April 5, 1919 by the Polish Army. The Polish commander “sought to terrorize the Jewish population” after being warned by two Jewish soldiers about a possible bolshevik uprising.[1]. The event occurred during the opening stages of the Polish-Soviet War, after the Polish Army had captured Pinsk.[2] The Jews who were executed had been arrested were meeting in a Zionist center to discuss the distribution of American relief aid in what was termed by the Poles as an “illegal gathering”. The Polish officer-in-charge ordered the summary execution of the meeting participants without trial in fear of a trap, and based on the information about the gathering’s purpose that was founded on hearsay. The officer’s decision was defended by high-ranking Polish military officers, but was widely criticized by international public opinion.

Pinsk is a town, a district center in Brest region. It is situated on the bank of Pina River (the left tributary of Pripyat) 186 km to the east from Brest, 304 km to south-west from Minsk. It has a railway station on the line Brest-Homel.

Source: shtetlroutes.eu/en/pinsk-cultural-heritage-card/

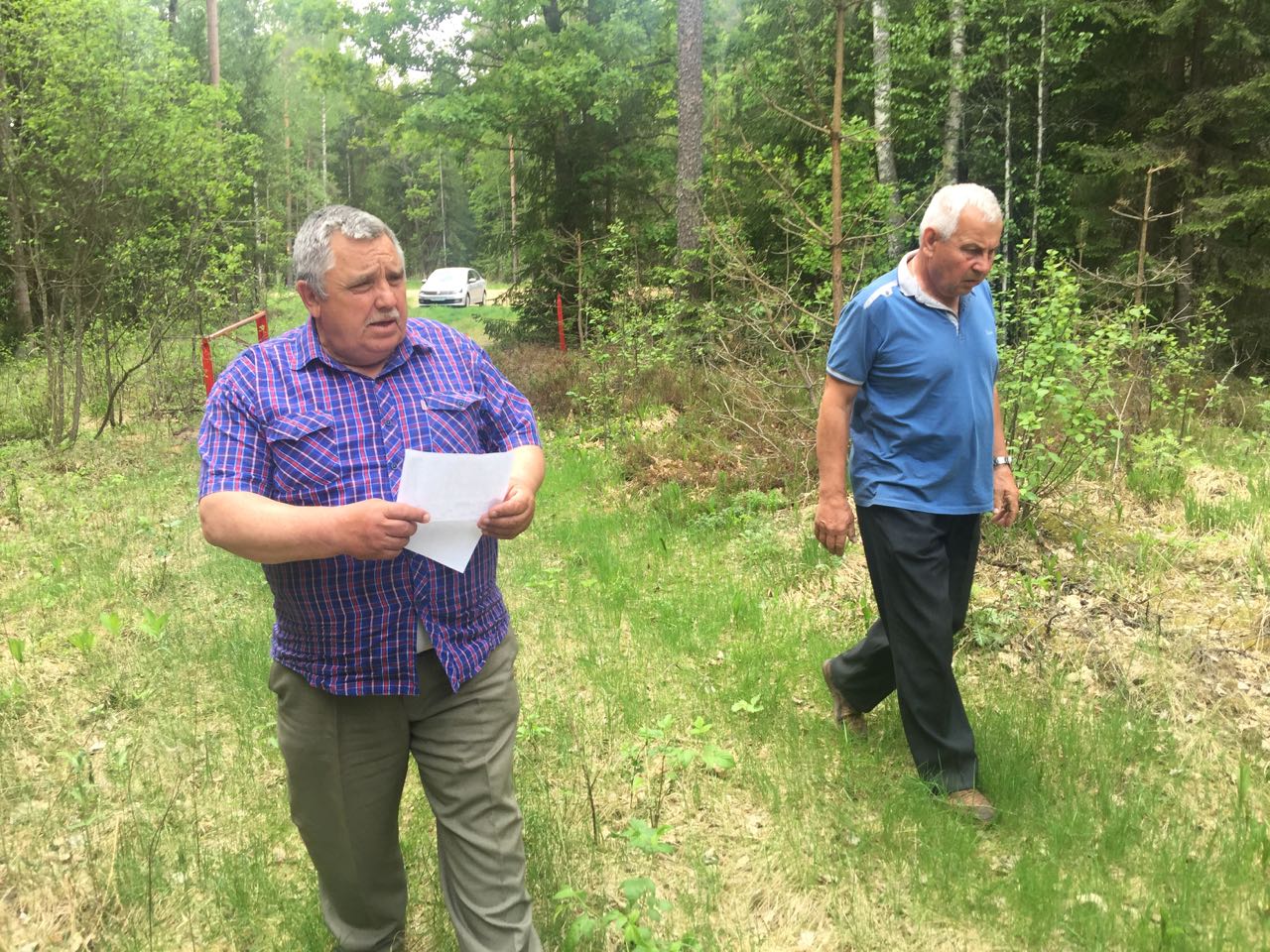

My visit to the Naliboki Forest in Belarus on 16 May 2018, with Tamara, Alexander and Ivan.

This is where the Bielskis and many other partisans had their camps in the latter part of WWII. Aptly named Forest Jerusalem.

Please watch the nine videos of Tamara telling us more.

The road into the forest.

Naliboki Forest (Belarusian: Налібоцкая пушча, Nalibotskaya Pushcha (pushcha: wild forest, primeval forest)) is a large forest complex in the northwestern Belarus, on the right bank of the Neman River, on the Belarusian Ridge.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naliboki_forest

Alexander and Ivan walking towards the partisan camp.

Tamara Vershitskaya in the Naliboki Forest

Source: youtu.be/oaL75ktaeVs

Tamara Vershitskaya

Source: youtu.be/wt1odw9pU9c

A metal bucket

Tamara Vershitskaya

Source: youtu.be/HQ8HCRYDVJM

Tamara Vershitskaya talks about the Naliboki Forest and the Bielskis

Source: youtu.be/q6u8qcKO7Cg

Tamara Vershitskaya

Source: youtu.be/5C_M-kNrJiA

Tamara Vershitskaya

Source: youtu.be/OKc_wMsKxwE

Tamara Vershitskaya

Source: youtu.be/bOKtffhGIkk

Tamara Vershitskaya talks about Naliboki Forest and Bielskis with Alexander Pilinkievich

Source: youtu.be/Uc6O0YJUyfc

Ivan preparing our picnic lunch near the fire ranger

A VERY treif lunch – I had the herring!

Beekeepers

Trees for sale

www.arielluckey.com www.comuntierra.org In May 2013, the Luckey Brothers journeyed to their great-great-grandfather’s childhood village Lubca in rural Belaru…

Source: youtu.be/XPCGtmxd2Hk

Source: elirab.me/zog-nit-keynmol/

The Bielski partisans were an organization of Jewish partisans who rescued Jews from extermination and fought against the Nazi German occupiers and their collaborators in the vicinity of Nowogródek (Navahrudak) and Lida in German-occupied Poland (now western Belarus). They are named after the Bielskis, a family of Polish Jews who led the organization.

Nalibaki (Belarusian: Налібакі, Russian: Налибоки, Polish: Naliboki) is an agrotown in Minsk Region, in western Belarus.

Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalibaki

Tamara Vershitskaya 16 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/TU2ZVBzldtE

Tamara Vershitskaya, Alexander Pilinkievich, chairman of the local village council, and Ivan – builder 16 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/Nf3QBLP-YYA

Tamara Vershitskaya and Ivan 16 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/aFb4YnB9j4Q

Tamara Vershitskaya talks about the mikvah in Naliboki Belarus 16 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/lndsEPiKshM

The Naliboki massacre (Polish: Zbrodnia w Nalibokach) was the mass killing of 129 Poles,[2] including women and children, by Soviet partisans[3] on 8 May 1943 in the small town of Naliboki[4] in German-occupied Poland (the town is now in Belarus).[5] Before the 1939 German-Soviet invasion of Poland, Naliboki was part of Stołpce County, Nowogródek Voivodeship, in eastern Poland.[1]

The Lost Shtetl Museum of Seduva Jewish History Ground Breaking Seduva, Lithuania Friday 4 May 2018

Source: youtu.be/-jE7oEIjg_c

Here is the transcript of my speech:

My name is Eli Rabinowitz.

I live in Perth Australia and I am a Litvak!

I was born in Cape Town South Africa, and my heritage is firmly rooted in this region.

I have visited Lithuania each year since 2011, this being my 8th visit.

In 1811 my 3rd great grandfather, Zalman Tzoref Salomon, was one of the first to leave Lithuania for Jerusalem where he successfully established the Litvak community in the Old City.

Litvaks were resilient and achieved significant successes, and, members of my Salomon family founded the town of Petach Tikva, the first Hebrew newspaper, the Hurva Synagogue, and Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Many Litvaks later migrated to South Africa, aptly named, the “goldene medina”.

Jewish life in the small South African country towns often mirrored the Litvak shtetl. Many of these migrants and their families were happy, successful and safe in their new surroundings.

We often heard stories from “der heim”, describing the rich Jewish cultural life throughout Lithuania, which had existed over many centuries.

Those Litvaks who left Lithuania before the Holocaust were indeed lucky! More than 95% of the Lithuanian Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, a greater percentage than any other country!

So why do I return from the Litvak diaspora to reconnect to my roots?

It is my journey of discovery, to understand my family in the context of Jewish cultural history and history of the region. By being here, I am able to experience the traces of memory first hand, to find some remnants, clues as to how Litvak life was.

I share these on my blog and on the 35 Lithuanian shtetl websites that I write and manage.

I also work with high schools in Kedainiai, Kalvarija and Vilnius to teach students about Jewish cultural history and the Holocaust from the Jewish perspective, and then I lead collaboration classes for these schools and students around the globe. I am expanding this to more schools in Lithuania.

A growing number of articles and books are being written about family stories and Jewish life in the shtetl. This is to keep alive stories that would otherwise be forgotten. I participate in this activity as well as lecture at international conferences.

All these elements will come together when this wonderful museum opens.

It is located right in the heartland of the Litvak world, of the Litvaks I have just described as well as their descendants.

In the future, when we visit this museum, we will be able to access the past with a better understanding of history. We will view the collection of objects and artifacts, giving us an insight into how our ancestors lived their cultural, religious, work and home lives.

We will learn about their values from their daily lives and from the items they kept and used.

The museum will showcase the richness and the importance of Litvak shtetl life of years gone by. It will also reflect on the Jewish world that was destroyed by the Holocaust. The museum will educate Lithuanians and visitors to Lithuania and so provide an opportunity to learn from our history and strive for a better world.

This museum will be a beacon of preservation and attract many in the Litvak diaspora to come and visit Lithuania and their shtetls, and like me, to reconnect with their heritage.

This museum is a most appropriate way to honour the memory of the members of our families who were born, lived and died here!

Finally, the words written by Hirsh Glik in the Vilna ghetto in 1943:

“This says that although it looks like the last moments of the life of the Jewish people, it is not, and where the blood was shed, will begin a new, a heroic and a wonderful Jewish life!”

(Quote: Cantor H Fox)

Your Excellences, Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Guests:

As the project manager, I thank all of you who have gathered here. I am also endlessly grateful to the people of Šeduva for their help and goodwill, the Šeduva eldership and mayor of Radviliškis Antanas Čepononis and the municipality for close cooperation. I sincerely thank all the international team that is working on the creation of the museum – the architect from Finland, Rainer Mahlamaki; Augustas Audėjaitis and his colleagues; the design company, Ralph Appelbaum Associates, from the United States; the Swiss company ECAS and David Duffy; Jonas Dovydaitis, the director of the Šeduva Jewish Memorial Fund; the large team of international consultants; Milda Jakulyte, the Curator of the Museum as well as her colleagues; the construction supervision company Ekspertikaand Kastytis Skiečius; as well as the construction company Agentus. A huge thank you goes out to the patrons, without whose hard work and financial support this project would be impossible.

When we talk about the past of Lithuanian Jewry, we often say that “time was merciless”. Merciless to human beings, merciless to things they had created, merciless to heritage and memory. But time is not anonymous. We cannot put all the blame and guilt on it. We create time. It depends on us what time will be like. It depends on the here and now. Memory is the responsibility of all of us.

There is no museum yet. We are only about to start building it. We do this in order to create a “time” the next generations could not call merciless.

Now we are near the restored Jewish cemetery, and beneath its every stone there rests the remains of a person. A person who lived and worked, loved and prayed, sewed and cured. Not far from here, there is a place of eternal rest of those who were brutally murdered, for whom some of their former neighbors showed no mercy.

That is why we are about to build another monument – the Lost Shtetl Museum. To remember all of them. You can abandon a cemetery and steal the remaining gravestones from it. You can kill a person, loot their home, steal their belongings, burn their temple, but it is impossible to kill their memory. Lithuanian Jews and their legacy cannot live only in commemorations and solemn speeches. No matter how beautiful they are. We have left traces under the Lithuanian sky. And this museum will commemorate them.

We have decided to put the following words from the novelShtetl Love Song by Grigory Kanovich into the symbolic time capsule marking the beginning of the construction:

„It was bitter to realize the truth that from now on it was the fate of that dead tribe to be born and live only in the true and painful words of impartial memory in which it was imposible to drown the echoes of love and gratitude towards our forebears. Whoever allows the dead to fall into oblivion will himself be justly consigned to oblivion by future generations .“

Now I would like to invite Giedrius Puidokas, an 11thgrade student of the Šeduva Gymnasium and Gabriela Jeliasevič and Gabika Kondratavičiūtė, 11thgrade students of Vilnius Sholom Aleichem Gymnasium, to place a symbolic time capsule marking the beginning of the construction of the Lost Shtetl Museum.

The Maccabean Newspaper – 20 April 2018

Photos by Sas Saddick

See some videos of the commemoration here:

Yom Hashoah Perth Commemoration Sara Kogan-Lazarus sings Tsi Darf Es Azoy Zayn Sara Kogan-Lazarus sings Tsi Darf Es Azoy Zayn Yom Hashoah Commemoration Perth, Australia 15 April 2018 Yiddish Sour…

Source: elirab.me/yh18/

A punk version of Zog Nit Keynmol by Yidcore

Yom Hashoah Commemoration Perth, Australia 15 April 2018 Yiddish

Source: youtu.be/iOZqDWK0AkE

The Partisans’ Song, Zog Nit Keynmol, written by Hirsh Glik, age 22, in the Vilna Ghetto in 1943, is one of the most powerful songs of resistance and defiance ever written.

After music was added, it became the hymn of the Jewish Partisans, the rallying cry to never give up hope and to continue fighting the Nazis.

It was the anthem of those incarcerated in the ghettos and in the camps, and since the end of the Shoah, it has been sung around the world as the Holocaust Survivors’ anthem.

In 1972 Leizar Ran wrote:

“Glik wrote a poem dedicated to the Jewish catastrophe, resistance and perseverance.

Now the poem belongs to the young post-war generations of proud Jews who accept the torch of Jewish continuity and survival into their hands.”

So what happens now as our survivors depart the centre stage? The next generations will need to embrace Hirsh Glik’s legacy!

In January 2017 I was invited by King David Schools in Johannesburg to address their 1000 high school students to explain the meaning and significance of the Partisans’ Song, which is recited in Yiddish at their Holocaust commemorations.

I achieved this by using short video clips and other social media to bring it to life.

The Partisans’ Song Project was born.

Through the support of World ORT, schools in the Former Soviet Union added their own videos to the project and participated in online collaborations hosted by Herzlia School in Cape Town.

The project continues to grow through the activities of these schools and the availability of the resources on my website.

The Partisans’ Song resonates with the broader community as well. Paul Robeson sang it in Yiddish as a protest song at his concert in Moscow in 1949. Others have also adopted the song.

Presentations to black school students in South Africa, and to student teachers at Edith Cowan University, are important recent additions to the project.

Now please turn your attention to the short video created specially for tonight’s commemoration.

Please give meaning to the significance and context to the Partisans’ Song, written by Hirsh Glik 75 years ago. Please ensure that your children and grandchi…

Source: youtu.be/Yq7SrTNZPaI

As we sing Zog Nit Keynmol, now with a better understanding, let us all actively ensure that our children and grandchildren embrace this legacy of hope for peace, and for a better world for all!

Zog nit keyn mol, az du geyst dem letstn veg,

Khotsh himlen blayene farshteln bloye teg.

Kumen vet nokh undzer oysgebenkte sho,

S’vet a poyk ton undzer trot: mir zaynen do!

Fun grinem palmenland biz vaysn land fun shney,

Mir kumen on mit undzer payn, mit undzer vey,

Un vu gefaln iz a shprits fun undzer blut,

Shprotsn vet dort undzer gvure, undzer mut!

S’vet di morgnzun bagildn undz dem haynt,

Un der nekhtn vet farshvindn mit dem faynt,

Nor oyb farzamen vet di zun in der kayor –

Vi a parol zol geyn dos lid fun dor tsu dor.

Dos lid geshribn iz mit blut, un nit mit blay,

S’iz nit keyn lidl fun a foygl oyf der fray,

Dos hot a folk tsvishn falndike vent

Dos lid gezungen mit naganes in di hent.

To zog nit keyn mol, az du geyst dem letstn veg,

Khotsh himlen blayene farshteln bloye teg.

Kumen vet nokh undzer oysgebenkte sho –

S’vet a poyk ton undzer trot: mir zaynen do!

The Partisans’ Song Yom Hashoah Perth Jewish Community 15 April 2018

Source: youtu.be/JEUBJyIX4Cg

The intro by Simon Bloom

Intro by Eli

Zog Nit Keynmol by Sara Kogan-Lazarus

Zog Nit Keynmol – The Partisans Song Simone Bloom Eli Rabinowitz Sara Kogan-Lazarus 15 April 2018

Source: youtu.be/HMLrvjyhAy0

Yom Hashoah 15 April 2018 Perth Australia

Sorry for the camera focus issues in the middle of this video!

Source: youtu.be/i5zt7lArLq8

Yom Hashoah Commemoration Perth, Australia 15 April 2018 Yiddish

Source: youtu.be/hGTcZVdYp_w

Thanks to Sas Saddick for the photos and helping with the video

Thanks to Sas Saddick for the photos and helping with the video

Every year on Yom Hashoah – the Day of Remembrance of the Holocaust and Heroism, Holocaust survivors and Jewish communities sing the song Zog Nit Keynmol (‘We are Still Here’), which is also known as the Partisan Song. Now, a new initiative by Cape Town born Eli Rabinowitz seeks to teach the song to schoolchildren across the globe, allowing them to connect with each other and their history.

Source: youtu.be/tnaCtuqVBgg

This video also appears on:

April 16, 2018

The Partisans’ Song Project, in which the Herzlia Vocal Ensemble participated, is featured in Simcha – A Celebration of Life… on SABC TV2 .