We are very pleased to inform you that the following proposal has been accepted for presentation at the 38th IAJGS International Conference on Jewish Genealogy in Warsaw, Poland from August 5 -10, 2018.

Schedule

2018 Conference ScheduleAbtract #1

The Partisan Song Project and Genealogy – Inspiring and Connecting a New Generation

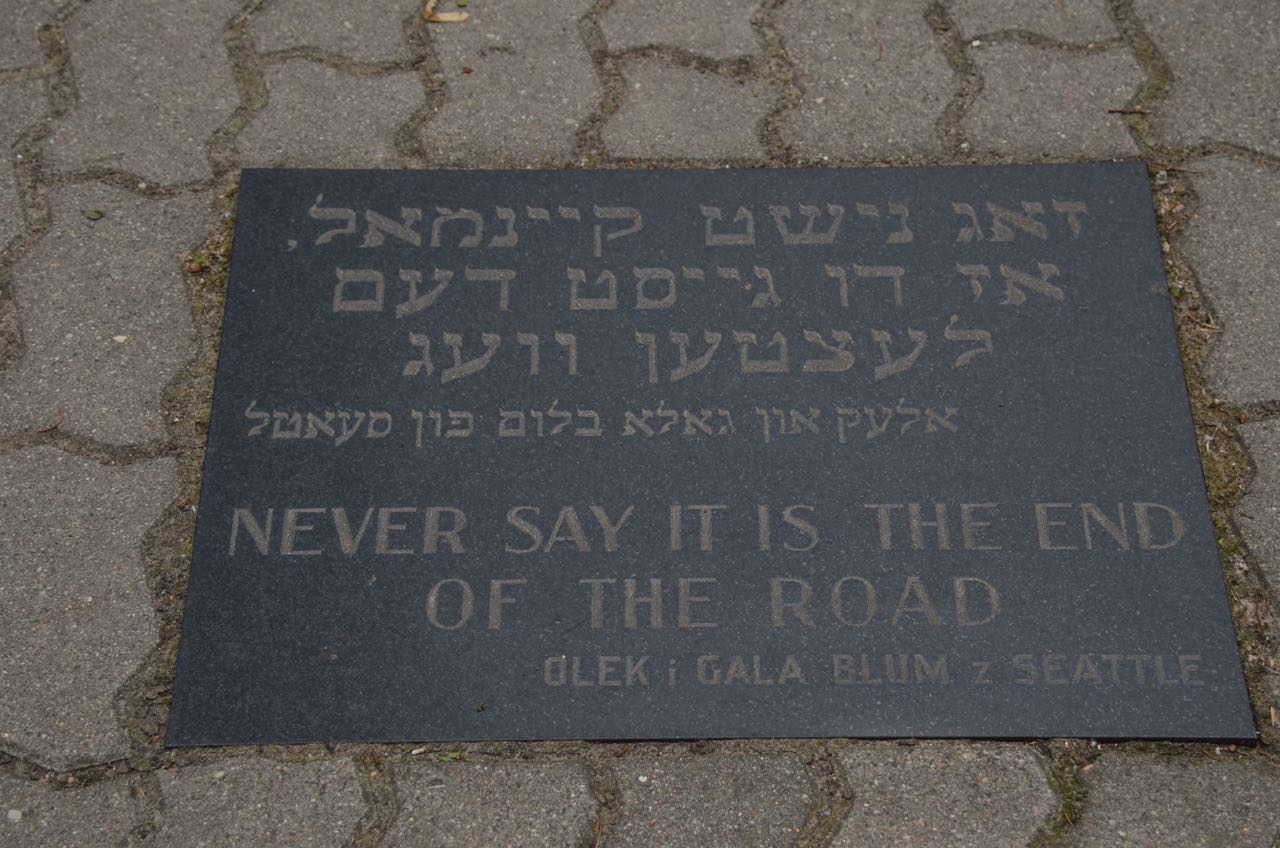

“Zog Nit Keynmol” is the anthem of Holocaust survivors. It is a legacy that is in danger of soon dying out. The Partisan Song Project is an initiative to connect it to the next generation through meaning, context, and family histories.

This multi-media presentation follows the path of the project from its genesis in January 2017:

the initial request from a school for information;

my research methodology and content;

my “out of the box” teaching style to 1000 students;

planning and running a separate online class with five schools in the FSU and hosted by a sixth;

introducing family history to the program;

working with more schools;

spreading the message via social media, Holocaust centres and survivors;

going global with the support of World ORT; HET UK, TEC Lithuania, Yad Vashem; and

the case study of Oscar Borecki, a Bielski Partisan from Novogrudok and commemorating his legacy in Australia.

Handout

Warsaw Handout 1Abstract #2

Back From the Polish and Litvak Diaspora: Virtual Journeys That Connect Us To Our Roots.

Back From the Polish and Litvak Diaspora: Virtual Journeys That Connect Us To Our Roots.

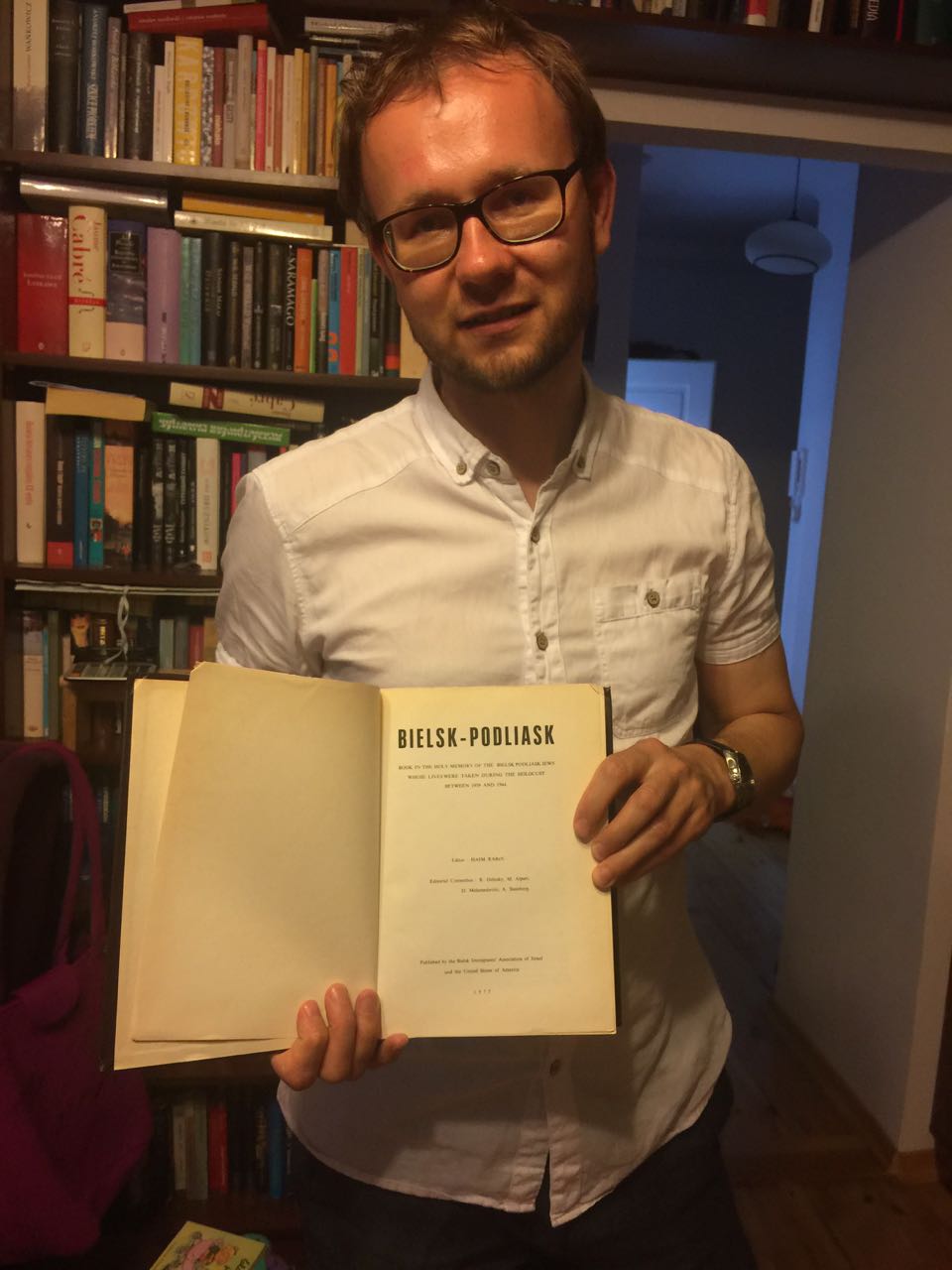

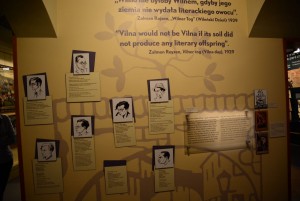

My first heritage visit to Poland and the Baltics was in 2011. I have returned six times since, accumulating a wealth of information, photos, stories and contacts.

In this multimedia presentation find out why and how we gather and share this data with others in mind; and why we include both past and contemporary Jewish Life.

I will help you grasp the importance of the web using the following tools, drawing on some examples:

JewishGen KehilaLinks – my 80 KehilaLinks (35 Lithuania, 7 Poland, 6 Belarus, others in Latvia, Germany, Russia, Estonia, China, Africa and Australia);

WordPress – 600 posts and pages that make up my tangential travel and Jewish Life website http://elirab.me;

online classrooms which can simultaneously connect nine schools at once;

Google, including Google Search, YouTube, Translate, Maps, Earth, Hangouts, Chrome and Drive;

social media networks such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn; and

additional resources such as Wikipedia

Handout

Warsaw Handout 2

Warsaw KehilaLink

I am pleased to advise I have taken on the important project of creating

and running the Warsaw KehilaLink.

It is quite surprising that there has been no KehilaLink for Warsaw,

once the largest Jewish city in Europe and the second largest in the

world after New York.

JewishGen KehilaLinks (formerly “ShtetLinks”) is a project

facilitating web pages commemorating the places where Jews have lived.

Kehila [Hebrew] n. (pl. kehilot): is used to refer to a Jewish

community, anywhere in the world.

KehilaLinks are hosted by JewishGen, the world’s largest Jewish

genealogical organisation. It has a user base of over 500,000 registered

users worldwide.

I invite you to send in your stories, memories, photos and family

biographies.

The link to the site under construction:

Warsaw

IAJGS Orlando 2017

IAJGS Orlando

Orlando Jewish Info – Your Jewish Guide to Orlando Orlando Jewish Info – Your Jewish Guide to Orlando Orlando Jewish Info Guide Source: www.orlandojewishinfo.com Getting there The Swan …

Source: elirab.me/iajgs-orlando/