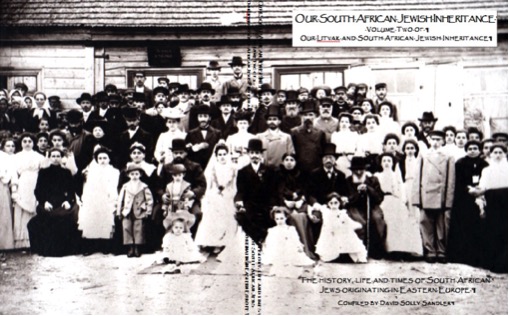

David Sandler has just launched his latest book.

Selfie of David Sandler and me at my home in Perth

Just in from David:

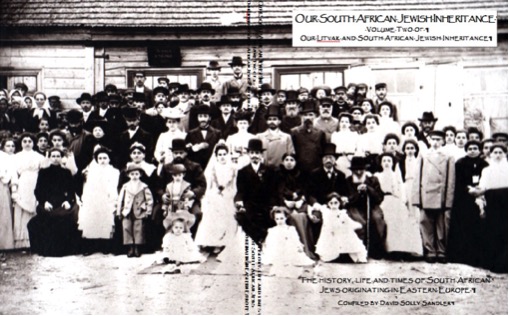

OUR SOUTH AFRICAN JEWISH INHERITANCE compiled by David Solly Sandler published August 2016

The matching volume to OUR LITVAK INHERITANCE published in March 2016

These two volumes tell of the history, life and times of South African Jews originating in Eastern Europe

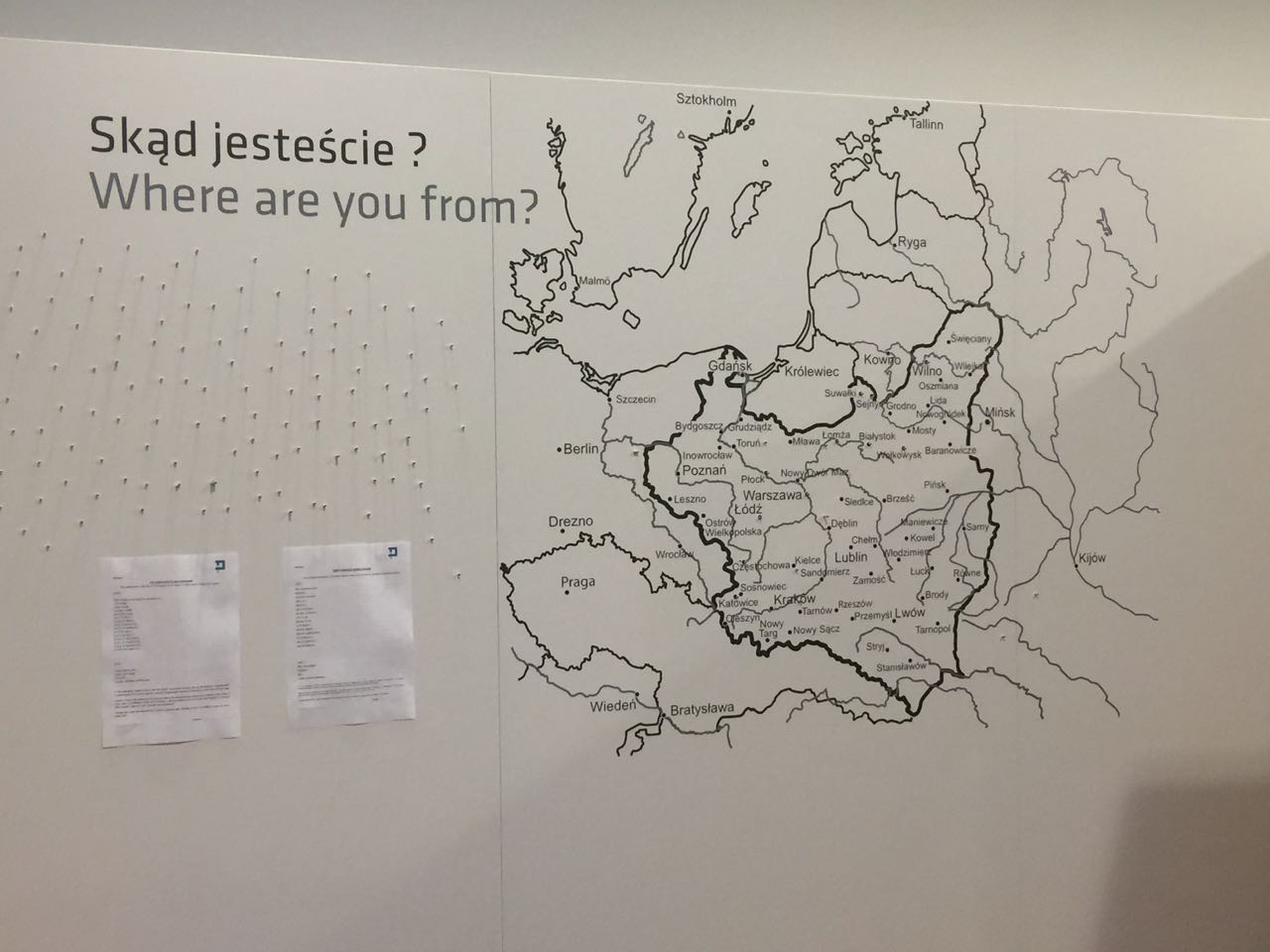

Like most South African Jews, my ancestors emigrated from Lithuania to South Africa between 1880 and 1920. We were the lucky ones escaping the horrors of the Holocaust and most of us have relatives left behind in Lithuania who perished in the Holocaust.

For about 100 years we generally prospered and multiplied in South Africa and then in the early 1970s, seeking more secure futures for our families, we commenced immigrating to Israel, the UK, the USA, Canada and Australia and by the year 2000 about 50,000 of the 120,000 South African Jews had emigrated.

Like my other books this is a compilation and not a single narrative. It is a gathering of articles, stories and histories that tell us of life and history and Jewish life and history in South Africa from 1880 to 1990. As it is a gathering of articles, stories and histories in some cases we will have two or more different views of the same event.

The purpose of this book is to tell the history of South Africa and our Jewish contribution, with its rich Litvak culture, and to share it with our children and grandchildren. Another purpose of the book is to raise funds for Arcadia and Oranjia, formerly the two Jewish Orphanages in South Africa.

This 511 paged softcovered book has the following sections

1 The early history of South Africa in the Western and Eastern Cape Province.

2 Kimberley and the discovery of Diamonds (Northern Cape)

3 The Establishment of Natal, The OrangeFree State and The Transvaal Boer Republics

4 The discovery of Gold in the Witwatersrand and the founding of Johannesburg

5 The Anglo Boer War 1899-1902

6 Immigration, Yiddish, Zionism and Jewish Culture

7 World War One

8 The Generosity of the S A Jewish Community

9 Landsmanschaften Mutual Aid Societies

10 World War Two

11 Jewish Life in Country Communities (1947 & 1948)

12 Jewish Communities and Personalities

13 Support for Israel during the Israeli War of Independence (1948 & 1949)

14 The Struggle from Apartheid to Multi-racial elections

Between 1981 to 2005 some 40% of Jews, about 47,000 left South Africa. About 13,000 went to Israel, 12,000 to the US, 11,000 to Australia and New Zealand, 6,000 to the UK and 5,000 to Canada.

Most South African Jews today live in Johannesburg (50,000) and Cape Town (16,000), while the other main centres are Durban (2,700) and Pretoria (1,500). Originally, the community was evenly spread throughout the country, but the rural communities began declining shortly after World War II and are today largely defunct.

PG compilation still to come:

I invite all South Africans to share their family histories and photos for the following two books.

– Kehilas (Jewish Communities) of Johannesburg and the Witwatersrand – Jewish Communities of Johannesburg and those larger Rand towns and that fall outside the net of the great work being done by Beyachad in their Jewish Life in the South African Country Communities.

-From Eastern Europe to South Africa – a collection of family histories.

– English translations of the Keidan Yizkor book and The Rakishok Yizkor book.

-The Ochberg Orphans – Volume Two and My Inheritance – my family history – the stories of my four grandparents

Shalom, best wishes and good health to you all and may there soon be peace in Israel

David

David Solly Sandler sedsand@iinet.net.au

Compilations by David Solly Sandler

100 Years of Arc Memories published 2006

The Arcadia Centenary book contains the memories of over 120 children of The South African Jewish Orphanage.

More Arc Memories published 2008

A follow-up of the Centenary book with the memories of more than 100 children. This book includes a section of 17 chapters on the Ochberg Orphans.

The Ochberg Orphans and the Horrors From Whence They Came published 2011

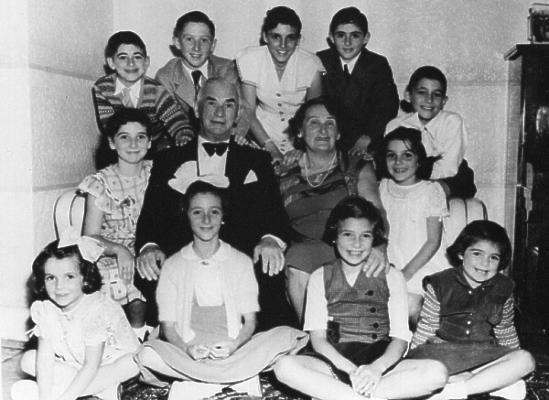

The rescue in 1921 of 181 Ukrainian War and Pogrom Orphans by Isaac Ochberg, the representative of the South African Jewish Community, from the horrors of the Pale of Settlement.

The Pinsker Orphans published 2013

The Pinsker Orphans book – in part a follow up of The Ochberg Orphans book – tells of the life and times of the children from the three Pinsk Jewish Orphanages in the 1920s and like The Ochberg Orphans book is but a small part of a much larger and forgotten part of Jewish History, the horrors suffered by the Jews in The Pale of Settlement between the two world wars.

This Was a Man Reprinted 2014

This book is the life story of Isaac Ochberg as written by his daughter Bertha Epstein and first published in 1974.

Reprinted with the permission of the family of Isaac Ochberg z”l with an addendum added.

Memories of Oranjia, The Cape Jewish Orphanage (1911-2011) published 2014

The book is a collection of the memories of many generations of children (over 120) who were in the care of The Cape Jewish Orphanage which was established in 1911 in Cape Town South Africa.

The Memorial Section of the Rakishok Memorial Book

This book was originally published in 1952 in Yiddish by the Rakishok Landmanschaft in Johannesburg. The book has been translated into English by Bella Golubchik and is for sale with all proceeds going to Arcadia Oranjia and the JDC.

Our Litvak Inheritance published 2016

This book tells of Jewish history, life and times in Lithuania and surrounds – the inheritance of most South African Jews and is the matching volume to Our South African Jewish Inheritance.

Please contact me to order your book – David Solly Sandler sedsand@iinet.net.au

THE SECTIONS OF THE BOOK AND THEIR CONTENTS IN DETAIL

1 The early history of South Africa in the Western and Eastern Cape Province.

This section tells of the early history of South Africa from the first Europen settlement in the Western Cape of the Dutch followed by theEnglish and the spread to the Eastern Cape.

It tells of the expansion eastwards, the exploits of the 1820 Settlers, the clash and 100 year war with the Xhosas (Bantu) and the Great Trek.

It relates the Jewish history during the periods of the Jewish Ministers in the Cape: The Rev. Isaac Pulver 1849-1851, The Rev. Joel Rabinowitz 1859-1882, The Rev. Abraham Frederick 1882-1894 and The Rev. Prof. Alfred Phillip Bender 1895-1894

2 Kimberley and the discovery of Diamonds (Northern Cape)

This section starts with the discovery of diamonds , the early history of Kimberley, and early Jewish Communal history

It tells of the amalgamation of the Kimberley Mines and about the important roles Jews played to bring this about.

It tells of the Jewish Pioneers of Kimberley and of Jewish Communal life

3 The Establishment of Natal, The OrangeFree State and The Transvaal Boer Republics

On the way to the the ‘Promised Land’, be it the highveld of the Transvaal or subtropical Natal, the Voortrekkers (pioneers) engaged in many violent confrontations with the Matabele, the Zulus and other Bantu tribes. At each major encounter, after an initial reverse, the tribes were subdued, their land taken by right of conquest and their people taken as labour.

In Natal the Voortrekkers established a short-lived republic, but, after its annexation by the British in 1843, many Voortrekkers trekked back over the Drakensberg on to the highveld, the lands between the Orange and Vaal Rivers and across the Vaal River.

In 1852 and 1854 the British granted independence to the trekkers in the Transvaal (‘country across the Vaal River’ that became the Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek) and in the Orange River Colony ( the Free State Republic)

The English, bankrupted by the Napoleonic Wars, could not afford to annex the states and the enmity between the English Colonial Government and the farmers (‘Boers’) continued.

Thus, the seeds for further conflict – this time between the Boers and the English – were sown. It needed the spark provided by the twin discoveries of gold and diamonds in 1886 and 1867 respectively – desparately needed by the bankrupt English Government.

Historical Dictionary of the British Empire.

4 The discovery of Gold in the Witwatersrand and the founding of Johannesburg

This section tells of the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand, the founding of Johannesburg, the early Jewish Pioneers and the formative days of Johannesburg Jewry. It includes details of the Randlords, Notable Jewish Personalities, the opening of the Park Synagogue by Paul Kruger and the Jamesion Raid.

5 The Anglo Boer War 1899-1902

This section discusses the phases of the Anglo Boer War: the scorched earth policy adopted by the British and the concentration camps they established in which over 26,000 Boer women and children perished from starvation and disease.

It tells of the Boer prisoners of war and The Treaty of Vereeniging followed by The Boer War in the Hebrew Press, Boerejode, Jews in the Boer Forces, The Russians and the Anglo-Boer War and the Jews on The British Side.

Next we tell of Jewish Refugees at the Cape during The Anglo-Boer War followed by Life in Pretoria and Johannesburg during and after the Boer War and we have the life story of Samuel Marks, Pretoria’s most prominent Jew.

We end with the Union of South Africa in 1910

6 Immigration, Yiddish, Zionism and Jewish Culture

In this section we pause, step back and revisit our South African Jewish Inheritance from different perspectives.

We start off with Jewish Immigration and the struggle to get Yiddish accepted as a European Language.

It tells of the birth of Zionism and Jewish Culture in South Africa and the culture clash between the English and Litvak (Eastern European or Russian) Jews.

We end with the Traditions of South African Litvak Jews

(In the next section are details of The South African Jewish Congress that gained the support of Jan Christiaan Smutsthe SA Boer leader who shared in the creation of Israel. )

7 World War One

This section tells of World War One (The Great War) first from a global and then a South African perspective.

It tells of the horrors of the war in ‘The Pale of Settlement’ (Eastern Europe) and the help given by the South African Jews to their bretheren in the Pale and in Palestine

Then we have details of The South African Jewish Congress seeking and gaining the support of Jan Christiaan Smuts the Boer who shared in the creation of Israel

We end with the The Spanish Influenza Pandemic 1918-1919

8 The Generosity of the S A Jewish Community

“This may help to explain how South African Jewry has acquired the characteristics which distinguish it as a group. It has a world-wide reputation for liberality towards those of its co-religionists who are in need, and for staunch support of the Zionist movement. It is also recognised as a well-organised and relatively united community.

Being largely descendants of Lithuanian Jewry, South African Jews are a fairly homogeneous group, unlike those of the United States of America. They have inherited some of the qualities of the Litvaks – their warm-heartedness and generosity, their practical-mindedness, a strong feeling of Jewish solidarity, and a love of learning combined with a somewhat critical attitude to religious traditions, their religion being often more of the head than of the heart.

Enterprising and hard-working, they have been able to take advantage of the opportunities offered by a new and developing country.”

Extract from THE JEWS IN SOUTH AFRICA Edited by Gustav Saron and Louis Hotz. Printed in 1955

The Generosity of the S A Jewish Community, Jewish Institutions, Funds and Appeals

This section starts with the early history of The Johannesburg Chevrah Kadisha, The South African Jewish Orphanage (Arcadia) and The Cape Jewish Orphanage (Oranjia), two institutions that still look after Jewish children in need today.

This is followed by three chapters of the good work done byThe United South African Jewish Relief, Reconstruction and Orphans Fund (1915-1925) that funded the rescuein 1921 of 181 Pogrom Orphans from the horrors of the Ukraine and Poland by Isaac Ochberg.

We end withThe 1930 Annual Report of the South African Jewish Orphanage with the names of thousands of supporters not only from Johannesburg but from many surrounding country areas.

9 Landsmanschaften Mutual Aid Societies

To help one another and the new immigrants arriving with virtually nothing Landsleit (people from the same towns or districts) banded together to form Landsmanschaften (Mutual Aid Societies) that helped the sick and poor, burried the dead and provided interest free loans to help members start businesses. They also provided a place where mainly men could gather and socialise.

In South Africa there were Landsmanschaften from numerous towns: Anykster ,Birzer ,Dwinsk, Keidan, Kelmer, Kovno, Krakinover, Kroze, K]

10 World War Two

This section first documents the rise of Anti-Semitism in the 1930s from news articles and from Worlds Apart

It details South Africa’s military contributions and casualtiesand lifeduring the war and tells about”up north”

It tells of the Jews in WWII and gives details of individuals who made the supreme sacrifice, individuals who served and life as a POW

This section ends with Victory Day and with the arrival of the news of the Holocaust

11 Jewish Life in Country Communities (1947 &1948)

In this sectionArthur Markowitz tells of Jewish Life in South African country communities in his Nationwide Survey of Jewish Communities published in The South African Jewish Times in 1947-8

He tells of the Jewish contribition to the developement of agriculture and industry in the towns throughout South Africa and highlights the special contributionsof some Jewish individuals.

From the very early days Jews lived in almost every country town in South Africa and they played a very important roles from the early development of these towns. Typically they were the traders and professionals,running the General Dealer Store (Algemeene Handelaar), the Hotel and bar and they were the Doctor and Lawyer and some were Farmers

12 Jewish Communities and Personalities

This section of the Jewish Communities and Personalities of Durban, Bloemfontein and Johannesburg, supplements Arthur Markowitz’s Nationwide Survey of South African Jewish country communities in section 10.

We commence with compilations on Durban and Bloemfontein the main cities of Natal and the Orange Free State. This is followed by compilations on three Johannesburg Jewish Communities: Rosettenville / La Rochelle, Fordsburg / Mayfair and Parktown.

In Parktown, a suburb of very large estates, we focus on the South African Jewish Orphanage (Arcadia) and remember individuals connected to Arcadia, not only for their contribution to Arcadia, but because of their contribution to the broader community. (These articles come from the two Arcadia Memory Books and The Ochberg Orphans by David Solly Sandler )

13 Support for Israel during the Israeli War of Independence (1948 – 1949)

This section tells of thesupport given to the newly created State of Israel in their fight for independence by the Jews in South Africa

The Zionist Federation in South Africa actively recruited those experienced and who had fought in WWII and sent them to Israel. They specifically recruited pilots and if fact had a flying school in Germiston.

There are extracts from South Africa’s 800 and the names of the 800 South Africans volunteers who fought in Israel’s War of Birth and we remember the 85 South Africanswho fell.

The section ends with details of some who fought and fell in defence of Israel

14 The Struggle from Apartheid to Multi-racial elections

This section commences with the history of Apartheid and is followed by the treason trials and details the resistance and events leading to multi-ratial elections.

This entire section is sourced from Worlds Apart by Colin Tatz, Peter Arnold and Gillian Heller, apart from ‘The facts about South African Jews in the Apartheid Era’ by Maurice Ostroff.

We end with details of White Emigration

Once again I feel honoured to be the compiler of this book that belongs to the Jewish Community and is a collection of articles, extracts of books and family histories kindly shared and entrusted to me by many people.

Thank you to the following that have shared their family histories, their articles and their books:

Andrew Cassel and Aryeh Shcherbakov, of the Keidan Association of Israel and the USA, for permission to use extracts of The Keidan Yizkor Book published in Hebrew in 1977

Colin Tatz, Peter Arnold and Gillian Heller, for sharing parts of their book Worlds Apart

Diane Wolfson for permission to use extracts of The Pretoria Jewish Community up to 1930 by Mrs Myrtle Todes, Mr Selwyn Zwick, Mrs Naomi Nowosenetz, Dr Rayme Rabinowitz, Mrs Avril Cohen, Mrs Jill Katz (editor), Mrs Mary Kropman and and Mr Ralph Lanesman.

Joe Woolf for sharing his family history From Shatt (Seta) to South Africa and parts of South Africa’s 800 The Story of South African Volunteers in Israel’s War of Birth Henry Katzew.

Louis Zalman Glick Touyz for sharing his article Traditions of South African Litvak Jews and other articles

Dave Sacks of the SAJBD for sharing his articles on the Boer War

Saul Issroff, London UK of South African Jewish Genealogy for sharing his article early South Africa Jewish History and Bloemfontein

Other books sourced

-Birth of a Community by Chief Rabbi professor Israel Abrahams

-The Fordsburg-Mayfair Hebrew Congregation 1893-1964 by Bernard Sachs

-The Jews in South Africa, Edited by Gustav Saron and Louis Hotz

-The Nationwide Survey of the South African Jewish Community By Arthur Markowitz

-The Vision Amazing by Marcia Gitlin

-The War Report by J E H Groble

Much thanks go to Bennie Penzik for helping with the editing of the book

Thank you to Michael Perry Kotzen, an Ex Arcadian actor and nonagenarian, from Sydney, the most prolific contributor of Arc Memories, who has helped willingly with the proofreading of this book.

A very great thanks goes to Antoinette Weber, my partner of the past 14 years, who gave very generously of her time and assisted with the typing and proofreading. I have once again tried to match the very high standard of formatting she set in the first volume.

Thanks must again go to two very close Arc ‘brothers’, David Kotzen and Dr Solly Farber who passed away in July 2002 a day apart. They both inspired and encouraged and helped me and set me on the path to compiling books. I sometimes feel that it is not by chance that I share with them my names David and Solly. I hope that David and Solly, as well as Doc and Ma and all Old Arcs who have ‘bunked over the hill’ enjoy this book from above.

As at the end of February 2016 over R1,150,000 had been raised for Arcadia and R60,000 for Oranjia from book sales. We still have many copies of the Arcadia Memory books, The Ochberg Orphans books and other books for sale with the full proceeds going to the charities that still continue to look after children. See the back of the book for details of books and charities and contact me please. You can pay for the books locally and have them delivered to friends overseas.

PG compilation still to come:

I invite all South Africans to share their family histories and photos for the following two books.

– Kehilas (Jewish Communities) of Johannesburg and the Witwatersrand – Jewish Communities of Johannesburg and those larger Rand towns and that fall outside the net of the great work being done by Beyachad in their Jewish Life in the South African Country Communities.

-From Eastern Europe to South Africa – a collection of family histories.

– English translations of the Keidan Yizkor book and The Rakishok Yizkor book.

-The Ochberg Orphans – Volume Two and My Inheritance – my family history – the stories of my four grandparents

Shalom, best wishes and good health to you all and may there soon be peace in Israel

David

David Solly Sandler sedsand@iinet.net.au