First Cousins Reunited

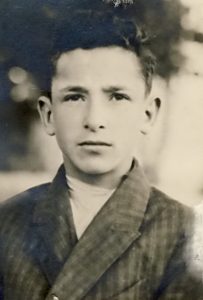

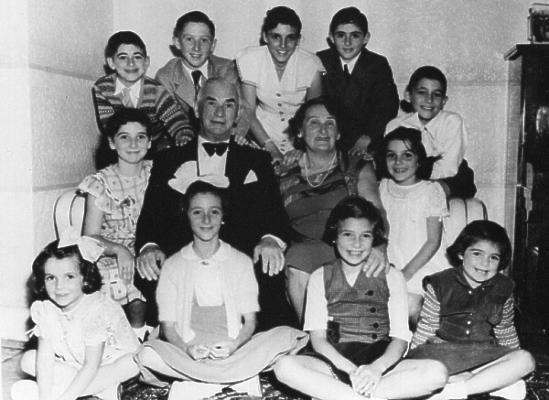

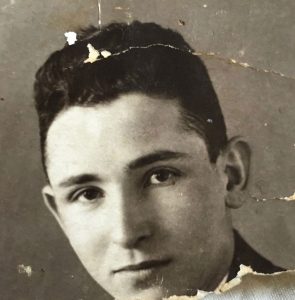

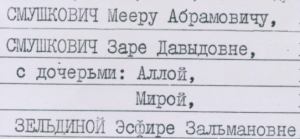

Finding My Cousin Zara Smushkovich

******************************************

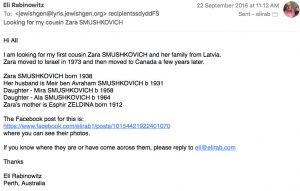

From

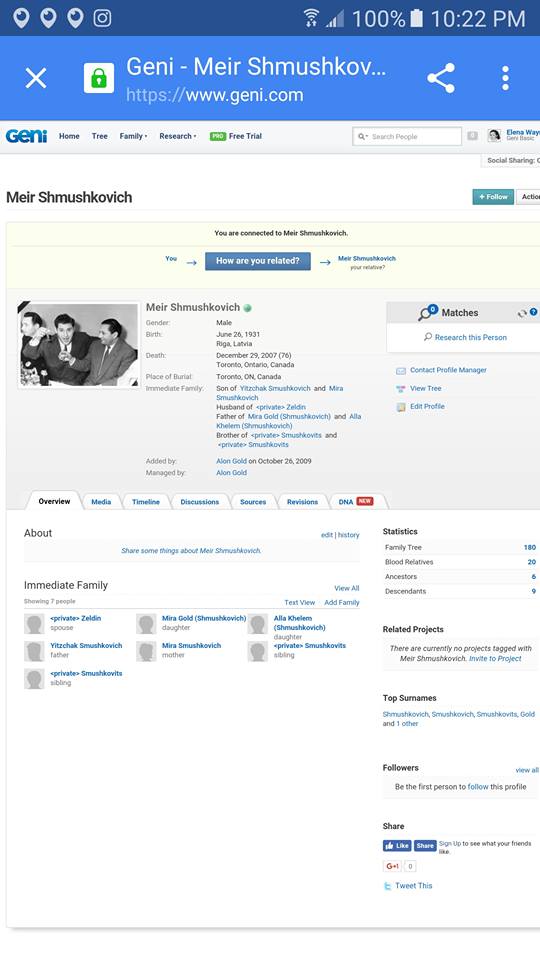

As many of you know I have been extremely immersed in the Genealogy of my family and Gary’s. I have been active in the genealogy community on Facebook. I had the pleasure of stumbling on a request from a very nice man in Australia looking for family members. I was able to very quickly find a record for one of his ancestors which helped him reconnect after decades! Today on the Jewish NEW YEAR I received a note and this link. At the end of this very wonderful family history I was honored to be mentioned. What a wonderful gift on Rosh Hashana! Eli Rabinowitz here is wishing many years of happiness with your newly found family. I am humbled to have been a small part of this wonderful Mitzvah.

L’Shana Tova.

Please check out this link to hear his story!

http://elirab.me/finding-my-cousin-zara-smushkovich/

Dear Eli

I am so glad that I could help you. Your blog was amazing. I wrote Bubble Segal many years ago and she answered me so I know her by correspondence. Again I am happy for you.

Wishing you and all your family a Healthy and Happy New Year.

Gert

Gert Rogers – Toronto – Searching Goldman Woda Sziiakovich from Mordy, Losice, and Miedzyrzec Podlaski and Solnik Djtelbaum from Staszow all in Poland

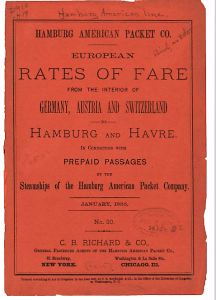

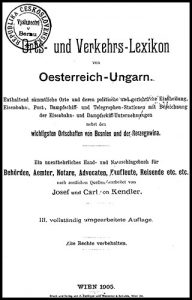

Useful Resources by Edward David Luft – A New Website

This website contains links to two separate databases. The first one is a listing of the third class railway fare from all of the train stations in Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Switzerland to le Havre and Hamburg when paid in U. S. dollars in New York or Chicago. The second database is a gazetteer of all of the locations in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1905.

Further resources will be added to this website from time to time.

To view, click on Useful Resources by Edward David Luft. The site is managed by Eli Rabinowitz

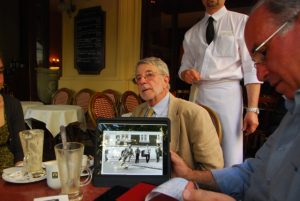

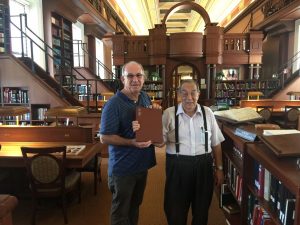

Eli and Edward David Luft at the Library Of Congress – August 2016.

We have been corresponding since October 2013 and met last month for the first time in Washington DC.

Let’s Catch Up At IAJGS In Seattle

Hi from Perth, Australia.

I start my long 24 hour trek early tomorrow from Perth to Seattle.

I will be in Seattle until Tuesday evening.

I am giving a presentation at a South African Tea Party this Saturday afternoon. This will be of interest to those wanting to connect with their shtetl.

This talk is being held within walking distance from the Sheraton.

For more details, see:

http://elirab.me/litvak-portal

I plan to spend most of Monday and Tuesday meeting up with the many people I have communicated with via the 70 JewishGen KehilaLinks I write and manage.

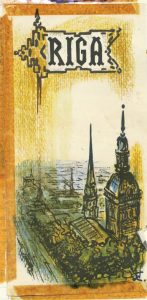

These Jewish websites cover many countries and regions – Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Germany, Belarus, Russia, South Africa, Australia and China.

The list is here:

http://elirab.me/litvak-portal/kehilalinks/

If you would like to catch up with me to discuss these, your shtetl, heritage travel or just to say hello, email me at eli@elirab.com. I am likely to be near the lobby.

See you soon!

Best regards

Eli Rabinowitz

Perth, Australia

eli@elirab.com

The Stropkover Rebbe and Me

The Stropkover Rebbe has just completed a visit to Perth Australia from Jerusalem.

We were honoured to have him spend Shabbat with us at the CHABAD shul in Noranda WA.

He has visited Perth before.

I took the opportunity on Saturday night to learn more about him and his town.

The Rebbe was born in Germany and lives in Jerusalem. The Stropkover Rebbe’s “once upon a time” community was based in Stropkov in Slovakia.

Stropkov

| Stropkov | ||

| Town | ||

|

View of Stropkov

|

||

|

||

| Country | Slovakia | |

|---|---|---|

| Region | Prešov | |

| District | Stropkov | |

| River | Ondava | |

| Elevation | 202 m (663 ft) | |

| Coordinates | 49°12′18″N 21°39′05″ECoordinates: 49°12′18″N 21°39′05″E | |

| Area | 24.667 km2 (9.524 sq mi) | |

| Population | 10,866 (2012-12-31) | |

| Density | 441 / km2 (1,142 / sq mi) | |

| First mentioned | 1404 | |

Stropkov (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈstropkow]; Hungarian: Sztropkó, pronounced [ˈstropkoː], Yiddish: סטראפקאוו) is a town in Stropkov District, Prešov Region, Slovakia.

Jewish community

Jews first arrived in Stropkov, possibly fleeing Polish pogroms, in about 1650. About fifty years later, the Jews were exiled from Stropkov to Tisinec, a village just to the north. They did not return to Stropkov until about 1800. The Stropkov Jewish cemetery was dedicated in 1892, after which the Tisinec cemetery fell into disuse.

In 1939 the antisemitic Hlinka Party gain control of the Stropkov Town Council. From May–October 1942 the Hlinka deported Jews from the Stropkov area to Auschwitz, Sobibor, Maidanek, and “unknown destinations”. By the end of World War II, only 100 Jews remained in Stropkov out of 2000 in 1942.

Chief Rabbis of Stropkov

The first rabbi of Tisinec and Stropkov was Rabbi Moshe Schonfeld. He left Stropkov for a position in Vranov. He was succeeded in 1833 by Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Teitelbaum (I)(1818–1883) who served as Stropkov’s chief rabbi until leaving for a post in Ujhely. The next incumbent was Rabbi Chaim Yosef Gottlieb (1790–1867), known as the “Stropkover Rov”. He was succeeded by Rabbi Yechezkel Shraga Halberstam (1811–1899), a son of Rabbi Chaim Halberstam of Sanz. His scholarship, piety, and personal charisma transformed Stropkov into one of the most respected chasidic centers in all Galicia and Hungary. Rabbi Moshe Yosef Teitelbaum (1842–1897), the son of the aforementioned Rabbi Yekusiel Yehuda Teitelbaum, was appointed as Stropkov’s next chief rabbi in 1880.

The charismatic and scholarly Rabbi Yitzhak Hersh Amsel (c1855–1934), the son of Peretz Amsel of Stropkov, was first appointed as a dayan in Stropkov and then as the rabbi of Zborov (near Bardejov). As legend has it, Rabbi Yitzhak Hersh Amsel died while praying in his Zborov synagogue. He is buried in the Stropkov cemetery where a small protective building ohel was erected over his grave to preserve it. Rabbi Amsel was succeeded in 1897 by Rabbi Avraham Shalom Halberstam (1856–1940). Jews, learned and simple alike, sought the advice and blessing of this “miracle rabbi of Stropkov”, revered as a living link in the chain of Chassidus of Sanz and Sienawa. Rabbi Halberstam served in Stropkov for some forty years, until the early 1930s, when he assumed a rabbinical post in the larger town of Košice. Rabbi Menachem Mendel Halberstam (1873–1954),the son of the aforementioned Rabbi Avraham Shalom Halberstam was then appointed chief rabbi of Stropkov and head of the Talmud Torah. After World War II Rabbi Menachem Mendel Halberstam lived in New York until the end of his life, teaching at the Stropkover Yeshiva, which he founded in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

The present day Admor of Stropkov is HaRav Avraham Shalom Halberstam of Jerusalem. The Admor runs several yeshivas and kolelim in Jerusalem and other cities in Israel. The Admor dedicates himself to Ahavat Yisrael and to helping many who need to return to their Jewish roots.

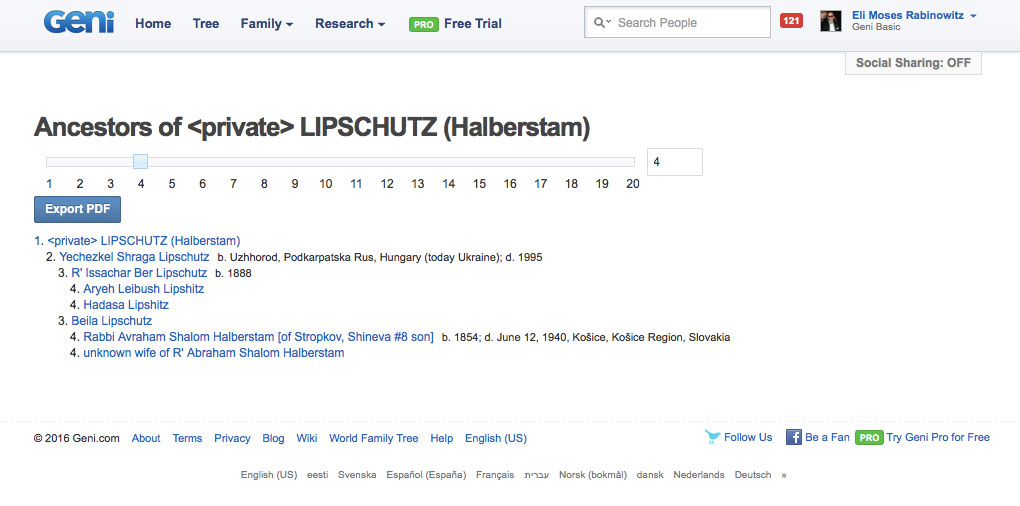

I then went into my Geni account and looked up the Stropkover Rebbe and found what appeared to be his family line.

I recalled that on Shabbat, he had been called up to the torah as HaRav Avraham Shalom ben Yechezkel Shrage.

Havdalah after Shabbat.

On Sunday I printed out this page on Geni and showed it to the Rebbe who confirmed that this was indeed him – i.e. Avraham Shalom Lipschutz (Halberstam). He also confirmed that his mother was Beila, daughter of Avraham Shalom Halberstam.

I also printed out the Geni page which shows our relationship and presented a copy to the Rebbe.

So, besides all the friends he has Downunder, he now is happy to have added a 8th cousin in this isolated Jewish community!

We are both members of the Katzenellenbogen Rabbinic Tree.

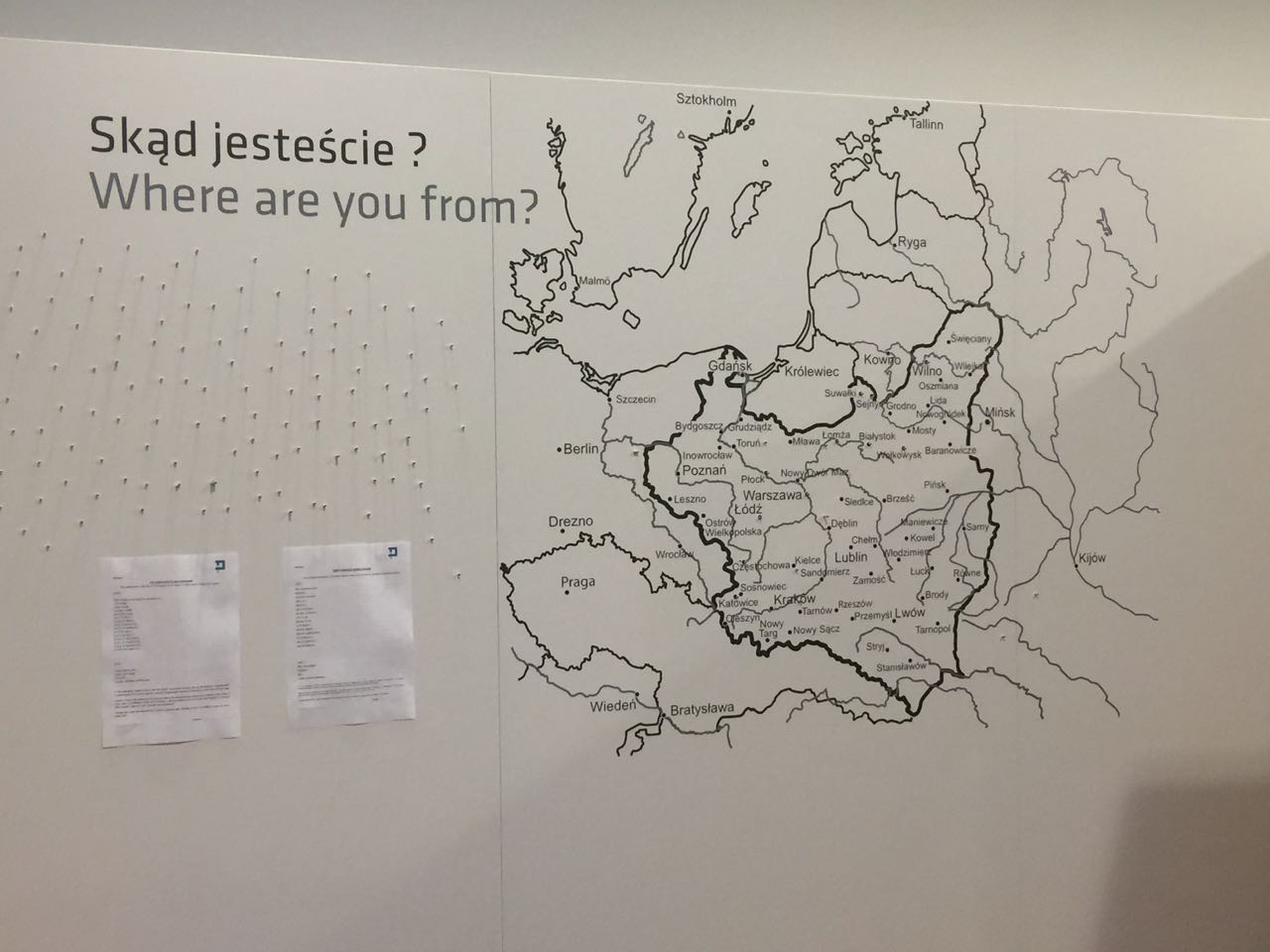

Warsaw, Poland

The Polin Museum

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

| Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich | |

The museum building

|

|

| Established | 2005 (opened April 2013) |

|---|---|

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Coordinates | 52°14′58″N 20°59′34″E |

| Type | Historical, cultural |

| Collection size | History and culture of Polish Jews |

| Visitors | expected 450,000 |

| Director | Dariusz Stola |

| Curator | Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett |

| Website | Museum official website |

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Polish: Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich) is a museum on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. The Hebrew word Polin in the museum’s name means, in English, either “Poland” or “rest here” and is related to a legend on the arrival of the first Jews in Poland.[1] The cornerstone was laid in 2007, and the museum was first opened on April 19, 2013.[2][3] The museum’s Core Exhibition opened in October 2014.[4] The museum features a multimedia narrative exhibition about the vibrant Jewish community that flourished in Poland for a thousand years up to the Holocaust.[5] The building, a postmodern structure in glass, copper, and concrete, was designed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma.[6

History

President of the Republic of Poland, Lech Kaczynski, at the groundbreaking ceremony for the POLIN Museum, 26 June 2007

The idea for creating a major new museum in Warsaw dedicated to the history of Polish Jews was initiated in 1995 by the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland.[7] In the same year, the Warsaw City Council allocated the land for this purpose in Muranów, Warsaw’s prewar Jewish neighborhood and site of the former Warsaw Ghetto, facing the Monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Heroes. In 2005, the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland established a unique private-public partnership with the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the City of Warsaw. The Museum’s first director was Jerzy Halbersztadt. In September 2006, a specially designed tent called Ohel (the Hebrew word for tent in English) was erected for exhibitions and events on the museum’s future location.[7]

An international architectural competition for designs for the building was launched in 2005, supported by a grant from the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. On June 30, 2005 the jury announced the winner; a team of two Finnish architects, Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma.[8] On June 30, 2009 construction of the building was officially inaugurated. The project was to be finished in 33 months at a cost of PLN 150 million zlotyallocated by the Ministry and the City.[9] and a total cost of PLN 320 million zloty.[10][11]

The museum opened the building and began its educational and cultural programs on April 19, 2013 on the 70th Anniversary of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. During the 18 months that followed, more than 180,000 visitors toured the building, visited the first temporary exhibitions, and took part in cultural and educational programs and events, including films, debates, workshops, performances, concerts and lectures. The Grand Opening, with the completed Core Exhibition, was on October 28, 2014.[12] The Core Exhibition documents and celebrates the thousand-year history of the Jewish community in Poland that was decimated by the Holocaust.[4][5]

In 2016 the museum won the European Museum of the Year Award from the European Museum Forum.[13]

The Jewish Historical Institute

Three videos from Matan Shefi, whom I bumped in the street, not far from Polin

Jewish Historical Institute

The Jewish Historical Institute (Polish: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny or ŻIH) is a research institute in Warsaw, Poland, primarily dealing with the history of Jews in Poland.

History

The Jewish Historical Institute was created in 1947 as a continuation of the Central Jewish Historical Commission, founded in 1944. The Jewish Historical Institute Association is the corporate body responsible for the building and the Institute’s holdings. The Institute falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. In 2009 it was named after Emanuel Ringelblum. The institute is a repository of documentary materials relating to the Jewish historical presence in Poland. It is also a centre for academic research, study and the dissemination of knowledge about the history and culture of Polish Jewry.

The most valuable part of the collection is the Warsaw Ghetto Archive, known as the Ringelblum Archive (collected by the Oyneg Shabbos). It contains about 6000 documents (about 30 000 individual pieces of paper).

Other important collections concerning World War II include testimonies (mainly of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust), memoirs and diaries, documentation of the Joint and Jewish Self-Help (welfare organizations active in Poland under the occupation), and documents from the Jewish Councils (Judenräte)

The section on the documentation of Jewish historical sites holds about 40 thousand photographs concerning Jewish life and culture in Poland.

The Institute has published a series of documents from the Ringelblum Archive, as well as numerous wartime memoirs and diaries.[1]

In 2011, Paweł Śpiewak, a Professor of Sociology at Warsaw University and former politician, was nominated as the Director of the Jewish Historical Institute by Bogdan Zdrojewski, Minister of Culture and National Heritage.[2]

The Nosyk Synagogue

Nożyk Synagogue

| Nożyk Synagogue Synagoga Nożyków |

|

|---|---|

| Basic information | |

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Geographic coordinates | 52°14′10″N 21°00′04″ECoordinates: 52°14′10″N 21°00′04″E |

| Affiliation | Orthodox Judaism |

| District | Śródmieście |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Active Synagogue |

| Leadership | Rabbi Michael Schudrich |

| Website | http://www.warszawa.jewish.org.pl |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Karol Kozłowski |

| Architectural style | neoromanesque |

| Completed | 1902 |

| Construction cost | 250.000 rubles |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 600 |

Interior of the synagogue

The Nożyk Synagogue (Polish: Synagoga Nożyków) is the only surviving prewar Jewish house of prayer in Warsaw, Poland. It was built in 1898-1902 and was restored after World War II. It is still operational and currently houses the Warsaw Jewish Commune, as well as other Jewish organizations.

History

Before World War II the Jewish community of Warsaw, one of the largest Jewish communities in the world at that time, had over 400 houses of prayer at its disposal. However, at the end of 19th century only two of them were separate structures, while the rest were smaller chapels attached to schools, hospitals or private homes. The earliest Round Synagogue in the borough of Praga served the local community since 1839, while the Great Synagogue (erected in 1878) was built for the reformed community. Soon afterwards a need arose to build a temple also for the orthodox Jewry. Between 1898 and 1902 Zalman Nożyk, a renowned Warsaw merchant, and his wife Ryfka financed such temple at Twarda street, next to the neighbourhood of Grzybów and Plac Grzybowski. The building was designed by a famous Warsaw architect, Karol Kozłowski, author of the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra Hall.[1] The façade is neo-romanticist, with notable neo-Byzantine elements. The building itself is rectangular, with the internal chamber divided into three aisles.

The synagogue was officially opened to the public on May 26, 1902. In 1914 the founders donated it to the Warsaw Jewish Commune, in exchange for yearly prayers in their intention. In 1923 the building was refurbished by Maurycy Grodzieński, who also designed a semi-circular choir that was attached to the eastern wall of the temple. In September 1939 the synagogue was damaged during an air raid. During World War II the area was part of the Small Ghetto and shared its fate during the Ghetto Uprising and then the liquidation of the Jewish community of Warsaw by the Nazis. After 1941 the Germans used the building as stables and a depot. After the war the demolished building was partially restored and returned to the Warsaw Jewish Commune, but the reconstruction did not start. It was completely rebuilt between 1977 and 1983 (officially opened April 18, 1983). It was also then that a new wing was added to the eastern wall, currently housing the seat of the commune, as well as several other Jewish organizations.

Ghetto Wall Marking

Meetings

Chopin and Kopernicus

The Storm

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Polish: Grób Nieznanego Żołnierza) is a monument in Warsaw, Poland, dedicated to the unknown soldiers who have given their lives for Poland. It is one of many such national tombs of unknowns that were erected after World War I, and the most important such monument in Poland.[1]

The monument, located at Piłsudski Square, is the only surviving part of the Saxon Palace that occupied the spot until World War II. Since 2 November 1925 the tomb houses an unidentified body of a young soldier who fell during the Defence of Lwów. At a later date earth from numerous battlefields where Polish soldiers have fought was added to the urns housed in the surviving pillars of the Saxon Palace.

The Tomb is constantly lit by an eternal flame and assisted by a guard post by the Representative Battalion of the Polish Army. It is there that most official military commemorations take place in Poland and where foreign representatives lay wreaths when visiting Poland.

The changing of the guard takes place on the hour of every hour daily and this happens 365 days a year.

History

In 1923, a group of unknown Varsovians placed, before Warsaw’s Saxon Palace and the adjacent Saxon Garden, a stone tablet commemorating all the unknown Polish soldiers who had fallen in World War I and the subsequent Polish-Soviet War. This initiative was taken up by several Warsaw newspapers and by General Władysław Sikorski. On April 4, 1925, the Polish Ministry of War selected a battlefield from which the ashes of an unknown soldier would be brought to Warsaw. Of some 40 battles, that for Lwów was chosen. In October 1925, at Lwów’s Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów, three coffins were exhumed: those of an unknown sergeant, corporal and private. The coffin that was to be transported to Warsaw was chosen by Jadwiga Zarugiewiczowa, mother of a soldier who had fallen at Zadwórze and whose body had never been found.

On November 2, 1925, the coffin was brought to Warsaw’s St. John’s Cathedral, where a Mass was held. Afterward eight recipients of the order of Virtuti Militari bore the coffin to its final resting place beneath the colonnade joining the two wings of the Saxon Palace. The coffin was buried along with 14 urns containing soil from as many battlegrounds, a Virtuti Militari medal, and a memorial tablet. Since then, except under German occupation during World War II, an honor guard has continuously been held before the Tomb.

Architecture

The Tomb was designed by the famous Polish sculptor, Stanisław Kazimierz Ostrowski. It was located within the arcade that linked the two symmetric wings of the Saxon Palace, then the seat of the Polish Ministry of War. The central tablet was ringed by 5 eternal flames and 4 stone tablets bearing the names and dates of battles in which Polish soldiers had fought during World War I and the Polish–Soviet War (1919–21). Behind the Tomb were two steel gratings bearing emblems of Poland’s two highest Polish military decorations — the Virtuti Militari and Cross of Valor.

During the 1939 invasion of Poland, the building was slightly damaged by German aerial bombing, but it was quickly rebuilt and seized by the German authorities. After the Warsaw Uprising, in December 1944, the palace was completely demolished by the Wehrmacht. Only part of the central colonnade, sheltering the Tomb, was preserved.

After the war, in late 1945, reconstruction began. Only a small part of the palace, containing the Tomb, was restored by Henryk Grunwald. On 8 May 1946 it was opened to the public. Soil from 24 additional battlegrounds was added to the urns, as well as more tablets with names of battles in which Poles had fought in World War II. However, the communist authorities erased all trace of the Polish–Soviet War of 1920, and only a few of the Polish Armed Forces’ battles in the West were included. This was corrected in 1990, after Poland had regained its political autonomy.

There are plans to rebuild the Saxon Palace, but as of May 2016, these plans have been indefinitely on hold due to a lack of budget.[citation needed]

The Hotel Bristol

Hotel Bristol, Warsaw

| Hotel Bristol, Warsaw | |

|---|---|

Hotel Bristol, Warsaw (2011)

|

|

| General information | |

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Address | Krakowskie Przedmiescie 42/44 |

| Opening | November 19, 1901 |

| Owner | Towarzystwo Akcyjne Budowy i Prowadzenia Hotelów, (1901-1928), Bank Cukrownictwa (1928-1948), City of Warsaw (1947-1952), Orbis (1952-1977), University of Warsaw (1977-1981), Orbis (1981-2011), Rosmarinum Investments (2011-) |

| Management | Starwood Hotels |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Władysław Marconi |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 168 |

| Number of suites | 38 |

| Website | |

| www.hotelbristolwarsaw.pl | |

Hotel Bristol, Warsaw is a historic luxury hotel opened in 1901 located on Krakowskie Przedmieście in Poland‘s capital, Warsaw

History

The Hotel Bristol was constructed from 1899-1900 on the site of the Tarnowski Palace by a company whose partners included Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski. A competition was held for the design of the building, and architects Thaddeus Stryjeriski and Franciszek Mączyński won with their Art Nouveau design. However the builders decided to change the style to a Neo-Renaissance design, and brought in architect Władysław Marconi to design the final hotel. Some of its interiors were designed by the noted Viennese architect Otto Wagner. The cornerstone was laid on April 22, 1899 and the hotel was dedicated on November 17, 1901 and opened on November 19, 1901.

Elegant cafe in the Bristol designed by Otto Wagner, 1901

After Poland gained its independence in 1919, Paderewski became the Prime Minister and held the first session of his government at his hotel. Paderewski and his partners sold their shares in the hotel in 1928 to a local bank, which renovated the hotel in 1934 with modern interiors by designer Antoni Jawornicki.

Upon the German invasion in 1939, the hotel was made into the headquarters of the Chief of the Warsaw District. It miraculously survived the war relatively unscathed, standing nearly alone among the rubble of its neighborhood. Following the war, the hotel was renovated and reopened in 1945.

The City of Warsaw took over operation of the hotel in 1947 and it was nationalized in 1948 and joined the state-run Orbis chain in 1952, exclusively serving visitors from abroad. By the 1970s its outdated facilities had seen it demoted to a second class ranking by the government and the hotel was donated by Prime Minister Peter Jaroszewicz to the University of Warsaw in 1977 to eventually serve as their library. It closed in 1981. However no work was done and the building languished through the waning days of the Communist government.

After the fall of Communism in 1989, the hotel was finally completely restored it to its former glory from 1991-1993, with the original interiors of the public rooms recreated to match the 1901 designs. The Bristol was reopened on April 17, 1993, with Margaret Thatcherin attendance, as part of the British Forte Hotels chain. From 1998 to 2013, the hotel was part of the Le Méridien hotel chain. The exterior was further restored in 2005, and the interior redecorated in 2013, after which the hotel joined The Luxury Collection division of Starwood Hotels.

Warsaw Uprising Youth Monument

Mały Powstaniec

| Mały Powstaniec | |

|

|

| Coordinates | 52°14′59″N 21°0′34″ECoordinates: 52°14′59″N 21°0′34″E |

|---|---|

| Location | Warsaw Old Town, Warsaw, Poland |

| Designer | Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz |

| Material | Bronze sculpture |

| Completion date | 1 October 1983 |

| Dedicated to | The child soldiers of the Warsaw Uprising |

Mały Powstaniec (the “Little Insurgent”) is a statue in commemoration of the child soldiers who fought and died during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. It is located on Podwale Street, next to the ramparts of Warsaw’s Old Town.

The statue is of a young boy wearing a helmet too large for his head and holding a submachine gun. It is reputed to be of a fighter who went by the pseudonym of “Antek”, and was killed on 8 August 1944 at the age of 13. The helmet and submachine gun are stylized after German equipment, which was captured during the uprising and used by the resistance fighters against the occupying forces.

Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz[1] created the design for the monument in 1946, which was later used to make smaller copies of its present state. The statue was unveiled on October 1, 1983 by Professor Jerzy Świderski – a cardiologist who was a courier for the resistance during the uprising (pseudonym: “Lubicz”) serving in the Gustaw regiment of the Armia Krajowa. Behind the statue is a plaque with the engraved words of “Warszawskie Dzieci” (“Warsaw Children”), a popular song from the period: “Warszawskie dzieci, pójdziemy w bój – za każdy kamień twój, stolico damy krew” (“We’re the children of Warsaw, going into battle – for every stone of yours, we will give our blood”).

More Warsaw

Warsaw at night

Return to Vilnius June 2016

History

The city expanded when a railroad connecting Vilnius with Liepāja was built in 1871. During the First World War, the city was occupied by the Germans in 1915, and it became the capital of an administrative unit for the first time. In 1919 the first train departed from Kaišiadorys to Radviliškis. When Trakai and the rest of the Vilnius Region became part of Poland, Kaišiadorys became the temporary capital of the Trakai Apskritis.

On August, 1941, the Jewish population of the town and surroundings was murdered in mass executions perpetrated by an Einsatzgruppen of Germans and Lithuanian nationalists.[1][2]Wikipedia

The Kaisiadorys KehilaLink. Click here

With Karina Simonson

Karina Simonson is doing her PhD on Eli Weinberg and Leon Levson, two Litvak photographers who moved to South Africa. More info on these two photographers:

http://www.ken-art.com/blog/post/41/african-photography-documentary-part-2

If anyone has more info on these two photographers, please comment.

Back at the Choral Synagogue

Along the Neris River at dusk

Neris

Neris (![]() pronunciation (help·info), Belarusian: Ві́лія Viliya, Polish: Wilia) is a river rising in Belarus. It flows through Vilnius (Lithuania) and becomes a tributary of the Neman River (Nemunas) at Kaunas (Lithuania). Its length is 510 km (320 mi).

pronunciation (help·info), Belarusian: Ві́лія Viliya, Polish: Wilia) is a river rising in Belarus. It flows through Vilnius (Lithuania) and becomes a tributary of the Neman River (Nemunas) at Kaunas (Lithuania). Its length is 510 km (320 mi).

For 276 km (171 mi)[1] the river runs through Belarus, where it is called Viliya, and 235 km (146 mi) runs through Lithuania, where it is called Neris.

The Neris connects two old Lithuanian capitals – Kernavė and Vilnius. Along its banks are burial places of the pagan Lithuanians. At 25 km (16 mi) from Vilnius are the old burial mounds of Karmazinai, with many mythological stones and a sacred oak.

Seduva Commemoration

On 8 Jul 2016, at 5:48 PM, Sergey Kanovich <sergey.kanovich@lostshtetl.com> wrote:

Dear Seduvians and their descendants,

75 years ago a wave of brutal murder in some places within weeks and in other within months wiped out Jewish communities which were building their future across Lithuania for over six centuries.

At the end of August 1941 Seduva Jewish Community was no more.

We kindly invite you to join us at the event which will commemorate Seduva Jewish Community. We will gather on 30th of August for Kaddisch at the 3 mass murder sites and old Seduva Jewish Cemetery.

Please share this information with people you might know who are connected to Seduva.

We kindly ask you to confirm your participation with Jonas Dovydaitis (jonas.dovydaitis@lostshtetl.com) so we could arrange for the transportation from Vilnius to Seduva and back. Your presence is important to all of us. We are there to “Never forget” and our message is clear – memory is stronger than death.

Details of the event are enclosed in attachment.

We are looking forward to welcome you at the event and our project www.lostshtetl.com

Wishing you all good shabboes.

Best regards,

Sergey Kanovich

Dear Seduvians and their descendants,

I would dearly like to be there for the memorial ceremony of the 75th anniversary of the massacre of the Jewish community of Shadova, but having just returned from Lithuania, including a visit to Seduva with Sergey and his team, I will not be able to make another visit this year.

This is a good opportunity to thank Sergey, Jonas, Milda, Saulas for their work and to thank Ivan and Edwin for their dedication. Seduva has become one of the very few former Shtelach where the Jews who once populated the towns are given recognition in a central place, rather than only in the cemetery or at the site of the massacres. It is so important that the lost Jews of Lita are remembered as an important and universal part of Lithuanian heritage in general and not as a separate, peripheral community matter. The Lost Shtetl project is a major step in that direction.

On the 30th of August I will recite Kaddish for the murdered Jews of Shadova in general and specifically for my great uncle and aunt, Tuvia and Chaya Lederman, and my cousins, Shlomo & Esther Lederman and their daughters Leia and Feiga; Mera (Lederman) & Leibe Fischer; Sonia (Lederman) & Pinchas Rabinovitch and their daughters Shulamit and Miriam.

יהיה זכרם ברוך

Yasher Koach,

Jon Seligman

Zur Hadassa, Israel

My previous post on Seduva

Kalvarija Gymnazija & Survivor Meiškė Segalis

The Kalvarija Gymnazija

The library and museum

The students with teachers – Daura & Arune – History & Giedre – English

The Turkish exchange students

Giedre talking about the visiting Turkish students

Video presentation by students – Meiškė Segalis

Meiškė Antanas Segalis- Miliauskas was born in about 1938 (original birth certificate is missing), his father Abraom-Povilas Segalis, who was born in 1920 ,was an artistic personality both a painter and an artist. He was a baptised Jew, his mother Adelė Balevičiūtė Segalienė Miliauskienė was a Lithuanian, she was a maiden and after the war a shop-assistant.

In summer 1941, father together with other Jews was taken to the stables. (It was built in the place where the boiler house is nowadays). Father was with son while mother was free. On the execution day, standing close to the ditch, father was ordered to give the son to the guard who later handed him to mother. At the shooting site (the beginning was on the hill, downside the military barracks, close to the old lime tree) there were three ditches as big as the area, later the corps were covered with something white ( most probably calx).

A rescued son was hidden at mother‘s friend Maryte Griciute home in Rugiu street in Marijampole. (The second house on the corner) She was a single woman looking after parents‘ farm.She was also Adele‘s peer and lived in the neighbourhood. A child lived quite freely and called her “Mom Maryte“, yet he was hidden from a public eye and till 1947 he was constantly taken to Kalvarija to stay at Virbickai or Malisauskai so that he could play with children. On December 15th, 1942, mother was deported to the labour camp in Sulihau, Germany.

On February 24 th, after liberating the camp, the mother came back home to Lithuania on foot, it took three months for her. Afterwards, she married, became Miliauskiene and changed her son‘s birth date and other documents. What is more, her son Antanas did not want to acknowledge her as a mother as it was very complicated for him to leave his care taker.

Meiškė Segalis’s documents

Meeting survivor Meiškė Segalis

Meiškė at the synagogues

Meiškė is looking for his family in Canada

Please contact me if you have any information about Meiškė’s family in Canada.

Here are my images from my trip last year: