My first visit to Rietavas, Lithuania.

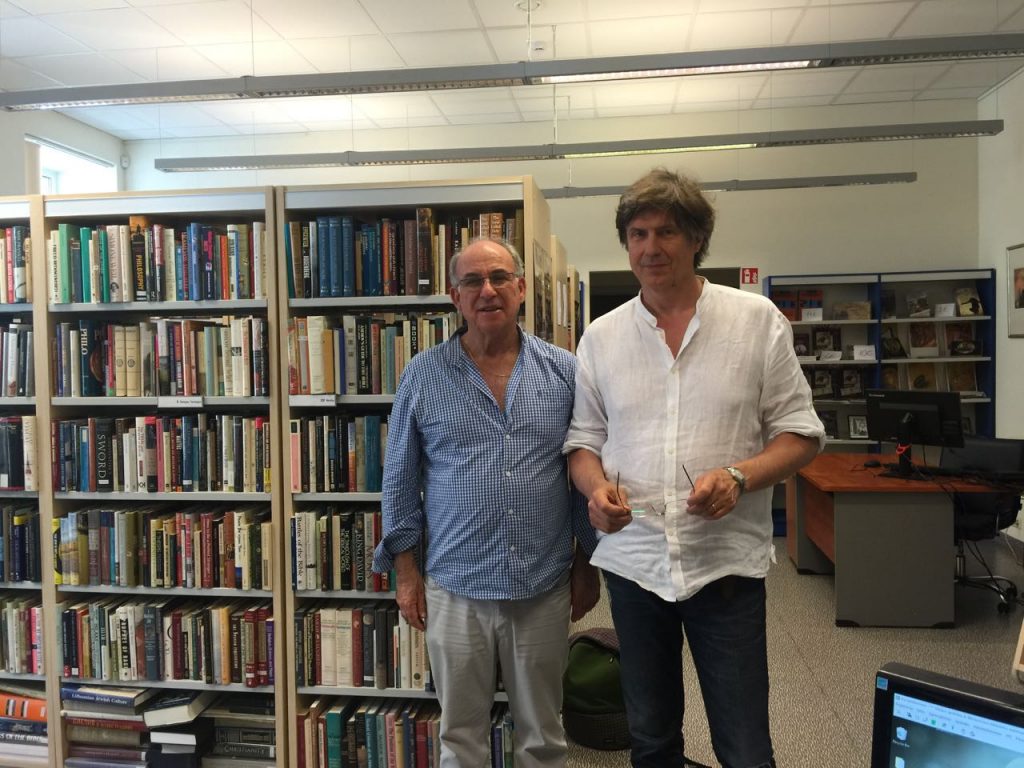

My lucky break was meeting Egidijus and Antonius at the Rietavas municipal offices.

They kindly showed me around the town.

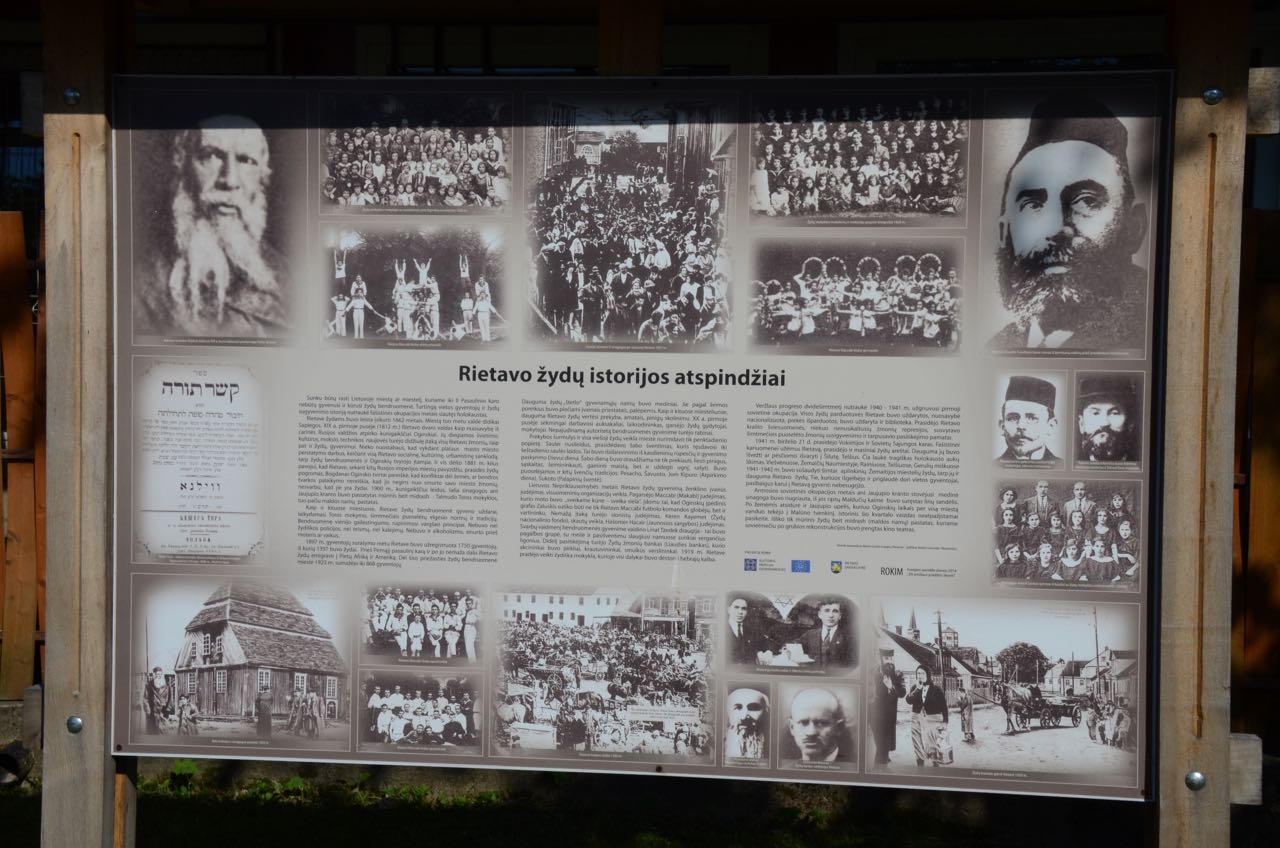

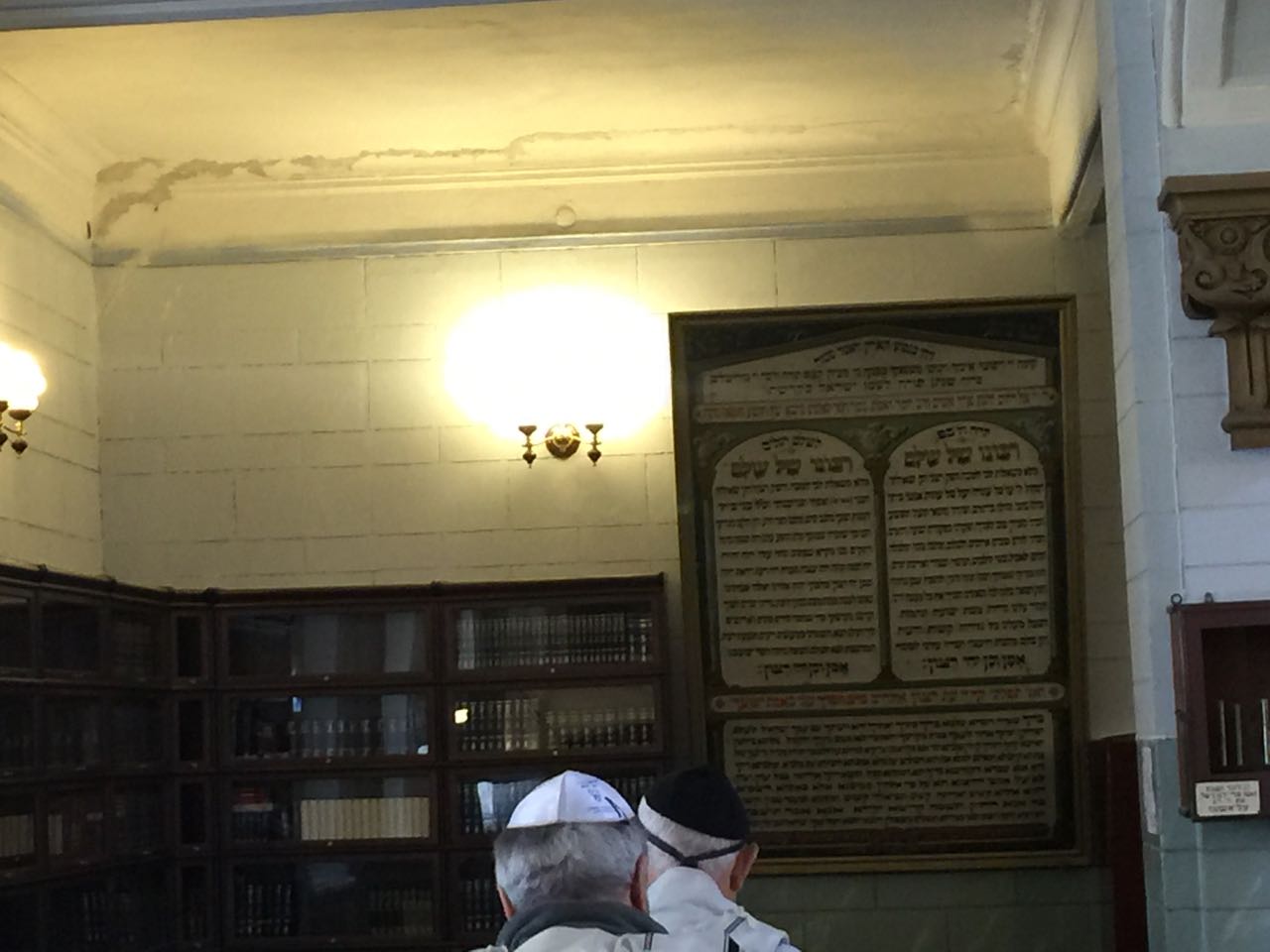

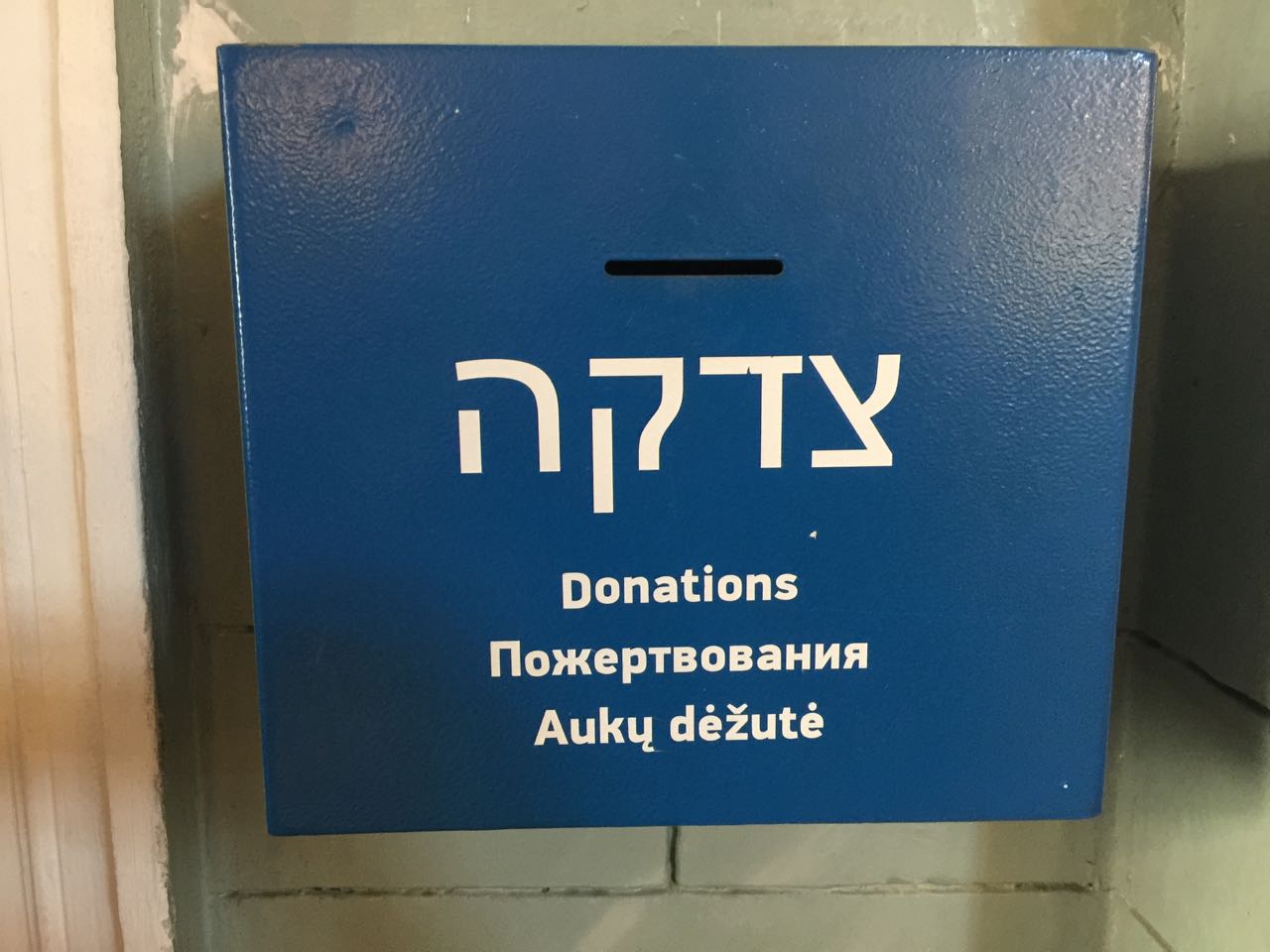

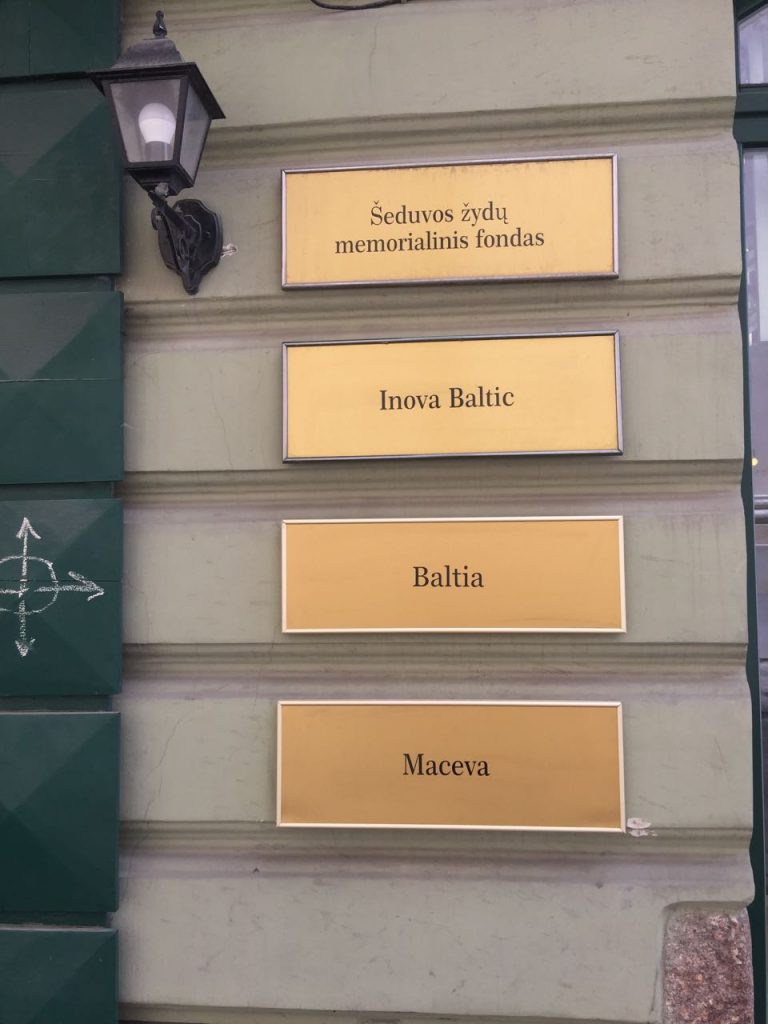

The former synagogue and memorial to Mendel Kaplan by the Jakovas Bunka Fund

A memorial Antonius arranged when he was mayor

The Jewish cemetery

Other images of Rietavas

Rietavas

| Rietavas | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

||

|

||

|

Rietavas

Location of Rietavas |

||

| Coordinates: 55°43′0″N 21°56′0″ECoordinates: 55°43′0″N 21°56′0″E | ||

| Country | ||

| Ethnographic region | Samogitia | |

| County | Telšiai County | |

| Municipality | Rietavas municipality | |

| Eldership | Rietavas city eldership | |

| Capital of | Rietavas municipality Rietavas city eldership Rietavas rural eldership |

|

| First mentioned | 1253 | |

| Granted city rights | 1792 | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 3,824 | |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | |

| Website | http://www.rietavas.lt | |

Rietavas (![]() pronunciation (help·info), Samogitian: Rėitavs) is a city in Lithuania on the Jūra River. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 3,979. It is the capital of Rietavas municipality.

pronunciation (help·info), Samogitian: Rėitavs) is a city in Lithuania on the Jūra River. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 3,979. It is the capital of Rietavas municipality.

The city is famous for building the first power station to produce electricity in Lithuania in 1892. The first telephone line in Lithuania was also built here.

History

Rietavas was first mentioned in written sources around 1253. During the Middle Ages it belonged to Ceklis land. Rietavas’ eldership was mentioned in 1527. Since 1533 Rietavas was known as a city however the city rights were not granted until 1792. In the 14th and 15th centuries Rietavas was one of the most important defence centres in Samogitia and also a crossing of commercial roads.

In the 19th century Rietavas was an important educational centre whereas in 1812–1909 it belonged to Ogiński family who loved culture and education. In 1835 there was established a hospital and four year later school of parish. In 1859 the school of agriculture was established in Rietavas which was closed in 1863. Lithuanian was the official language of this school (there were any other such schools where Lithuanian would be an official language at that time). In 1873 current Catholic Church reflecting features of Romanesque Revival architecture was built.

Rietavas also became an important centre of progressive technologios of that time. In 1882 the first telephone line in Lithuania was built. It connected Rietavas and Plungė cities. In 1892 started to produce electricity the first power station in Lithuania. On 17 April 1892 in Easter the first street lights were turned on in Rietavas manor, park and church.

In 1915 Rietavas was the centre of the county and later on centre of the eldership. During the Inter-war period there were established a public library in 1928, a cinema in 1931. After the World War II Rietavas became the centre of district municipality however in 1963 it was merged with Plungė district municipality. Nevertheless Rietavas retrieved its municipality in 2000.[1]

The coat of arms of Rietavas was approved by the decree of the President in 1996.[2]

Notable people

- Laurynas Ivinskis – Lithuanian teacher, publisher, translator and lexicographer.

- Diana Žiliūtė – Lithuanian racing cyclist, olympic medalist.

- Susman Brothers – businessmen in Rhodesia

The Cafe Riteve in Cape Town