POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Polish: Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich) is a museum on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. The Hebrew word Polin in the museum’s name means, in English, either “Poland” or “rest here” and is related to a legend on the arrival of the first Jews in Poland.[1] The cornerstone was laid in 2007, and the museum was first opened on April 19, 2013.[2][3] The museum’s Core Exhibition opened in October 2014.[4] The museum features a multimedia narrative exhibition about the vibrant Jewish community that flourished in Poland for a thousand years up to the Holocaust.[5] The building, a postmodern structure in glass, copper, and concrete, was designed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma.[6]

History

The idea for creating a major new museum in Warsaw dedicated to the history of Polish Jews was initiated in 1995 by the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland.[7] In the same year, the Warsaw City Council allocated the land for this purpose in Muranów, Warsaw’s prewar Jewish neighborhood and site of the former Warsaw Ghetto, facing the Monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Heroes. In 2005, the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland established a unique private-public partnership with the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the City of Warsaw. The Museum’s first director was Jerzy Halbersztadt. In September 2006, a specially designed tent called Ohel (the Hebrew word for tent in English) was erected for exhibitions and events on the museum’s future location.[7]

An international architectural competition for designs for the building was launched in 2005, supported by a grant from the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. On June 30, 2005 the jury announced the winner; a team of two Finnish architects, Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma.[8] On June 30, 2009 construction of the building was officially inaugurated. The project was to be finished in 33 months at a cost of PLN 150 million zlotyallocated by the Ministry and the City.[9] and a total cost of PLN 320 million zloty.[10][11]

The Museum opened the building and began its educational and cultural programs on April 19, 2013 on the 70th Anniversary of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. During the 18 months that followed, more than 180,000 visitors toured the building, visited the first temporary exhibitions, and took part in cultural and educational programs and events, including films, debates, workshops, performances, concerts and lectures. The Grand Opening, with the completed Core Exhibition, was on October 28, 2014.[12] The Core Exhibition documents and celebrates the thousand-year history of the Jewish community in Poland that was decimated by the Holocaust.[4][5]

Construction

The Museum faces the memorial commemorating the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943. The winner of the architectural competition was Rainer Mahlamäki, of the architectural studio ‘Lahdelma & Mahlamäki Oy in Helsinki, whose design was chosen from 100 submissions to the international architectural competition. The Polish firm Kuryłowicz & Associates was responsible for construction. The building’s minimalist exterior is clad with glass fins and copper mesh. Silk screened on the glass is the word Polin, in Latin and Hebrew letters.

The central feature of the building is its cavernous entrance hall. The main hall forms a high, undulating wall. The empty space is a symbol of cracks in the history of Polish Jews. Similar in shape to gorge, which could be a reference to the crossing of the Red Sea known from the Exodus. The museum is nearly 13,000 square meters of usable space. At the lowest level, in the basement of the building will be placed a main exhibition about history of Jews from the Middle Ages to modern times. The museum building also has a multipurpose auditorium with 480 seats, temporary exhibition rooms, education center, information center, play room for children, café, shop, and in the future kosher restaurant.

Hebrew and Latin letters of the word Polin

Since the museum presents the whole history of Jews in Poland, not only the period under German occupation, the designer wanted to avoid similarities to existing Holocaust museums (such as the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the museum at Yad Vashem) which had austere concrete structures. The architects kept the museum in the colors of sand, giving it a more approachable feeling.[13]

In 2008, the design of the museum was awarded the Chicago Athenaeum International Architecture Award.[14] In 2014, the designer Rainer Mahlamäki was awarded the Finlandia Prize for Architecture for his design of the museum.[15]

Organizational structure

The Core Exhibition’s academic team consists of Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (Program Director) of New York University, Hanna Zaremska of the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Adam Teller of Brown University, Igor Kąkolewski of the University of Warmia and Mazury, Marcin Wodziński of the University of Wrocław, Samuel Kassow of Trinity College, Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research at the Polish Academy of Sciences, Helena Datner of the Jewish Historical Institute, and Stanisław Krajewski of Warsaw University. Antony Polonsky of Brandeis University is the Core Exhibition’s chief historian.[16]

The North American Council of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews is a U.S. based non-profit organization supporting the foundation of the Museum.[17]

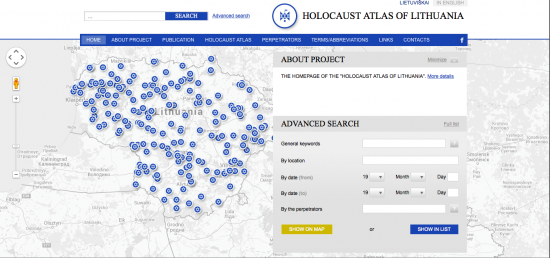

On June 17, 2009 the museum launched the Virtual Shtetl portal, which collects and provides access to essential information about Jewish life in Poland before and after the Holocaust in Poland. The portal now features more than 1,240 towns with maps, statistics, and image galleries based in large measure on material provided by local history enthusiasts and former residents of those places.[18]

Core Exhibition

The Core Exhibition occupies more than 4,000 m2 of space. It consists of eight galleries that document and celebrate the thousand-year history of the Jewish community in Poland – once the largest Jewish community in the world – that was almost entirely destroyed during the Holocaust. The exhibition includes a multimedia narrative with interactive installations, paintings and oral histories, among other features created by more than 120 scholars and curators. One item is a replica of the roof and ceiling of a 17th-century Gwoździec synagogue.[5][19] The galleries are:

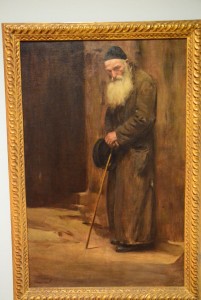

- Forest – This gallery tells the tale of how, fleeing from persecution in Western Europe, the Jews came to Poland. For the next 1,000 years, the country would become the largest European home for the Jewish community.

- First Encounters (the Middle Ages) – This gallery is devoted to the first Jewish settlers in Poland. Visitors meet Ibrahim ibn Jakub, a Jewish diplomat from Cordoba, author of famous notes from a trip to Europe. One of the most interesting objects presented in the gallery is the first sentence written in Yiddish in the prayer book of 1272.

Reconstructed vault and bimah in the Museum of the History of Polish Jews

- Paradisus Iudaeorum (15th and 16th centuries) – This gallery presents how the Jewish community was organized and what role Jews played in the country’s economy. One of the most important elements in this gallery is an interactive model of Kraków and Jewish Kazimierz, showing the rich culture of the local Jewish community. Visitors learn that religious tolerance in Poland made it a “Paradisus ludaeorum” (Jewish paradise). This golden age of the Jewish community in Poland ended with pogroms during the Khmelnitsky Uprising. This event is commemorated by a symbolic fire gall leading to the next gallery.

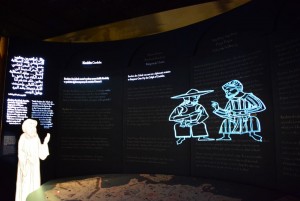

- The Jewish Town (17th and 18th centuries) – This gallery presents the history of Polish Jews until the period of the partitions. It is shown by an example of a typical borderland town where Jews constituted a significant part of the population. The most important part of this gallery is a unique reconstruction of the roof and ceiling of Gwoździec, a wooden synagogue that was located in the Ukraine.

“On the Jewish Street” gallery with entrances to exhibition halls

- Encounters with Modernity (19th century) – This gallery presents the time of the partitions when Jews shared the fate of Polish society divided between Austria, Prussia and Russia. The exhibition includes the role played by Jewish entrepreneurs, such as Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański, in the industrial revolution in Polish lands. Visitors also learn about changes in traditional Jewish rituals and other areas of life, and the emergence of new social movements, religious and political. This period is also marked by the emergence of modern anti-semitism, which Polish Jews had to face.

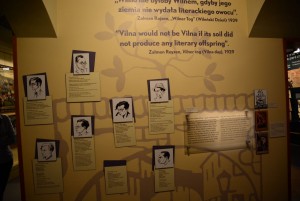

- On the Jewish Street – This gallery is devoted to the period of the Second Polish Republic, which is seen – despite the challenges that the young country had to face – as a second golden age in the history of Polish Jews. A graphical timeline is presented with the most important political events of the interwar period. The exhibition also highlights Jewish film, theatre and literature.

- Holocaust – This gallery shows the tragedy of the Holocaust during the German occupation of Poland, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 90% of the 3.3 million Polish Jews. Visitors are shown the history of the Warsaw Ghetto and introduced to Emanuel Ringelblum and Oneg Shabbat. The gallery also covers the horrors experienced by the non-Jewish majority population of Poland during World War II as well as their reactions and responses to the extermination of Jews.

- Postwar Years – The last gallery shows the period after 1945, when most of the survivors of the Holocaust emigrated, mostly because of the post-war takeover of Poland by the Soviets and the state sponsored anti-Semitic campaign in 1968 conducted by the communist authorities. An important date is the year 1989, marking the end of Soviet domination, followed by the revival of a small but dynamic Jewish community in Poland.

The exhibition was developed by an international team of scholars and museum professionals from Poland, the United States and Israel as well as the Museum’s curatorial team under the direction of Prof. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett.[19]

See also

Notes and references

- Jump up ^ “A 1000-Year History of Polish Jews” (PDF). POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- Jump up ^ “Kolejna budowa spóźniona. Czy jakaś powstanie na czas?”. Gazeta Wyborcza. April 2012.

- Jump up ^ “Little Left of Warsaw Ghetto 70 Years After Uprising”. Yahoo!7. April 17, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b “About the Museum”, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, accessed December 18, 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Associated Press (June 24, 2007), Poland’s new Jewish museum to mark community’s thousand-year history.

- Jump up ^ Polish, Jewish leaders break ground on landmark Jewish museum The Associated Press, June 26, 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b A.J. Goldmann, “Polish Museum Set To Open Spectacular Window on Jewish Past” The Jewish Daily Forward, April 01, 2013.

- Jump up ^ “Konkurs na projekt” [Contest for the design of the Museum]. Stołeczny Zarząd Rozbudowy Miasta.

- Jump up ^ The Association for the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland took responsibility for creating the Core Exhibition and raising the funds for it at a cost of about PLN 120 million zloty, Rozpoczęto budowę Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich. Mkidn.gov.pl.

- Jump up ^ http://www.sejm.gov.pl/Sejm7.nsf/biuletyn.xsp?skrnr=KSP-96

- Jump up ^ http://www.mkidn.gov.pl/media/docs/2013/20130416_mzhp.pdf

- Jump up ^ Znamy datę otwarcia wystawy Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich 22 January 2014

- Jump up ^ Museum of the History of Polish Jews by Lahdelma & Mahlamäki Dezeen Magazine, 3 October 2013.

- Jump up ^ International Architecture Awards: 2008 Winners The Chicago Athenaeum.

- Jump up ^ “Arkkitehtuurin ensimmäinen Finlandia-palkinto: Rainer Mahlamäen puolanjuutalaisen historian museo Varsovassa”. Helsingin Sanomat. 4 Nov 2014. Retrieved 5 Nov 2014.

- Jump up ^ Museum of the History of Polish Jews: About the museum at JewishMuseum.org.

- Jump up ^ The North American Council of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

- Jump up ^ “The Virtual Shtetl”

- ^ Jump up to: a b “Core Exhibition”, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, accessed December 18, 2014